Caelum

| Constellation | |

| |

| Abbreviation | Cae |

|---|---|

| Genitive | Caeli[1] |

| Pronunciation | /ˈsiːləm/, genitive /ˈsiːlaɪ/ |

| Symbolism | the chisel |

| Right ascension | 04h 19.5m to 05h 05.1m [2] |

| Declination | −27.02° to −48.74°[2] |

| Area | 125 sq. deg. (81st) |

| Main stars | 4 |

| Bayer/Flamsteed stars | 8 |

| Stars with planets | 1 |

| Stars brighter than 3.00m | 0 |

| Stars within 10.00 pc (32.62 ly) | 0 |

| Brightest star | α Cae (4.45m) |

| Messier objects | 0 |

| Meteor showers | 1 |

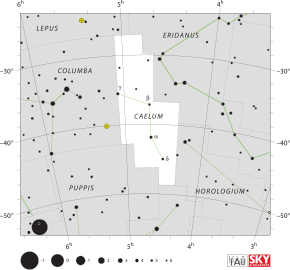

| Bordering constellations | Columba Lepus Eridanus Horologium Dorado Pictor |

| Visible at latitudes between +40° and −90°. Best visible at 21:00 (9 p.m.) during the month of January. | |

Caelum /ˈsiːləm/ is a faint constellation in the southern sky, introduced in the 1750s by Nicolas Louis de Lacaille and counted among the 88 modern constellations. Its name means "chisel" in Latin, and it was formerly known as Caelum Sculptorium ("Engraver's Chisel"); it is a rare word, unrelated to the far more common Latin caelum, meaning "sky", "heaven", or "atmosphere".[3] It is the eighth-smallest constellation, and subtends a solid angle of around 0.038 steradians, just less than that of Corona Australis.

Due to its small size and location away from the plane of the Milky Way, Caelum is a rather barren constellation, with few objects of interest. The constellation's brightest star, Alpha Caeli, is only of magnitude 4.45, and only one other star, (Gamma) γ1 Caeli, is brighter than magnitude 5 . Other notable objects in Caelum are RR Caeli, a binary star with one known planet approximately 20.13 parsecs (65.7 ly) away; X Caeli, a Delta Scuti variable that forms an optical double with γ1 Caeli; and HE0450-2958, a Seyfert galaxy that at first appeared as just a jet, with no host galaxy visible.

History[edit]

Caelum was incepted as one of fourteen southern constellations in the 18th century by Nicolas Louis de Lacaille, a French astronomer and celebrated of the Age of Enlightenment.[4] It retains its name Burin among French speakers, latinized in his catalogue of 1763 as Caelum Sculptoris (“Engraver's Chisel”).[5]

Francis Baily shortened this name to Caelum, as suggested by John Herschel.[6] In Lacaille's original chart, it was shown as a pair of engraver's tools: a standard burin and more specific shape-forming échoppe tied by a ribbon, but came to be ascribed a simple chisel.[6] Johann Elert Bode stated the name as plural with a singular possessor, Caela Scalptoris – in German (die ) Grabstichel (“the Engraver’s Chisels”) – but this did not stick.[7][8]

Characteristics[edit]

Caelum is bordered by Dorado and Pictor to the south, Horologium and Eridanus to the east, Lepus to the north, and Columba to the west. Covering only 125 square degrees, it ranks 81st of the 88 modern constellations in size.

Its main asterism consists of four stars, and twenty stars in total are brighter than magnitude 6.5 .[1]

The constellation's boundaries, as set by Belgian astronomer Eugène Delporte in 1930, are a 12-sided polygon. In the equatorial coordinate system, the right ascension coordinates of these borders lie between 04h 19.5m and 05h 05.1m and declinations of −27.02° to −48.74°.[2] The International Astronomical Union (IAU) adopted the three-letter abbreviation “Cae” for the constellation in 1922.[9]

Its main stars are visible in favourable conditions and with a clear southern horizon, for part of the year as far as about the 41st parallel north[1][a]

These stars avoid being engulfed by daylight for some of every day (when above the horizon) to viewers in mid- and well-inhabited higher latitudes of the Southern Hemisphere. Caelum shares with (to the north) Taurus, Eridanus and Orion midnight culmination in December (high summer), resulting in this fact. In winter (such as June) the constellation can be observed sufficiently inset from the horizons during its rising before dawn and/or setting after dusk as it culminates then at around mid-day, well above the sun. In South Africa, Argentina, their sub-tropical neighbouring areas and some of Australia in high June the key stars may be traced before dawn in the east; near the equator the stars lose night potential in May to June; they ill-compete with the Sun in northern tropics and sub-tropics from late February to mid-September with March being unfavorable as to post-sunset due to the light of the Milky Way.

Notable features[edit]

Stars[edit]

Caelum is a faint constellation: It has no star brighter than magnitude 4 and only two stars brighter than magnitude 5.

Lacaille gave six stars Bayer designations, labeling them Alpha (α ) to Zeta (ζ ) in 1756, but omitted Epsilon (ε ) and designated two adjacent stars as Gamma (γ ). Bode extended the designations to Rho (ρ ) for other stars, but most of these have fallen out of use.[7] Caelum is too far south for any of its stars to bear Flamsteed designations.[b]

The brightest star, (Alpha) α Caeli, is a double star, containing an F-type main-sequence star of magnitude 4.45 and a red dwarf of magnitude 12.5 , 20.17 parsecs (65.8 ly) from Earth.[11][12] (Beta) β Caeli, another F-type star of magnitude 5.05 , is further away, being located 28.67 parsecs (93.5 ly) from Earth. Unlike α, β Caeli is a subgiant star, slightly evolved from the main sequence.[13] (Delta) δ Caeli, also of magnitude 5.05 , is a B-type subgiant and is much farther from Earth, at 216 parsecs (700 ly).[14]

(Gamma) γ1Caeli is a double-star with a red giant primary of magnitude 4.58 and a secondary of magnitude 8.1 . The primary is 55.59 parsecs (181.3 ly) from Earth. The two components are difficult to resolve with small amateur telescopes because of their difference in visual magnitude and their close separation.[15] This star system forms an optical double with the unrelated X Caeli (previously named γ2Caeli), a Delta Scuti variable located 98.33 parsecs (320.7 ly) from Earth.[16] These are a class of short-period (six hours at most) pulsating stars that have been used as standard candles and as subjects to study astroseismology.[17] X Caeli itself is also a binary star, specifically a contact binary,[18] meaning that the stars are so close that they share envelopes. The only other variable star in Caelum visible to the naked eye is RV Caeli, a pulsating red giant of spectral type M1III,[19] which varies between magnitudes 6.44 and 6.56 .[20]

Three other stars in Caelum are still occasionally referred to by their Bayer designations, although they are only on the edge of naked-eye visibility. (Nu) ν Caeli[21] is another double star, containing a white giant of magnitude 6.07[22] and a star of magnitude 10.66, with unknown spectral type.[23] The system is approximately 52.55 parsecs (171.4 ly) away.[22] (Lambda) λ Caeli,[24] at magnitude 6.24, is much redder and farther away, being a red giant around 227 parsecs (740 ly) from Earth.[25] (Zeta) ζ Caeli is even fainter, being only of magnitude 6.36 . This star, located 132 parsecs (430 ly) away, is a K-type subgiant of spectral type K1.[26] The other twelve naked-eye stars in Caelum are not referred to by Bode's Bayer designations anymore, including RV Caeli.

One of the nearest stars in Caelum is the eclipsing binary star RR Caeli, at a distance of 20.13 parsecs (65.7 ly).[27] This star system consists of a dim red dwarf and a white dwarf.[28] Despite its closeness to the Earth, the system's apparent magnitude is only 14.40[27] due to the faintness of its components, and thus it cannot be easily seen with amateur equipment. In 2012, the system was found to contain a giant planet, and there is evidence for a second substellar body.[29] The system is a post-common-envelope binary and is losing angular momentum over time, which will eventually cause mass transfer from the red dwarf to the white dwarf. In approximately 9–20 billion years, this will cause the system to become a cataclysmic variable.[30]

Deep-sky objects[edit]

Due to its small size and location away from the plane of the Milky Way, Caelum is rather devoid of deep-sky objects, and contains no Messier objects. The only deep-sky object in Caelum to receive much attention is HE0450-2958, an unusual Seyfert galaxy. Originally, the jet's host galaxy proved elusive to find, and this jet appeared to be emanating from nothing.[31] Although it has been suggested that the object is an ejected supermassive black hole,[32] the host is now agreed to be a small galaxy that is difficult to see due to light from the jet and a nearby starburst galaxy.[33]

The 13th magnitude planetary nebula PN G243-37.1 is also in the eastern regions of the constellation. It is one of only a few planetary nebulae found in the galactic halo, being 20000±14000 light-years below the Milky Way's 1000 light-year-thick disk.[34]

Galaxies NGC 1595, NGC 1598, and the Carafe galaxy are known as the Carafe group. The Carafe galaxy is a Seyfert galaxy with ring. Its location is 4:28 / -47°54' (2000.0). [35][36]

Notes[edit]

- ^ While parts technically reach the horizon to observers between 41°N and 62°N, stars within a few degrees of the horizon are to all intents and purposes unobservable.[1]

- ^ Southern constellations such as Caelum have no Flamsteed designations because Flamsteed only catalogued stars that were visible from England,.[10]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d Ridpath, Ian. "Constellations: Andromeda–Indus". Star Tales. self-published. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- ^ a b c "Caelum, Constellation Boundary". The Constellations. International Astronomical Union. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- ^ Charlton T. Lewis, Ph.D. and. Charles Short, A Latin Dictionary Oxford University Press, 1879. Entries for caelum and caelum.

- ^ Ridpath, Ian. "Lacaille". Star Tales. self-published. Retrieved 3 May 2014.

- ^ Coelum australe stelliferum, N. L. de Lacaille, 1763

- ^ a b Ridpath, Ian. "Caelum". Star Tales. self-published. Retrieved 3 May 2014.

- ^ a b Wagman, Morton (2003). Lost Stars: Lost, Missing, and Troublesome Stars from the Catalogues of Johannes Bayer, Nicholas Louis de Lacaille, John Flamsteed, and Sundry Others. Blacksburg, VA: The McDonald & Woodward Publishing Company. pp. 58–59. ISBN 978-0-939923-78-6.

- ^ J. E. Bode: Allgemeine Beschreibung und Nachweisung der Gestirne nebst Verzeichniß der geraden Aufsteigung und Abweichung von 17240 Sternen, Doppelsternen, Nebelflecken und Sternhaufen. Berlin, 1801, p.17

- ^ Russell, H. N. (1922). "The New International Symbols for the Constellations". Popular Astronomy. 30: 469–71. Bibcode:1922PA.....30..469R.

- ^ Kaler, J. B. "Star Names". University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign. Retrieved 11 May 2014.

- ^ "* Alpha Caeli – Star in double system". SIMBAD. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- ^ "GJ 174.1 B – Flare star". SIMBAD. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- ^ "LTT 2063 – High proper-motion Star". SIMBAD. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- ^ "* Delta Caeli – Star". SIMBAD. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- ^ "* Gamma Caeli – Star". SIMBAD. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- ^ "V* X Caeli – Variable Star of Delta Scuti type". SIMBAD. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- ^ Templeton, M. (16 July 2010). "Delta Scuti and the Delta Scuti Variables". AAVSO Website. American Association of Variable Star Observers. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- ^ X., V. S.; Patrick, W. (4 January 2010). "X Caeli". AAVSO Website. American Association of Variable Star Observers. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- ^ "V* RV Caeli – Pulsating variable Star". SIMBAD. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- ^ X., V. S. (25 August 2009). "RV Caeli". AAVSO Website. American Association of Variable Star Observers. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

- ^ Ashland Astronomy Studio: Where Art and Science Converge. "Nu Caeli (HIP 22488)". Archived from the original on 29 January 2014. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- ^ a b "HR 1557 – Star in double system". SIMBAD. Retrieved 15 January 2013.

- ^ "CD-41 1593B – Star in double system". SIMBAD. Retrieved 15 January 2013.

- ^ Ashland Astronomy Studio: Where Art and Science Converge. "Lambda Caeli (HIP 21998)". Archived from the original on 29 January 2014. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- ^ "HR 1518 – Star". SIMBAD. Retrieved 15 January 2013.

- ^ "Zeta Caeli – Star". SIMBAD. Retrieved 15 January 2013.

- ^ a b "V* RR Caeli – Eclipsing binary of Algol type (detached)". SIMBAD. Retrieved 15 January 2013.

- ^ Bruch, A.; Diaz, M. P. (1998). "The Eclipsing Precataclysmic Binary RR Caeli". The Astronomical Journal. 116 (2): 908. Bibcode:1998AJ....116..908B. doi:10.1086/300471.

- ^ Qian, S. B.; Liu, L.; Zhu, L. Y.; Dai, Z. B.; Fernández Lajús, E.; Baume, G. L. (2012). "A circumbinary planet in orbit around the short-period white dwarf eclipsing binary RR Cae". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society: Letters. 422 (1): L24–L27. arXiv:1201.4205. Bibcode:2012MNRAS.422L..24Q. doi:10.1111/j.1745-3933.2012.01228.x. S2CID 119190656.

- ^ Maxted, P. F. L.; O'Donoghue, D.; Morales-Rueda, L.; Napiwotzki, R.; Smalley, B. (2007). "The mass and radius of the M-dwarf in the short-period eclipsing binary RR Caeli". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 376 (2): 919–928. arXiv:astro-ph/0702005. Bibcode:2007MNRAS.376..919M. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2007.11564.x. S2CID 3569936.

- ^ Magain, P.; Letawe, G. R.; Courbin, F. D. R.; Jablonka, P.; Jahnke, K.; Meylan, G.; Wisotzki, L. (2005). "Discovery of a bright quasar without a massive host galaxy". Nature. 437 (7057): 381–384. arXiv:astro-ph/0509433. Bibcode:2005Natur.437..381M. doi:10.1038/nature04013. PMID 16163349. S2CID 4303895.

- ^ Haehnelt, M. G.; Davies, M. B.; Rees, M. J. (2006). "Possible evidence for the ejection of a supermassive black hole from an ongoing merger of galaxies". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society: Letters. 366 (1): L22–L25. arXiv:astro-ph/0511245. Bibcode:2006MNRAS.366L..22H. doi:10.1111/j.1745-3933.2005.00124.x. S2CID 18433710.

- ^ Feain, I. J.; Papadopoulos, P. P.; Ekers, R. D.; Middelberg, E. (2007). "Dressing a Naked Quasar: Star Formation and Active Galactic Nucleus Feedback in HE 0450−2958". The Astrophysical Journal. 662 (2): 872. arXiv:astro-ph/0703101. Bibcode:2007ApJ...662..872F. doi:10.1086/518027. S2CID 15556375.

- ^ Brown, A. G. A.; et al. (Gaia collaboration) (August 2018). "Gaia Data Release 2: Summary of the contents and survey properties". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 616. A1. arXiv:1804.09365. Bibcode:2018A&A...616A...1G. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201833051.

- ^ Sky Catalogue 2000.0, Volume 2: Double Stars, Variable Stars and Nonstellar Objects (edited by Alan Hirshfeld and Roger W. Sinnott, 1985). Chapter 3: Glossary of Selected Astronomical Names.

- ^ Hugh C. Maddocks, Deep-Sky Name Index 2000.0 (Foxon-Maddocks Associates, 1991).

External links[edit]