Battles of Bergisel

| Battles of Bergisel | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Tyrolean Rebellion | |||||||

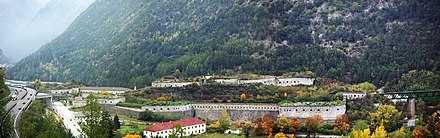

Statue of Andreas Hofer near Bergisel in Innsbruck | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 5,000 | 5,000 (later 15,000) | ||||||

The Battles of Bergisel were four battles fought between Tyrolese civilian militiamen and a contingent of Austrian government troops and the military forces of Emperor Napoleon I of France and King of Kingdom of Bavaria against at the Bergisel hill near Innsbruck. The battles, which occurred on 25 May, 29 May, 13 August, and 1 November 1809, were part of the Tyrolean Rebellion and the War of the Fifth Coalition.

The Tyrolean civilian forces, loyal to Austria,[citation needed] were led by militia commander Andreas Hofer, Josef Speckbacher, Peter Mayr, Capuchin Father Joachim Haspinger, and Major Martin Teimer. The Bavarians were led by French Marshal François Joseph Lefebvre, and Bavarian Generals Bernhard Erasmus von Deroy and Karl Philipp von Wrede. After being driven from Innsbruck at the start of the revolt, the Bavarians twice reoccupied the city and were chased out again. After the final battle in November, the rebellion was suppressed.

Background[edit]

After his humiliating defeat of the Austrian Empire in the War of the Third Coalition, Napoleon transferred the County of Tyrol to Bavaria. When the new rulers imposed conscription and Bavarian legal codes on the territory, they flouted ancient Tyrolean social, military and religious rights.[1] Furthermore the Bavarian king ordered a compulsory vaccination program concerning smallpox, which the Tyroleans saw as blasphemy. Before the outbreak of the War of the Fifth Coalition, Austrian agents circulated in the Tyrol to take advantage of the existing tensions. When Archduke Charles, Duke of Teschen invaded Bavaria on 10 April 1809, the Tyrol militia decided to revolt.[2]

Battles[edit]

The Tyrol 1809 Order of Battle lists the regular units and organizations of both armies.

First Battle of Bergisel (12 April 1809)[edit]

On 11 April Hofer and 5,000 armed peasants scored a victory at Sterzing in the South Tyrol when they captured 420 Bavarians of the 4th Light Infantry Battalion.[3]

Under Teimer and other leaders, the Tyroleans won a brilliant initial success. Attacked incessantly for 48 hours, Lieutenant General Baron Kinkel surrendered his Innsbruck garrison of 3,860 Bavarian soldiers on 13 April.[4] A body of 2,050 French conscripts under hard-drinking General of Division Baptiste Pierre Bisson unwittingly marched into the trap. After an ineffectual defense, the French also put up the white flag.[5] The rebels seized five cannon, two mortars, considerable equipment, and many muskets. The captured material would keep the Tyrolean supplied with weapons for months.

May 1809[edit]

Soon reinforced by a regular Austrian division under Feldmarschallleutnant Johann Gabriel Chasteler de Courcelles, the Tyrolese posed a threat to the rear areas of Napoleon's armies in northern Italy and Bavaria. One column of irregulars stiffened by a few regulars under General-Major Franz Fenner raided the area of Lake Garda in Italy. In consequence, Viceroy of Italy Eugène de Beauharnais was forced to provide substantial Franco-Italian garrisons to guard the area.[4]

In early May, Napoleon directed Marshal François Joseph Lefebvre and the VII Corps (made up of Bavarians) to move against the Tyrol.[6] The Bavarian garrison of Kufstein Fortress was relieved on 11 May. Lefebvre routed Chasteler at the Battle of Wörgl on 13 May.[7] After several more actions, Lefebvre occupied Innsbruck around 19 May.[8]

Second Battle of Bergisel (29 May 1809)[edit]

On 25 May 1809, Lieutenant General Deroy's 3rd Bavarian Division clashed with the Tyrolese rebels at the Bergisel. Deroy committed 4,000 troops and 12 artillery pieces to the combat. Hofer commanded the rebel army and his lieutenants were Speckbacher, Teimer, Josef Eisenstecken, and Oberstleutnant Ertel. Hofer's army included 9,400 armed rebels and 900 Austrian regulars. The regulars included one battalion each of the 16th Lusignan Infantry Regiment and 25th De Vaux Infantry Regiment, two companies of the 9th Jäger battalion, a half-squadron of the 3rd O'Reilly Chevau-léger Regiment and five guns. The Bavarians lost 20 to 70 dead and 100 to 150 wounded, while inflicting losses of 50 dead and 30 wounded on the Tyrolese. Though historian Digby Smith labels the action a Bavarian victory, his narrative says the battle was a draw. He notes that the rebels, discouraged that more local people had not joined the revolt, retreated to the south.[9]

The Tyrolese returned on 29 May and subjected Deroy to a second attack, which he resisted with 5,240 troops organized in 12 battalions, eight squadrons, and 18 guns. The 13,600 Tyrolese irregulars were joined by 1,200 Austrian regulars and six pieces of artillery. The rebels included 35 North Tyrol and 61 South Tyrol schützen and landsturm companies. The Bavarians managed to hold their ground after suffering 87 dead, 156 wounded, and 53 missing. The rebels lost 90 dead and 160 wounded.[10] The next day, low on ammunition and food, Deroy evacuated Innsbruck and retreated to Kufstein Fortress in the north, see also de:Bernhard Erasmus von Deroy

July and early August 1809[edit]

After Napoleon's war-winning victory at the Battle of Wagram on 5 and 6 July,[11] Lefebvre invaded the Tyrol again and Deroy won a minor action at the Lueg Pass on 24 July. However, the Tyrol responded to Hofer's call for another uprising.[12] About 5,000 Tyrolese led by Haspinger and Speckbacher smashed French General Marie François Rouyer's 3,600 Confederation of the Rhine troops at Franzensfeste on 4 and 5 August. The Ducal Saxon Infantry Regiment was annihilated with 988 casualties, while the Bavarians lost an additional 100 men and two cannons. Tyrolean losses were trifling. The valley is still known as the Sachsenklemme (Saxon Trap). The next day, Lefebvre arrived with the 1st Bavarian Division, but he was also repulsed by the Tyrolese.[13] On 8 and 9 August at Prutz, 920 Tyrolese led by Roman Burger routed Oberst Burscheidt's 2,000 soldiers of the 10th Bavarian Infantry and 2nd Dragoon Regiments, which belonged to Deroy's 3rd Division. The Tyrolese inflicted 200 killed and wounded on their enemies while capturing 1,200 men and two cannons. Rebel losses were only seven killed.[14]

Third Battle of Bergisel (13 August 1809)[edit]

On 13 August, Hofer and 18,000 Tyrolese fought Deroy's division in the third battle of Bergisel. Four Bavarian battalions belonging to General Siebein's 2nd Brigade lost 200 dead and 250 wounded. The 70 companies of rebels lost 100 dead and 220 wounded. After taking hostages from leading local families, Lefebvre abandoned Innsbruck and the last occupation troops were gone from the Tyrol by 18 August.[15]

September and October 1809[edit]

Speckbacher and 2,000 Tyrolean militiamen attacked the Bavarian garrisons in the villages of Lofer, Luftenstein, Unken, and Mellek on 25 September. Of the 700 soldiers belonging to the Leib Infantry Regiment # 1, 50 were killed and wounded, 300 captured, and 100 missing. The troops were dispersed with only two companies in each village. The detachment in Mellek broke out and retreated north to Bad Reichenhall; the other garrisons were wiped out.[16] On the same day Haspinger with 2,400 Tyrolese and four guns evicted General-Major Stengel's brigade from the Lueg Pass near Golling an der Salzach. The 3,500 Bavarians and three cannons retreated north to Salzburg. Lefebvre, with 2,000 of Stengel's troops attacked Hallein on 3 October. Haspinger's force, which had lingered in the town, was chased back into the mountains, leaving their six cannons behind.[17]

At this time, Jean-Baptiste Drouet, Comte d'Erlon replaced Lefebvre in command of VII Corps and the third invasion of Tyrol was launched. On 17 October, the 1st Bavarian Division led by General-Major Rechberg caught Speckbacher and his 2,000 men by surprise at Bodenbichl. The Tyrolese failed to properly picket their camp and the 3,000 Bavarians inflicted a serious defeat on the irregulars. Rebel losses were 300 dead and 400 captured, while the Bavarians admitted only seven casualties. For this action, Rechberg was awarded the Military Order of Max Joseph from his grateful sovereign.[17]

Fourth Battle of Bergisel (1 November 1809)[edit]

The fourth battle of Bergisel took place on 1 November 1809. Lieutenant General Wrede's 2nd Bavarian Division defeated Hofer's and Haspinger's 70 companies of Tyrolean militia. The Bavarians committed 6,000 troops and 12 guns to the action and lost only one killed and 40 wounded. The 8,535 Tyrolese suffered 350 killed, wounded, and captured, and abandoned five cannons. The fourth battle and the disaster at Bodenbichl broke the back of the rebellion.[18]

Hofer was betrayed to the French on 28 January 1810 and was executed on Napoleon's order on 20 February 1810 at Mantua in Italy.[15]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Arnold 1995, p. 20.

- ^ Arnold 1990, p. 67.

- ^ Smith 1998, p. 285.

- ^ a b Arnold 1995, p. 103.

- ^ Arnold 1995, p. 21.

- ^ Petre 1976, pp. 249–250.

- ^ Petre 1976, p. 263.

- ^ Petre 1976, p. 272.

- ^ Smith 1998, pp. 311–312.

- ^ Smith 1998, p. 313.

- ^ Smith 1998, p. 322.

- ^ Smith 1998, p. 326.

- ^ Smith 1998, p. 329.

- ^ Smith 1998, p. 330.

- ^ a b Smith 1998, p. 331.

- ^ Smith 1998, pp. 332–333.

- ^ a b Smith 1998, p. 333.

- ^ Smith 1998, p. 336.

References[edit]

- Arnold, James R. (1990). Crisis on the Danube: Napoleon's Austrian Campaign of 1809. New York, N.Y.: Paragon House. ISBN 1-55778-137-0.

- Arnold, James R. (1995). Napoleon Conquers Austria. Westport, Conn.: Praeger Publishers. ISBN 0-275-94694-0.

- Petre, F. Loraine (1976). Napoleon and the Archduke Charles. New York, N.Y.: Hippocrene Books.

- Smith, Digby (1998). The Napoleonic Wars Data Book. London: Greenhill. ISBN 1-85367-276-9.

External links[edit]

- Battle of Bergisel cyclorama

Media related to Battles of Bergisel at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Battles of Bergisel at Wikimedia Commons

| Preceded by Battle of Medellín |

Napoleonic Wars Battles of Bergisel |

Succeeded by Battle of Sacile |