1509

| Millennium: | 2nd millennium |

|---|---|

| Centuries: | |

| Decades: | |

| Years: |

| 1509 by topic |

|---|

| Arts and science |

| Leaders |

| Birth and death categories |

| Births – Deaths |

| Establishments and disestablishments categories |

| Establishments – Disestablishments |

| Works category |

| Gregorian calendar | 1509 MDIX |

| Ab urbe condita | 2262 |

| Armenian calendar | 958 ԹՎ ՋԾԸ |

| Assyrian calendar | 6259 |

| Balinese saka calendar | 1430–1431 |

| Bengali calendar | 916 |

| Berber calendar | 2459 |

| English Regnal year | 24 Hen. 7 – 1 Hen. 8 |

| Buddhist calendar | 2053 |

| Burmese calendar | 871 |

| Byzantine calendar | 7017–7018 |

| Chinese calendar | 戊辰年 (Earth Dragon) 4206 or 3999 — to — 己巳年 (Earth Snake) 4207 or 4000 |

| Coptic calendar | 1225–1226 |

| Discordian calendar | 2675 |

| Ethiopian calendar | 1501–1502 |

| Hebrew calendar | 5269–5270 |

| Hindu calendars | |

| - Vikram Samvat | 1565–1566 |

| - Shaka Samvat | 1430–1431 |

| - Kali Yuga | 4609–4610 |

| Holocene calendar | 11509 |

| Igbo calendar | 509–510 |

| Iranian calendar | 887–888 |

| Islamic calendar | 914–915 |

| Japanese calendar | Eishō 6 (永正6年) |

| Javanese calendar | 1426–1427 |

| Julian calendar | 1509 MDIX |

| Korean calendar | 3842 |

| Minguo calendar | 403 before ROC 民前403年 |

| Nanakshahi calendar | 41 |

| Thai solar calendar | 2051–2052 |

| Tibetan calendar | 阳土龙年 (male Earth-Dragon) 1635 or 1254 or 482 — to — 阴土蛇年 (female Earth-Snake) 1636 or 1255 or 483 |

Year 1509 (MDIX) was a common year starting on Monday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar.

Events[edit]

January–March[edit]

- January 21 – The Portuguese first arrive at the Seven Islands of Bombay and land at Mahim after capturing a barge of the Gujarat Sultanate in the Mahim Creek.[1]

- February 3 – Battle of Diu: The Portuguese defeat a coalition of Indians, Muslims and Italians.[2]

- March 18 – Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor, names Margaretha land guardians of the Habsburg Netherlands.[3]

April–June[edit]

- April 7 – The Kingdom of France declares war on the Republic of Venice.[4]

- April 15 – The French army under the command of Louis XII leaves Milan to invade Venetian territory. Part of the War of the League of Cambrai and the Italian Wars.[5]

- April 21 – Henry VIII becomes King of England on the death of his father, Henry VII.[6]

- April 27 – Pope Julius II places Venice under interdict and excommunication for refusing to cede part of Romagna to papal control.[7]

- May 2 – Juan Ponce de León obtains authorization to bring his family from Spain to his home in the Casa de Contratación in Caparra, Puerto Rico.[8]

- May 9

- The French army under the command of Louis XII crosses the Adda River at Cassano d'Adda.[5]

- The Venetians, encamped around the town of Treviglio, move south towards the Po River in search of better positions.[5]

- May 14 – Battle of Agnadello: French forces defeat the Venetians. The League of Cambrai occupies Venice's mainland territories.[5]

- June 11

- Henry VIII of England marries Catherine of Aragon.[9]

- Luca Pacioli's De divina proportione, concerning the golden ratio, is published in Venice, with illustrations by Leonardo da Vinci.[10]

- June 19 – Brasenose College, Oxford, is founded by a lawyer, Sir Richard Sutton, of Prestbury, Cheshire, and the Bishop of Lincoln, William Smyth.[11]

- June 24 – King Henry VIII of England and Queen Consort Catherine of Aragon are crowned.[12]

July–September[edit]

- July 17 – Venetian forces retake the city of Padua from French forces.[13]

- July 26 – Krishnadevaraya ascends the throne of the Vijayanagara Empire.[14]

- August 8 – Maximillian I of the Holy Roman Empire along with French allies begins a siege of Padua that would last for months to retake the city.[4]

- August 19 – Maximillian I orders all Jews within the Holy Roman Empire to destroy all books opposing Christianity.[15]

- September 10 – The Constantinople earthquake destroys 109 mosques and kills an estimated 10,000 people.[16]

- September 11 – Portuguese fidalgo Diogo Lopes de Sequeira becomes the first European to reach Malacca, having crossed the Gulf of Bengal.[17]

- September 27 – A violent storm ravages the Dutch coast, killing potentially thousands of people.[3]

October–December[edit]

- October 2 – The siege of Padua ends with Venetian victory, causing the retreat of HRE and French forces back to Tyrol and Milan. The Venetians soon recapture the city of Vicenza. [4]

- November 4 – Afonso de Albuquerque becomes the Viceroy of Portuguese India,[18] replacing Francisco de Almeida, who departs five days later from Diu.[19] Almeida never makes it home, getting killed along with his 64 men in a battle on March 1 with the local Khoekhoe people at South Africa's Cape of Good Hope.

- November 10 – Uriel von Gemmingen is assigned to secure others' opinions before continuing the Jewish book purge started on August 19th.[15]

- December 1 – Prince Le Oanh is installed as the new Emperor of Vietnam by a coup d'etat against his cousin, Emperor Le Uy Muc, and is enthroned at the age of 14 as Emperor Le Tuong Duc. Uy Muc is granted his request to be allowed to commit suicide rather than to be executed.

Date unknown[edit]

- Erasmus writes his most famous work, In Praise of Folly.[20]

- St Paul's School, London is founded by John Colet, Dean of St Paul's Cathedral.[21]

- Royal Grammar School, Guildford, England, is founded under the will of Robert Beckingham.[22]

- Queen Elizabeth's Grammar School, Blackburn, England, is founded as a grammar school for boys.[23]

- Georg Tannstetter is appointed by Maximilian I as the Professor of Astronomy at the University of Vienna.[24]

- Johannes Pfefferkorn writes his fourth and fifth pamphlets condemning the Jewish faith and people, Das Osterbuch and Der Judenfeind.[15]

- Basil Solomon becomes Syriac Orthodox Maphrian of the East.[25]

Births[edit]

- January 2 – Henry of Stolberg, German nobleman (d. 1572)[26]

- January 3 – Gian Girolamo Albani, Italian Catholic cardinal (d. 1591)[27]

- January 25 – Giovanni Morone, Italian Catholic cardinal (d. 1580)[28]

- February 2 – John of Leiden, Dutch Anabaptist leader (d. 1536)[29]

- February 10 – Vidus Vidius, Italian surgeon and anatomist (d. 1569)[30]

- March 25 – Girolamo Dandini, Italian Cardinal[31]

- March 27 – Wolrad II, Count of Waldeck-Eisenberg, German nobleman (d. 1578)[32][33]

- April 23 – Afonso of Portugal, Portuguese Roman Catholic cardinal (d. 1540)[34]

- July 4 – Magnus III of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, German Lutheran bishop of the Prince-Bishopric of Schwerin (d. 1550)[35]

- July 10 – John Calvin, French religious reformer (d. 1564)[36]

- July 25 – Philip II, Count of Nassau-Saarbrücken, German nobleman (d. 1554)[37]

- August 3 – Étienne Dolet, French scholar and printer (d. 1546)[38]

- August 7 – Joachim I, Prince of Anhalt-Dessau, German prince (d. 1561)[39]

- August 25 – Ippolito II d'Este, Italian cardinal and statesman (d. 1572)[40]

- October 20 – Arthur Stewart, Duke of Rothesay, Scottish prince (d. 1510)[41]

- November 4 – John, Duke of Münsterberg-Oels, Polish-German nobleman (d. 1565)[42]

Date unknown[edit]

- Anneke Esaiasdochter, Dutch Anabaptist (d. 1539)[43]

- Bernardino Telesio, Italian philosopher and natural scientist (d. 1588)[44]

- Élie Vinet, French humanist (d. 1587)[45]

- François de Scépeaux, French governor (d. 1571)[46]

- François Douaren, French jurist (d. 1559)[47]

- Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada, Spanish conquistador (d. 1579)[48]

- Guillaume Le Testu, French privateer (d. 1573)[49]

- John Erskine of Dun, Scottish religious reformer (d. 1591)[50]

- Naoe Kagetsuna, Japanese Clan Officer (d. 1577)[51]

- Stanisław Odrowąż, Polish nobleman (d. 1545)[52]

Deaths[edit]

- January – Adam Kraft, German sculptor and architect (b. circa 1460)[53]

- January 27 – John I, Count Palatine of Simmern, German nobleman (b. 1459)[54]

- March 14 – Giovanni Antonio Sangiorgio, Italian cardinal (b. unknown)[55]

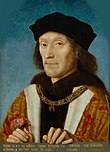

- April 21 – Henry VII of England, King of England and Lord of Ireland (b. 1457)[56]

- April 27 – Margaret of Brandenburg, German abbess of the Poor Clares monastery at Hof (b. 1453)[57]

- May 28 – Caterina Sforza, Italian countess of Forlì (b. 1463)[58]

- June 29 – Margaret Beaufort, Countess of Richmond and Derby, mother of Henry VII of England (b. 1443)[59]

- July 11 – William II, Landgrave of Hesse, German nobleman (b. 1469)[60]

- July 16

- Joao da Nova, Portuguese explorer (b. 1460)[61]

- Mikalojus Radvila the Old, Lithuanian nobleman (b. circa 1450)[62]

- July 28 – Ignatius Noah of Lebanon, Syriac Orthodox patriarch of Antioch (b. 1451).[63]

- December 1 – Lê Uy Mục, 8th king of the later Lê Dynasty of Vietnam (b. 1488)[64]

Date unknown[edit]

- Dmitry Ivanovich, Russian Grand Prince (b. 1483)[65]

- Eleanor de Poitiers, Burgundian courter and writer (b. circa 1444)[66]

- Hans Seyffer, German sculptor and woodcarver (b. circa 1460)[67]

- Shen Zhou, Chinese painter (b. 1427)[68]

- Viranarasimha Raya, Indian ruler of the Vijayanagar Empire (b. unknown)[69]

References[edit]

- ^ Greater Bombay District Gazetteer 1960, p. 163

- ^ Boletim Do Instituto Menezes Bragança. O Instituto. 1988. p. 62.

- ^ a b "1509 in History". brainyhistory.com. Retrieved March 29, 2022.

- ^ a b c J., Rickard. "War of the League of Cambrai, 1508-1510". historyofwar.org. Retrieved August 26, 2014.

- ^ a b c d Michael Mallett and Christine Shaw, The Italian Wars:1494–1559, (Pearson, 2012), 89.

- ^ Cheney, C. R.; Cheney, Christopher Robert; Jones, Michael (2000). A Handbook of Dates: For Students of British History. Cambridge University Press. pp. 37–38. ISBN 9780521778459.

- ^ "On April 27, 1509, Pope Julius II excommunicated the..." tribunedigital-chicagotribune. April 27, 2004. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- ^ Tió, Aurelio (1971). "La Primera Puertorriqueña (Boletín de la Academia Puertorriqueña de la Historia)" (PDF).

- ^ David Starkey (1991). Henry VIII: A European Court in England. Cross River Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-1-55859-241-4.

- ^ O'Connor, J J; Robertson, E F (July 1999). "Luca Pacioli". School of Mathematics and Statistics. University of St Andrews. Retrieved January 15, 2015.

- ^ "A History of Brasenose". bnc.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved March 23, 2022.

- ^ J.J. Scarisbrick, Henry VIII (1968) pp. 500–1.

- ^ Norwich, John Julius (1982). A History of Venice'. New York: Alfred B. Knopf. ISBN 9780394524108. Retrieved December 6, 2020.

- ^ Srinivasan, C. R. (1979). Kanchipuram Through the Ages. Agam Kala Prakashan. p. 200. OCLC 5834894. Retrieved July 25, 2014.[ISBN missing]

- ^ a b c "Johannes Pfefferkorn". Catholic Encyclopedia. 1913. Retrieved February 19, 2007.

- ^ Afyoncu, Erhan (July 28, 2020). "A glimpse of doom: Istanbul's earthquakes in history". Historian, Chancellor of the National Defense University of Ankara. Daily Sabah. Retrieved September 10, 2020.

- ^ Haywood, John (2002). Historical Atlas of the Early Modern World 1492–1783. Barnes & Noble Books. ISBN 0-7607-3204-3.

- ^ Stephens 1897, p. 1

- ^ Goodwin, A. J. H. (1952). "Jan van Riebeeck and the Hottentots 1652–1662". The South African Archaeological Bulletin. 7 (25): 2–6. doi:10.2307/3887530. ISSN 0038-1969. JSTOR 3887530.

- ^ Zweig, Stefan (1934). Erasmus And The Right To Heresy. pp. 51–52. Retrieved November 22, 2020.

- ^ "History and Archives". St Paul's School. Retrieved August 11, 2021.

- ^ "RGS Guildford History". rgsg.co.uk. Retrieved March 24, 2022.

- ^ "QEGS Blackburn History". qegsblackburn.com. Retrieved March 24, 2022.

- ^ Noflatscher, Heinz; Chisholm, Michael Andreas; Schnerb, Bertrand (2011). Maximilian I. (1459 - 1519): Wahrnehmung - Übersetzungen - Gender (in German). StudienVerlag. p. 245. ISBN 978-3-7065-4951-6. Retrieved March 28, 2022.

- ^ Wilmshurst, David (2019). "West Syrian patriarchs and maphrians". In Daniel King (ed.). The Syriac World. Routledge. p. 811.

- ^ Eduard Jacobs (1893), "Stolberg, Heinrich Graf zu", Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (in German), vol. 36, Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 335–339

- ^ Albani Giangirolamo Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine Civica Biblioteca Angelo Maj Bergamo

- ^ Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Leppäkari, Maria (2006). Apocalyptic Representations of Jerusalem. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-474-0878-9.

- ^ Bahşi, İlhan (2020). "Life of Guido Guidi (Vidus Vidius), who named the Vidian canal". Child's Nervous System. 36 (5): 881–884. doi:10.1007/s00381-018-3930-7. PMID 30066162. S2CID 51887276.

- ^ Francesco Antonio Zaccaria (1820). Episcoporum Forocorneliensium series (in Latin). Vol. Tomus II. Imola: Beneccius. pp. 178–180.

- ^ Haarmann, Torsten (2014). Das Haus Waldeck und Pyrmont. Mehr als 900 Jahre Gesamtgeschichte mit Stammfolge. Deutsche Fürstenhäuser (in German). Vol. Heft 35. Werl: Börde-Verlag. p. 48. ISBN 978-3-981-4458-2-4.

- ^ Hoffmeister, Jacob Christoph Carl (1883). Historisch-genealogisches Handbuch über alle Grafen und Fürsten von Waldeck und Pyrmont seit 1228 (in German). Cassel: Verlag Gustav Klaunig. p. 46.

- ^ The Cardinals of the Holy Roman Church

- ^ "Prince-Bishop/ Magnus III of Mecklenburg". ancestors.familysearch.org. Retrieved March 24, 2022.

- ^ Hubert Jedin; John Patrick Dolan (1993). The medieval and Reformation church. Crossroad. p. 588. ISBN 978-0-8245-1254-5.

- ^ "Philip II, Count of Nassau-Saarbrücken". memim.com. Retrieved March 25, 2022.

- ^ Powell, Alexandra A. "From Latin to French: Etienne Dolet (1509-1546) and the Rise of the Vernacular in Early Modern France". digitalrepository.trincoll.edu. Trinity College. Retrieved March 24, 2022.

- ^ "Joachim I, Prince of Anhalt-Dessau". www.britishmuseum.org. Retrieved March 24, 2022.

- ^ "The Cardinal Ippolito II d'Este", Tibersuperbum

- ^ "Arthur Stewart, Duke Of Rothesay". www.famechain.com. Retrieved March 24, 2022.

- ^ Handbuch der historischen Stätten: Schlesien. Stuttgart. 1977. pp. 322, 372, and 506. ISBN 3-520-31601-3. Retrieved March 25, 2022.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Esaiasdr., Anneke (ca. 1509-1539) (Dutch)". resources.huygens.knaw.nl. September 17, 2019. Retrieved March 24, 2022.

- ^ "Bernardino Telesio". plato.stanford.edu. Retrieved March 24, 2022.

- ^ Desgraves, Louis (1977). Élie Vinet, humaniste de Bordeaux, 1509-1587: vie, bibliographie, correspondance, bibliothèque. The University of Virginia: Droz. Retrieved March 23, 2022.

- ^ "Le panthéon de l'Anjou. François de Scépeaux, celui qui prônait la modération". ouest-france.fr. January 2, 2022. Retrieved March 23, 2022.

- ^ "Le Douaren, François". The Oxford Dictionary of the Renaissance. Oxford University Press. January 2005. ISBN 978-0-19-860175-3. Retrieved March 23, 2022.

- ^ "Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada (Spanish)". biografiasyvidas.com. Retrieved March 24, 2022.

- ^ Quinn, David B. Explorers and Colonies: America, 1500-1625. London: Hambleton Press, 1990. ISBN 1-85285-024-8

- ^ "Life of John Erskine, Baron of Dun". digital.nls.uk. National Library of Scotland. Retrieved March 24, 2022.

- ^ Kawanakajima 1553–64: Samurai power struggle Turnball, S. 2013.

- ^ "Stanisław Odrowąż ze Sprowy i Zagórza h. wł. (Polish)". www.sejm-wielki.pl. Retrieved March 24, 2022.

- ^ "Adam Krafft". newadvent.org. Retrieved March 24, 2022.

- ^ Winfried Dotzauer: Geschichte des Nahe-Hunsrück-Raumes von den Anfängen bis zur Französischen Revolution, Franz Steiner Verlag, 2001

- ^ From 1493; he was bishop of Frascati in 1503, bishop of Palestrina in 1507, bishop of Sabina in 1508.

- ^ R. L. Storey (1968). The Reign of Henry VII. Walker. p. 204.

- ^ von Minutoli, Julius (1850). Das kaiserliche Buch des Markgrafen Albrecht Achilles. Schneider. Retrieved March 25, 2022.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Palmieri, Anna; Iacoviello, Antoinette (2016–2017). "Caterina Sforza and Experimenti" (PDF). AMS Tesi di Laurea. Università di Bologna: 30. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 1, 2018. Retrieved June 18, 2019.

- ^ Carol M. Meale (December 12, 1996). Women and Literature in Britain, 1150-1500. Cambridge University Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-521-57620-8.

- ^ Marek, Miroslav. "Genealogy of the Hessian noble family". Genealogy.EU.

- ^ Albuquerque's Commentaries, vol. ii, p.49 online

- ^ "Facts about Mikolaj I: Radziwiłł family, as discussed in Radziwiłł family (Polish family)". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved February 15, 2010.

- ^ Barsoum, Aphrem (2003). The Scattered Pearls: A History of Syriac Literature and Sciences. Translated by Matti Moosa (2nd ed.). Gorgias Press. pp. 508–509. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- ^ "LÊ UY MỤC ĐẾ". nguoikesu.com. Retrieved March 24, 2022.

- ^ Bogatryrev (2007). Dmitry Ivanovich. p. 283.

- ^ "Aliénor de Poitiers". artandpopularculture.com. Retrieved March 24, 2022.

- ^ "Hans Seyffer". memim.com. Retrieved March 24, 2022.

- ^ "Shen Zhou". comuseum.com. March 8, 2015. Retrieved March 24, 2022.

- ^ Sen, Sailendra (2013). A Textbook of Medieval Indian History. Primus Books. pp. 108–109. ISBN 978-93-80607-34-4.

Sources[edit]

- Stephens, Henry Morse (1897). Albuquerque. Rulers of India series. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 978-81-206-1524-3.

- Greater Bombay District Gazetteer, Maharashtra State Gazetteers, vol. 27, Gazetteer Department (Government of Maharashtra), 1960, archived from the original on April 9, 2008, retrieved August 13, 2008