1907 Tiflis bank robbery

Erivansky Square, scene of the robbery, taken in the 1870s | |

| Date | 26 June 1907 |

|---|---|

| Time | 10:30 a.m. estimated |

| Location | Erivansky Square, Tiflis, Tiflis Governorate, Caucasus Viceroyalty, Russian Empire |

| Coordinates | 41°41′36″N 44°48′05″E / 41.6934°N 44.8015°E |

| Also known as | Erivansky Square expropriation |

| Organised by | |

| Participants |

|

| Outcome | 241,000 rubles (equivalent to US$341,050 in 2023) stolen |

| Deaths | 40 |

| Non-fatal injuries | 50 |

| Convictions | Conviction against Kamo in two separate trials |

The 1907 Tiflis bank robbery, also known as the Erivansky Square expropriation,[1] was an armed robbery on 26 June 1907[a] in the city of Tiflis (present-day Tbilisi, the capital of Georgia) in the Tiflis Governorate in the Caucasus Viceroyalty of the Russian Empire. A Bolshevik group "expropriated" a bank cash shipment to fund their revolutionary activities. The robbers attacked a bank stagecoach, and the surrounding police and soldiers, using bombs and guns while the stagecoach was transporting money through Erivansky Square (present-day Freedom Square) between the post office and the Tiflis branch of the State Bank of the Russian Empire. The attack killed forty people and injured fifty others, according to official archive documents. The robbers escaped with 241,000 rubles.[2]

The robbery was organized by a number of top-level Bolsheviks, including Vladimir Lenin, Joseph Stalin, Maxim Litvinov, Leonid Krasin, and Alexander Bogdanov; and executed by a party of revolutionaries led by Stalin's early associate Simon Ter-Petrosian, also known as "Kamo" and "The Caucasian Robin-Hood". Because such activities had been explicitly prohibited by the 5th Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) only weeks previously, the robbery and the killings caused outrage within the party against the Bolsheviks (a faction within the RSDLP). As a result, Lenin and Stalin tried to distance themselves from the robbery.

The events surrounding the incident and similar robberies split the Bolshevik leadership, with Lenin against Bogdanov and Krasin. Despite the success of the robbery and the large sum involved, the Bolsheviks could not use most of the large banknotes obtained from the robbery, because the police had records of the serial numbers. Lenin conceived a plan to have various individuals cash the large-value banknotes at once at various locations throughout Europe in January 1908, but this strategy failed, resulting in a number of arrests, worldwide publicity, and negative reaction from social democrats elsewhere in Europe.

Kamo was caught in Germany shortly after the robbery, but successfully avoided a criminal trial by feigning insanity for more than three years. He managed to escape from his psychiatric ward, but was recaptured two years later while planning another robbery. Kamo was then sentenced to death for his crimes including the 1907 robbery, but his sentence was commuted to life imprisonment; he was released after the 1917 Russian Revolution. None of the other major participants or organizers of the robbery were ever brought to trial. After Kamo's death in 1922, a monument to him was erected near Erivansky Square in Pushkin Gardens, and Kamo was buried beneath it. The monument was later removed and Kamo's remains were moved elsewhere.

Background[edit]

The Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP), the predecessor of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, was formed in 1898. The goal of the RSDLP was to carry out a Marxist proletarian revolution against the Russian Empire. As part of their revolutionary activity, the RSDLP and other revolutionary groups (such as anarchists and Socialist Revolutionaries) practised a range of militant operations, including "expropriations", a euphemism for armed robberies of government or private funds to support revolutionary activities.[3][4]

From 1903 onwards, the RSDLP were divided between two major groups: the Bolsheviks and the Mensheviks.[5] After the suppression of the 1905 Revolution, the RSDLP held its 5th Congress in May–June 1907 in London with the hopes of resolving differences between the Bolsheviks and the Mensheviks.[6][7] One issue that still separated the two groups was the divergence of their views on militant activities, and in particular, "expropriations".[7] The most militant Bolsheviks, led at the 5th Congress by Vladimir Lenin, supported continuation of the use of robberies, while Mensheviks advocated a more peaceful and gradual approach to revolution, and opposed militant operations. At the 5th Congress, a resolution was passed condemning participation in or assistance to all militant activity, including "expropriations" as "disorganizing and demoralizing", and called for all party militias to be disbanded.[6][7] This resolution passed with 65 per cent supporting and 6 per cent opposing (others abstained or did not vote) with all Mensheviks and some Bolsheviks supporting the resolution.[6]

Despite the unified party's prohibition on separate committees, during the 5th Congress the Bolsheviks elected their own governing body, called the Bolshevik Centre, and kept it secret from the rest of the RSDLP.[5][6] The Bolshevik Centre was headed by a "Finance Group" consisting of Lenin, Leonid Krasin and Alexander Bogdanov. Among other party activities, the Bolshevik leadership had already planned a number of "expropriations" in different parts of Russia by the time of the 5th Congress and was awaiting a major robbery in Tiflis, which occurred only weeks after the 5th Congress ended.[6][8][9]

Preparation[edit]

Before the 5th Congress met, high-ranking Bolsheviks held a meeting in Berlin in April 1907 to discuss staging a robbery to obtain funds to purchase arms. Attendees included Lenin, Stalin, Krasin, Bogdanov and Litvinov. The group decided that Stalin, then known by his earlier nom de guerre Koba,[b] and the Armenian Ter-Petrosian, known as Kamo, should organize a bank robbery in the city of Tiflis.[10]

The 29-year-old Stalin was living in Tiflis with his wife Ekaterina and newborn son Yakov.[11] Stalin was experienced at organizing robberies, and these exploits had helped him gain a reputation as the centre's principal financier.[1][5] Kamo, four years younger than Stalin, had a reputation for ruthlessness; later in his life he cut a man's heart from his chest.[12] At the time of the conspiracy, Kamo ran a criminal organization called "the Outfit".[13] Stalin said that Kamo was "a master of disguise",[12] and Lenin called Kamo his "Caucasian bandit".[12] Stalin and Kamo had grown up together, and Stalin had converted Kamo to Marxism.[12]

After the April meeting, Stalin and Litvinov travelled to Tiflis to inform Kamo of the plans and to organize the raid.[10][14] According to Roman Brackman's The Secret File of Joseph Stalin: A Hidden Life, while Stalin was working with the Bolsheviks to organize criminal activities, he was also acting as an informant for the Okhrana, the Russian secret police. Brackman alleges that once the group returned to Tiflis, Stalin informed his Okhrana contact, Officer Mukhtarov, about the bank robbery plans and promised to provide the Okhrana with more information at a later time.[10] However, Geoffrey Roberts has termed Brackman's allegation as a "conspiracy theory" and has further opined that all the evidence that Brackman adduces in support of this hypothesis is circumstantial and speculative.[15]

In Tiflis, Stalin began planning for the robbery.[10] He established contact with two individuals with inside information about the State Bank's operations: a bank clerk named Gigo Kasradze and an old school friend of Stalin's named Voznesensky who worked at the Tiflis banking mail office.[16][17] Voznesensky later stated that he had helped out in the theft out of admiration for Stalin's romantic poetry.[16][17] Voznesensky worked in the Tiflis banking mail office, giving him access to a secret schedule that showed the times that cash would be transferred by stagecoach to the Tiflis branch of the State Bank.[14] Voznesensky notified Stalin that the bank would be receiving a large shipment of money by horse-drawn carriage on 26 June 1907.[16][17]

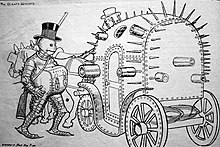

Krasin helped manufacture bombs to use in the attack on the stagecoach.[1] Kamo's gang smuggled bombs into Tiflis by hiding them inside a sofa.[18] Only weeks before the robbery, Kamo accidentally detonated one of Krasin's bombs while trying to set the fuse.[19] The blast severely injured him in the eye, leaving a permanent scar.[20][21] Kamo was confined to his bed for a month owing to intense pain, and had not fully recovered by the time of the robbery.[12][21]

Day of the robbery[edit]

On the day of the robbery, 26 June 1907, the 20 organizers, including Stalin, met near Erivansky Square (just 2 minutes from the seminary, bank and viceroy's palace) to finalize their plans, and after the meeting, they went to their designated places in preparation for the attack.[22] The Russian authorities had become aware that some large action was being planned by revolutionaries in Tiflis, and had increased the security presence in the main square; just prior to the robbery, they had been tipped off and were guarding every street corner in Erivansky Square.[13] To deal with the increased security, gang members spotted patrolling gendarmes and police prior to the robbery and lookouts were posted looking down on the square from above.[12][13]

The gang members mostly dressed themselves as peasants and waited on street corners with revolvers and grenades.[12] In contrast to the others, Kamo was disguised as a cavalry captain and came to the square in a horse-drawn phaeton, a type of open carriage.[12][23]

The conspirators took over the Tilipuchuri tavern facing the square in preparation for the robbery. A witness, David Sagirashvili, later stated that he had been walking in Erivansky Square when a friend named Bachua Kupriashvili, who later turned out to be one of the robbers, invited him into a tavern and asked him to stay. Once inside the tavern, Sagirashvili realized that armed men were stopping people from leaving. When they received a signal that the bank stagecoach was nearing the square, the armed men quickly left the building with pistols drawn.[12]

The Tiflis branch of the State Bank of the Russian Empire had arranged to transport funds between the post office and the State Bank by horse-drawn stagecoach.[24][25] Inside the stagecoach was the money, two guards with rifles, a bank cashier, and a bank accountant.[1][18][23] A phaeton filled with armed soldiers rode behind the stagecoach, and mounted cossacks[26] rode in front, next to, and behind the carriages.[18][23]

Attack[edit]

The stagecoach made its way through the crowded square at about 10:30 am. Kupriashvili gave the signal, and the robbers hit the carriage with grenades, killing many of the horses and guards, and began shooting security men guarding the stagecoach and the square.[1][18][27] Bombs were thrown from all directions.[18][28] The Georgian newspaper Isari reported: "No one could tell if the terrible shooting was the boom of cannons or explosion of bombs ... The sound caused panic everywhere ... almost across the whole city, people started running. Carriages and carts were galloping away".[18] The blasts were so strong that they knocked over nearby chimneys and broke every pane of glass for a mile around.[29][30] Ekaterina Svanidze, Stalin's wife, was standing on a balcony at their home near the square with her family and young child. When they heard the explosions, they rushed back into the house terrified.[29]

One of the injured horses harnessed to the bank stagecoach bolted, pulling the stagecoach with it, chased by Kupriashvili, Kamo, and another robber, Datiko Chibriashvili.[16][23][29] Kupriashvili threw a grenade that blew off the horse's legs, but he himself was caught in the explosion, landing stunned on the ground.[16] Kupriashvili regained consciousness and sneaked out of the square before police and military reinforcements arrived.[31] Chibriashvili snatched the sacks of money from the stagecoach while Kamo rode up firing his pistol,[16][23][32] and they and another robber threw the money into Kamo's phaeton.[32] Pressed for time, they inadvertently left twenty thousand rubles behind,[31] some of which was pocketed by one of the stagecoach drivers who was later arrested for the theft.[31]

Escape and aftermath[edit]

After securing the money, Kamo quickly rode out of the square; encountering a police carriage, he pretended to be a captain of the cavalry, shouting, "The money's safe. Run to the square."[32] The deputy in the carriage obeyed, realizing only later that he had been fooled by an escaping robber.[32] Kamo then rode to the gang's headquarters where he changed out of his uniform.[32] All of the robbers quickly scattered, and none were caught.[23][31]

One of the robbers, Eliso Lominadze, stole a teacher's uniform to disguise himself and came back to the square, gazing at the carnage.[31][33] Fifty casualties lay wounded in the square along with the dead people and horses.[23][28][33] The authorities stated that only three people had died, but documents in the Okhrana archives reveal that the true number was around forty.[33]

The State Bank was not sure how much it actually lost from the robbery, but the best estimates were around 341,000 rubles, worth around 3.4 million US dollars as of 2008.[23][33] About 91,000 rubles were in small untraceable bills, with the rest in large 500-ruble notes that were difficult to exchange because their serial numbers were known to the police.[23][33]

Stalin's role[edit]

Stalin's exact actions on the day of the robbery are unknown and disputed.[16] One source, P. A. Pavlenko, claimed that Stalin attacked the carriage itself and had been wounded by a bomb fragment.[16] Kamo later stated that Stalin took no active part in the robbery and had watched it from a distance.[23][32] Another source stated in a police report that Stalin "observed the ruthless bloodshed, smoking a cigarette, from the courtyard of a mansion."[32] Another source claims that Stalin was actually at the railway station during the robbery and not at the square.[32] Stalin's sister-in-law stated that Stalin came home the night of the robbery and told his family about its success.[33]

Stalin's role was later questioned by fellow revolutionaries Boris Nicolaevsky and Leon Trotsky. The latter, Stalin's rival, was later assassinated on orders from Stalin. In his book Stalin: An Appraisal of the Man and His Influence, Trotsky analyzed many publications describing the Tiflis expropriation and other Bolshevik militant activities of that time, and concluded, "Others did the fighting; Stalin supervised them from afar".[3] In general, according to Nicolaevsky, "The role played by Stalin in the activities of the Kamo group was subsequently exaggerated".[6] Kun later discovered official archive documents however clearly showing that "from late 1904 or early 1905 Stalin took part in drawing up plans for expropriations", adding, "It is now certain that [Stalin] controlled from the wings the initial plans of the group" that carried out the Tiflis robbery.[34]

Security response and investigation[edit]

The robbery featured in headlines worldwide: "Rain of Bombs: Revolutionaries Hurl Destruction among Large Crowds of People" in the London Daily Mirror, "Tiflis Bomb Outrage" in The Times of London, "Catastrophe!" in Le Temps in Paris, and "Bomb Kills Many; $170,000 Captured" in The New York Times.[23][28][31]

Authorities mobilized the army, closed roads, and surrounded the square hoping to secure the money and capture the criminals.[31] A special detective unit was brought in to lead the police investigation.[23][28][31] Unfortunately for the investigators, witness testimony was confusing and conflicting,[31] and the authorities did not know which group was responsible for the robbery. Polish socialists, Armenians, anarchists, Socialist-Revolutionaries, and even the Russian State itself were blamed.[31]

According to Brackman, several days after the robbery the Okhrana agent Mukhtarov questioned Stalin in a secret apartment. The agents had heard rumors that Stalin had been seen watching passively during the robbery. Mukhtarov asked Stalin why he had not informed them about it, and Stalin stated that he had provided adequate information to the authorities to prevent the theft. The questioning escalated into a heated argument; Mukhtarov hit Stalin in the face and had to be restrained by other Okhrana officers. After this incident, Mukhtarov was suspended from the Okhrana, and Stalin was ordered to leave Tiflis and go to Baku to await a decision in the case. Stalin left Baku with 20,000 rubles in stolen money in July 1907.[23] While Brackman claims to have found evidence of this incident, whether Stalin cooperated with the Okhrana during his early life has been a subject of debate among historians for many decades and has yet to be resolved.[35]

Moving the money and Kamo's arrest[edit]

The funds from the robbery were originally kept at the house of Stalin's friends in Tiflis, Mikha and Maro Bochoridze.[32] The money was sewn into a mattress so that it could be moved and stored easily without arousing suspicion.[36] The mattress was moved to another safe house, then later put on the director's couch at the Tiflis Meteorological Observatory,[23][33] possibly because Stalin had worked there.[23][33] Some sources claim that Stalin himself helped put the money in the observatory.[33] The director stated that he never knew that the stolen money had been stored under his roof.[33]

A large portion of the stolen money was eventually moved by Kamo, who took the money to Lenin in Finland, which was then part of the Russian Empire. Kamo spent the remaining summer months staying with Lenin at his dacha. That autumn, Kamo traveled to Paris, to Belgium to buy arms and ammunition, and to Bulgaria to buy 200 detonators.[20] He next traveled to Berlin and delivered a letter from Lenin to a prominent Bolshevik physician, Yakov Zhitomirsky, asking him to treat Kamo's eye, which had not completely healed from the bomb blast.[20] Unknown to Lenin, Zhitomirsky had been secretly working as an agent of the Russian government and quickly informed the Okhrana,[20] who asked the Berlin police to arrest Kamo.[20] When they did so, they found a forged Austrian passport and a suitcase with the detonators, which he was planning to use in another large bank robbery.[37]

Cashing the marked notes[edit]

After hearing of Kamo's arrest, Lenin feared that he too might be arrested and fled from Finland with his wife.[38] To avoid being followed, Lenin walked 5 km (3 mi) across a frozen lake at night to catch a steamer at a nearby island.[39] On his trek across the ice, Lenin and his two companions nearly drowned when the ice started to give way underneath them; Lenin later admitted it seemed like it would have been a "stupid way to die".[39] Lenin and his wife escaped and headed to Switzerland.[38][39]

The unmarked bills from the robbery were easy to exchange, but the serial numbers of the 500-ruble notes were known to the authorities, making them impossible to exchange in Russian banks.[23] By the end of 1907, Lenin decided to exchange the remaining 500-ruble notes abroad.[38] Krasin had his forger try to change some of the serial numbers.[40] Two hundred of these notes were transported abroad by Martyn Lyadov (they were sewn into his vest by the wives of Lenin and Bogdanov at Lenin's headquarters in Kuokkala).[6] Lenin's plan was to have various individuals exchange the stolen 500-ruble notes simultaneously at a number of banks throughout Europe.[38] Zhitomirsky heard of the plan and reported it to the Okhrana,[38] who contacted police departments throughout Europe asking them to arrest anyone who tried to cash the notes.[38]

In January 1908, a number of individuals were arrested while attempting to exchange the notes.[41][42][43] The New York Times reported that one woman who had tried to cash a marked 500-ruble note later tried to swallow evidence of her plans to meet her accomplices after the police were summoned, but the police stopped her from swallowing the paper by grabbing her throat, retrieved the paper, and later arrested her accomplices at the train station.[43] Most prominent among those arrested was Maxim Litvinov, caught while boarding a train with his mistress at Paris's Gare du Nord with twelve of the 500-ruble notes he intended to cash in London.[44][45] The French Minister of Justice expelled Litvinov and his mistress from French territory, outraging the Russian government, which had requested his extradition.[44] Officially the French government stated that Russia's request for extradition had been submitted too late, but by some accounts, they denied the extradition because French socialists had applied political pressure to secure his release.[44]

Nadezhda Krupskaya, Lenin's wife, discussed these events in her memoirs:

The money obtained in the Tiflis raid was handed over to the Bolsheviks for revolutionary purposes. But the money could not be used. It was all in 500-ruble notes, which had to be changed. This could not be done in Russia, as the banks always had lists of the note numbers in such cases ...The money was badly needed. And so a group of comrades made an attempt to change the 500-ruble notes simultaneously in various towns abroad, just a few days after our arrival ... Zhitomirsky had warned the police about the attempt to change the ruble notes, and those involved in it were arrested. A member of the Zurich group, a Lett, was arrested in Stockholm, and Olga Ravich, a member of the Geneva group, who had recently returned from Russia, was arrested in Munich with Bogdassarian and Khojamirian. Nikolai Semashko was arrested in Geneva after a postcard addressed to one of the arrested men was delivered to his house.[46]

Brackman claims that despite the arrests, Lenin continued his attempts to exchange the 500-ruble notes and did manage to trade some of them for 10,000 rubles from an unknown woman in Moscow.[42] According to Nicolaevsky, however, Lenin abandoned attempts to exchange the notes after the arrests,[6] but Bogdanov tried (and failed) to exchange some notes in North America, while Krasin succeeded in forging new serial numbers and managed to exchange several more notes.[6] Soon after, Lenin's associates burned all the 500-ruble notes remaining in their possession.[6][47]

Trials of Kamo[edit]

[R]esigned to death, absolutely calm. On my grave there should already be grass growing six feet high. One can't escape death forever. One must die some day. But I will try my luck again. Try any way of escape. Perhaps we shall once more have the laugh over our enemies ... I am in irons. Do what you like. I am ready for anything.

— Note from Kamo to a fellow prisoner in 1912 while awaiting the death penalty.[48]

After Kamo was arrested in Berlin and awaiting trial, he received a note from Krasin through his lawyer Oscar Kohn telling him to feign insanity so that he would be declared unfit to stand trial.[49] To demonstrate his insanity, he refused food, tore his clothes, tore out his hair, attempted to hang himself, slashed his wrists, and ate his own excrement.[50][51][52] To make sure that he was not faking his condition, German doctors stuck pins under his nails, struck him in the back with a long needle, and burned him with hot irons, but he did not break his act.[51][53] After all of these tests, the chief doctor of the Berlin asylum wrote in June 1909 that "there is no foundation to the belief that [Kamo] is feigning insanity. He is without doubt mentally ill, is incapable of appearing before a court, or of serving sentence. It is extremely doubtful that he can completely recover."[54]

In 1909 Kamo was extradited to a Russian prison, where he continued to feign insanity.[41][55] In April 1910, he was put on trial for his role in the Tiflis robbery,[56] where he ignored the proceedings and openly fed a pet bird that he had hidden in his shirt.[56] The trial was suspended while officials determined his sanity.[56][57] The court eventually found that he had been sane when he committed the Tiflis robbery, but was presently mentally ill and should be confined until he recovered.[58] In August 1911, after feigning insanity for more than three years, Kamo escaped from the psychiatric ward of a prison in Tiflis by sawing through his window bars and climbing down a homemade rope.[41][55][59]

Kamo later discussed these experiences:

What can I tell you? They threw me about, hit me over the legs and the like. One of the men forced me to look into the mirror. There I saw−not the reflection of myself, but rather of some thin, ape-like man, gruesome and horrible looking, grinding his teeth. I thought to myself, "Maybe I've really gone mad!" It was a terrible moment, but I regained my bearings and spat upon the mirror. You know I think they liked that ... I thought a great deal: "Will I survive or will I really go mad?" That was not good. I did not have faith in myself, see? ... [The authorities], of course, know their business, their science. But they do not know the Caucasians. Maybe every Caucasian is insane, as far as they are concerned. Well, who will drive whom mad? Nothing developed. They stuck to their guns and I to mine. In Tiflis, they didn't torture me. Apparently they thought that the Germans can make no mistakes.[60]

After escaping, Kamo met up with Lenin in Paris,[47] and was distressed to hear that a "rupture had occurred"[47] between Lenin, Bogdanov, and Krasin.[47] Kamo told Lenin about his arrest and how he had simulated insanity while in prison.[47] After leaving Paris, Kamo eventually met up with Krasin and planned another armed robbery.[41] Kamo was caught before the robbery took place and was put on trial in Tiflis in 1913 for his exploits including the Tiflis bank robbery.[48][41][61] This time, Kamo did not feign insanity while imprisoned, but he did pretend that he had forgotten all that happened to him when he was previously "insane".[61] The trial was brief and Kamo was given four death sentences.[62]

Seemingly doomed to death, Kamo then had the good luck along with other prisoners to have his sentence commuted to a long prison term as part of the celebrations of the Romanov dynasty tricentennial in 1913.[41][63] Kamo was released from prison after the February Revolution in 1917.[41][64]

Aftermath[edit]

Effect on Bolsheviks[edit]

Apart from Kamo, none of the organizers of the robbery were ever brought to trial,[65] and initially it was not clear who was behind the raid, but after the arrest of Kamo, Litvinov and others, the Bolshevik involvement became obvious.[6] The Mensheviks felt betrayed and angry; the robbery proved that the Bolshevik Centre operated independently from the unified Central Committee and was taking actions explicitly prohibited by the party congress.[6] The leader of the Mensheviks, Georgi Plekhanov, called for separation from the Bolsheviks. Plekhanov's colleague, Julius Martov, said the Bolshevik Centre was something between a secret factional central committee and a criminal gang.[6] The Tiflis Committee of the party expelled Stalin and several members for the robbery.[65][66] The party's investigations into Lenin's conduct were thwarted by the Bolsheviks.[6]

The robbery made the Bolsheviks even less popular in Georgia and left the Bolsheviks in Tiflis without effective leadership. After the death by natural causes of his wife Ekaterina Svanidze in November 1907, Stalin rarely returned to Tiflis. Other leading Bolsheviks in Georgia, such as Mikhail Tskhakaya and Filipp Makharadze, were largely absent from Georgia after 1907. Another prominent Tiflis Bolshevik, Stepan Shahumyan, moved to Baku. The Bolsheviks' popularity in Tiflis continued to fall, and by 1911, there were only about 100 Bolsheviks left in the city.[67]

The robbery also made the Bolshevik Centre unpopular more widely among European social democrat groups.[6] Lenin's desire to distance himself from the legacy of the robbery may have been one of the sources of the rift between him and Bogdanov and Krasin.[6] Stalin distanced himself from Kamo's gang and never publicized his role in the robbery.[65][68]

Later careers[edit]

After the Bolshevik Revolution of October 1917, many of those who had been involved in the robbery became high ranking Soviet officials. Lenin went on to become the first Soviet Premier, the post he held until his death in 1924, followed by Stalin as leader of the Soviet Union until his own death in 1953. Maxim Litvinov became a Soviet diplomat, serving as People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs (1930–1939). Leonid Krasin initially quit politics after the split from Lenin in 1909, but rejoined the Bolsheviks after the 1917 Revolution and served as the Soviet trade representative in London and as People's Commissar for Foreign Trade until his death in 1926.[6]

After Kamo's release from prison, he worked in the Soviet customs office, by some accounts because he was too unstable to work for the secret police.[41] He died in 1922 when a truck hit him while he was cycling.[41] Although there is no proof of foul play, some have theorized that Stalin ordered his death to keep him quiet.[69][70]

Monument[edit]

Erivansky Square, where the robbery took place, was renamed Lenin Square by the Soviet authorities in 1921, and a large statue of Lenin was erected in his honour in 1956.[71][72] Despite being convicted of the bloody robbery, Kamo was originally buried and had a monument erected in his honour in Pushkin Gardens, near Erivansky Square.[65][73] Created by the sculptor Iakob Nikoladze, it was removed during Stalin's rule, and Kamo's remains were moved to another location.[70] The statue of Lenin was torn down in August 1991—one of the final moments of the Soviet Union—and replaced by the Liberty Monument in 2006. The name of the square was changed from Lenin Square to Freedom Square in 1991.[71][74]

See also[edit]

- 1906 Helsinki bank robbery

- Bezdany raid, a train robbery in 1908

Notes[edit]

- a Sources give the date of the robbery as either 13 June 1907[10][30] or 26 June 1907,[28][75] depending on whether Old Style Julian calendar or New Style Gregorian calendar dates are used. The Russian government used the Julian calendar until February 1918 when it switched to the Gregorian calendar by skipping thirteen days in that year so that 31 January 1918 was followed by 14 February 1918.[76] For purposes of this article, dates are provided according to Gregorian calendar dates.

- b Joseph Stalin used a variety of names during his lifetime. His original Georgian name was "Josef Vissarionovich Djugashvili", but his friends and family called him "Soso".[77][78] During his early revolutionary years, which would include the years of the 1907 Tiflis bank robbery, he mostly went by the revolutionary nom de guerre "Koba", which he obtained from a character in Alexander Kazbegi's novel The Patricide.[77][79] He published poetry under the name "Soselo".[77] In 1912, he began to use the name Stalin and later adopted this as his surname after October 1917.[77] The name Stalin is translated to mean "Man of Steel".[77][80] This article uses the name by which he is most commonly known to the world, "Joseph Stalin", for clarity.

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e Kun 2003, p. 75.

- ^ (White, James D. Red Hamlet: The Life and Ideas of Alexander Bogdanov, 2018, p. 179).

- ^ a b Trotsky 1970, Chapter IV: The period of reaction.

- ^ Geifman 1993, pp. 4, 21–22.

- ^ a b c Sebag Montefiore 2008, pp. 3–4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Nicolaevsky 1995.

- ^ a b c Souvarine 2005, p. 94.

- ^ Souvarine 2005, pp. 91–92, 94.

- ^ Ulam 1998, pp. 262–263.

- ^ a b c d e Brackman 2000, p. 58.

- ^ Sebag Montefiore 2008, pp. 4–5.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Sebag Montefiore 2008, pp. 6–7.

- ^ a b c Sebag Montefiore 2008, p. 4.

- ^ a b Sebag Montefiore 2008, p. 165.

- ^ Roberts 2022, pp. 37.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Sebag Montefiore 2008, p. 11.

- ^ a b c Kun 2003, pp. 77–78.

- ^ a b c d e f Sebag Montefiore 2008, p. 8.

- ^ Sebag Montefiore 2008, p. 178.

- ^ a b c d e Brackman 2000, p. 60.

- ^ a b Shub 1960, p. 231.

- ^ Sebag Montefiore 2008, p. 5.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Brackman 2000, p. 59.

- ^ Brackman 2000, pp. 58–59.

- ^ Sebag Montefiore 2008, p. 127.

- ^ Salisbury, Harrison E. (1981). Black Night White Snow. Da Capo Press. p. 221. ISBN 978-0-306-80154-9.

- ^ Kun 2003, p. 76.

- ^ a b c d e "Bomb Kills Many; $170,000 Captured". The New York Times. 1907-06-27. Retrieved 2010-11-30.

- ^ a b c Sebag Montefiore 2008, p. 9.

- ^ a b Shub 1960, p. 227.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Sebag Montefiore 2008, p. 13.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Sebag Montefiore 2008, p. 12.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Sebag Montefiore 2008, p. 14.

- ^ Kun 2003, pp. 73–75.

- ^ Yuri Felshtinsky, ed. (1999). Был ли Сталин агентом охранки? (Was Stalin an Okhrana agent?) (in Russian). Teppa. ISBN 978-5-300-02417-8. Retrieved 2010-12-19.

- ^ Sebag Montefiore 2008, pp. 14, 87.

- ^ Brackman 2000, p. 61.

- ^ a b c d e f Brackman 2000, p. 62.

- ^ a b c Krupskaya 1970, Chapter:Again Abroad – End of 1907

- ^ Sebag Montefiore 2008, p. 181.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Ulam 1998, pp. 279–280.

- ^ a b Brackman 2000, p. 64.

- ^ a b "Held As Tiflis Robbers". The New York Times. 1908-01-19. Retrieved 2018-08-10.

- ^ a b c Brackman 2000, pp. 63–64.

- ^ "Alleged Nihilists Arrested In Paris; Russian Students, Man and Woman, Suspected of Many Political Crimes. Lived in Latin Quarter, Their Rooms Rendezvous for Revolutionists – Believed That They Planned Assassinations" (PDF). The New York Times. 1908-02-08. Retrieved 2010-12-02.

- ^ Krupskaya 1970, Chapter:Years of Reaction – Geneva – 1908

- ^ a b c d e Krupskaya 1970, Chapter:Paris – 1909–1910

- ^ a b Souvarine 2005, p. 103.

- ^ Souvarine 2005, p. 101.

- ^ Brackman 2000, p. 55.

- ^ a b Souvarine 2005, pp. 101–102.

- ^ Shub 1960, p. 234.

- ^ Shub 1960, pp. 236–237.

- ^ Shub 1960, p. 237.

- ^ a b Souvarine 2005, p. 102.

- ^ a b c Shub 1960, p. 238.

- ^ Brackman 2000, pp. 57–58.

- ^ Shub 1960, p. 239.

- ^ Brackman 2000, p. 67.

- ^ Shub 1960, pp. 246–247.

- ^ a b Shub 1960, p. 244.

- ^ Shub 1960, pp. 244–245.

- ^ Shub 1960, p. 245.

- ^ Shub 1960, p. 246.

- ^ a b c d Sebag Montefiore 2008, p. 15.

- ^ Souvarine 2005, p. 99.

- ^ Jones 2005, pp. 220–221.

- ^ Kun 2003, p. 77.

- ^ Brackman 2000, p. 33.

- ^ a b Sebag Montefiore 2008, p. 370.

- ^ a b Burford 2008, p. 113.

- ^ "Communist Purge of Security Chiefs Continues". The Sydney Morning Herald. Fairfax Media. AAP. 1953-07-17. p. 1. Retrieved 2010-12-02.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Soviet Union. Posolʹstvo (U.S) (1946). "USSR Information Bulletin". USSR Information Bulletin. 6 (52–67): 15. Retrieved 2010-12-03.

- ^ Remnick, David (1990-07-05). "The Day Lenin Fell On His Face; In Moscow, the Icons Of Communism Are Toppling". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2012-07-25. Retrieved 2010-12-02.

- ^ Sebag Montefiore 2008, p. 3.

- ^ Christian 1997, p. 6.

- ^ a b c d e Sebag Montefiore 2008, p. xxxi.

- ^ Sebag Montefiore 2008, p. 23.

- ^ Sebag Montefiore 2008, p. 63.

- ^ Sebag Montefiore 2008, p. 268.

Bibliography[edit]

- Brackman, Roman (2000). "Chapter 7: The Great Tiflis Bank Robbery". The Secret File of Joseph Stalin: A Hidden Life. Portland, Oregon: Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-7146-5050-0.

- Burford, Tim (2008). Georgia. Bradt Travel Guides. Chalfont St Peter, Buckinghamshire: Bradt Travel Guides. ISBN 978-1-84162-261-3.

- Christian, David (1997). "Introduction". Imperial and Soviet Russia: Power, Privilege, and the Challenge of Modernity. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-312-17352-4.

- Geifman, Anna (1993). Thou Shalt Kill: Revolutionary Terrorism in Russia, 1894–1917. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-08778-8.

- Jones, Stephen F. (2005). Socialism in Georgian Colors: The European Road to Social Democracy, 1883–1917. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01902-7.

- Krupskaya, Nadezhda (1970). Reminiscences of Lenin. Marxists Internet Archive. Retrieved 2010-12-10.

- Kun, Miklós (2003). "Chapter 5: Why Stalin Was Called a 'Mail-Coach Robber'". Stalin: An Unknown Portrait. New York: Central European University Press. ISBN 978-963-9241-19-0.

- Nicolaevsky, Boris (1995). "On the History of the Bolshevist Center". In Yu. G. Felshtinsky (ed.). Secret Pages of History (in Russian). Moscow: Humanities Publishing. ISBN 978-5-87121-007-9.

- Roberts, Geoffrey (2022). Stalin's Library: A Dictator and his Books. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300265590.

- Sebag Montefiore, Simon (2008). "Prologue: The Bank Robbery". Young Stalin. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-1-4000-9613-8.

- Shub, David (1960). "Kamo—the Legendary Old Bolshevik of the Caucasus". The Russian Review. 19 (3): 227–247. doi:10.2307/126539. JSTOR 126539. (subscription required)

- Souvarine, Boris (2005). "Chapter IV – A Professional Revolutionary". Stalin: A Critical Survey of Bolshevism. New York: Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4191-1307-9.

- Trotsky, Leon (1970). "Chapter IV: The Period of Reaction". Stalin: An Appraisal of the Man and His Influence. New York: Stein and Day. LCCN 67028713. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- Ulam, Adam (1998). "The Years of Waiting: 1908–1917". The Bolsheviks: The Intellectual and Political History of the Triumph of Communism in Russia. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-07830-7.

External links[edit]

Media related to 1907 Tiflis bank robbery at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to 1907 Tiflis bank robbery at Wikimedia Commons