China Girl (song)

| "China Girl" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Single by Iggy Pop | ||||

| from the album The Idiot | ||||

| B-side | "Baby" | |||

| Released | May 1977 | |||

| Recorded | July–August 1976 | |||

| Studio | ||||

| Genre | ||||

| Length |

| |||

| Label | RCA | |||

| Songwriter(s) |

| |||

| Producer(s) | David Bowie | |||

| Iggy Pop singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

"China Girl" is a song written by Iggy Pop and David Bowie in 1976, and first released by Pop on his debut solo album, The Idiot (1977). Inspired by an affair Pop had with a Vietnamese woman, the lyrics tell a story of unrequited love for the protagonist's Asian girlfriend, realizing by the end that his Western influences are corrupting her. Like the rest of The Idiot, Bowie wrote the music and Pop improvised the lyrics while standing at the microphone. The song was released as a single in May 1977 and failed to chart.

Bowie re-recorded a more well-known version during the sessions for his 1983 album Let's Dance, reportedly to assist Pop with his poor finances at the time. It was co-produced by Nile Rodgers, who transformed the song into a pop number with an Asian-inspired guitar riff. Bowie's version was released as the second single from the album in May 1983, reaching number two in the UK and number 10 in the US. Its accompanying music video featured New Zealand actress Geeling Ng. Containing an interracial romance and clashing cultural perspectives, Bowie said the video was intended as a statement against racism. He performed the song frequently during his concert tours. Bowie's version has also appeared on compilation albums and lists of the artist's best songs.

Iggy Pop original version[edit]

Recording[edit]

Written by David Bowie and Iggy Pop, "China Girl" began as a piece called "Borderline" that the two came up with one night residing at the Château d'Hérouville in Hérouville, France, during the sessions for Pop's debut solo album The Idiot. During a visit by the French actor and singer Jacques Higelin, Pop had a brief affair with Higelin's Vietnamese girlfriend Kuelan Nguyen. The two did not speak the same language, communicating through gestures and expressions. Their brief encounter inspired the lyrics for "China Girl", which Pop improvised while standing at the microphone.[a][2][3]

The song was recorded between June and July at the Château, with overdubs recorded in August at Musicland Studios in Munich, Germany.[2] As with the rest of The Idiot, Bowie composed the music,[1] contributing piano, synthesizer, alto saxophone, rhythm guitar, toy piano, and backing vocals. The remaining lineup featured Phil Palmer on lead guitar, Laurent Thibault on bass, and Michel Santangeli on drums.[2] The song was mixed in Berlin at Hansa Studio 1.[4]

Music and lyrics[edit]

It's about a very blundering, blustering rock 'n' roll hero who has big plans and Western habits [and] who becomes enchanted and subdued by a Chinese girl.[2]

—Iggy Pop on "China Girl"

"China Girl" is the most upbeat track on The Idiot.[5][6] Built on E minor chord progressions, the song is led primarily by distorted guitar and synthesizer.[2][7] It features a raw and unpolished production compared to Bowie's version.[8] Lyrically, the song is a tale of unrequited love for the protagonist's Asian girlfriend, realizing by the end that his Western influences are corrupting her.[7] The protagonist's "Shhh ..." was a direct quote from Nguyen after Pop confessed his feelings for her one night.[9] He speaks of natural elements—falling stars and hearts beating "as loud as thunder"—before introducing modernization—Marlon Brando, "visions of swastikas", television, and cosmetics—that will "ruin everything you are".[2] Author James E. Perone argues that the use of swastikas could reference both the symbol of Hinduism and the fascism of Nazi Germany, "intriguing images and questions" for listeners.[10] According to author Chris O'Leary, the song's title represents a double entendre, indicating "China" as "pure heroin" and "the girl's fragility".[2] Bowie said the song was about "invasion and exploitation".[7]

Release[edit]

The Idiot was released through RCA Records on 18 March 1977;[11] "China Girl" was sequenced as the final track on side one of the original LP.[2] Deemed an album highlight by multiple reviewers,[12][13] ZigZag magazine's Kris Needs felt the song was the only choice for a single from the album.[6] In May, "China Girl" was released as a single, backed by the album track "Baby", and failed to chart.[3][14]

Pop played "China Girl" throughout the 1977 Idiot Tour, with Bowie on keyboards.[15] According to O'Leary, these performances differed from the studio recording in that they were catchier and featured "frenetic drumming" and less "krautrock drone".[2] Live recordings from the tour have been released on the Pop compilations 1977 (2007) and The Bowie Years (2020), the latter also featuring an alternate mix of the song.[16][17]

Praised for Bowie's musical arrangement,[7][4] Siouxsie Sioux of Siouxsie and the Banshees later said she prefers Pop's version of "China Girl".[18] According to Iggy Pop biographer Joe Ambrose, The Idiot songs "China Girl", "Nightclubbing", and "Sister Midnight" "became part of the soundtrack of the age, the synthesized post-punk Eighties".[18] The song was later included on Pop's compilation A Million in Prizes: The Anthology (2005).[19]

Personnel[edit]

According to Chris O'Leary and Thomas Jerome Seabrook:[2][7]

- Iggy Pop – vocals

- David Bowie – treated piano, synthesizers, alto saxophone, toy piano, rhythm guitar, backing vocal

- Phil Palmer – lead guitar

- Laurent Thibault – bass guitar

- Michel Santangeli – drums

Technical

- David Bowie – producer

- Laurent Thibault – engineer

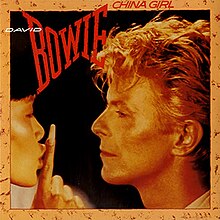

David Bowie version[edit]

| "China Girl" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Single by David Bowie | ||||

| from the album Let's Dance | ||||

| B-side | "Shake It" | |||

| Released | 31 May 1983 | |||

| Recorded | December 1982 | |||

| Studio | Power Station (New York City) | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length |

| |||

| Label | EMI America | |||

| Songwriter(s) |

| |||

| Producer(s) |

| |||

| David Bowie singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Music video | ||||

| "China Girl" on YouTube | ||||

Recording and composition[edit]

Bowie recorded his own version of "China Girl" during the sessions for his 1983 album Let's Dance, reportedly to assist Pop with his poor finances at the time.[2][7][15] Bowie played Pop's original for producer Nile Rodgers, believing it could be a hit.[20] Transforming it into a pop and new wave number,[21][22] the producer used Rufus's "Sweet Thing" as a basis for the opening riff to add a Chinese feel.[20] The song ends with a reprise of this "faux-Asian" introduction.[10] According to biographer Nicholas Pegg, the song's placement on Let's Dance provides a basis for the album's primary themes of "cultural identity and desperate love".[3] Both Pop and Bowie versions feature the same melody and use of Chinese bells.[23]

Co-produced by Bowie and Rodgers,[2] the song was recorded at the Power Station in New York City during the first three weeks of December 1982. The sessions were engineered by Bob Clearmountain.[24] The lineup featured Rodgers on rhythm guitar, Carmine Rojas on bass, Robert Sabino on keyboards and synthesizers, Omar Hakim on drums, Sammy Figueroa on percussion, and the trio of Frank Simms, George Simms, and David Spinner on backing vocals.[2] Then-unknown Texas blues guitarist Stevie Ray Vaughan played lead guitar, hired by Bowie after seeing Vaughan perform at the 1982 Montreux Jazz Festival in Switzerland.[25][26] According to biographer Chris O'Leary, Vaughan initially played longer than his allotted measures during his first solo, resulting in him ending on an unintended note. He wanted to correct it before Bowie insisted the mistake be kept.[2] Bowie himself played no instruments.[27]

Release[edit]

"China Girl" was first released in its full-length form on Let's Dance on 14 April 1983,[28] sequenced as the second track on side one of the original LP, between "Modern Love" and the title track.[29] The song was subsequently released in edited form as the second single from the album on 31 May 1983,[30][31] with album track "Shake It" as the B-side.[32] Bowie had intended "China Girl" to be the album's lead single before Rodgers convinced him to release "Let's Dance" first.[2] Entering the UK Singles Chart on 11 June, the single peaked at number two,[31] held off the top spot by the Police's "Every Breath You Take". In the US, it reached number ten on the Billboard Hot 100.[3]

The single edit of "China Girl" has appeared on the Bowie compilations Changesbowie (1990),[33] The Singles Collection (1993),[34] Best of Bowie (2002),[35] The Best of David Bowie 1980/1987 (2007),[36] Nothing Has Changed (2014) and Legacy (The Very Best of David Bowie) (2016).[37][38] Both single and album cuts were remastered and released on the box set Loving the Alien (1983–1988) in 2018.[39]

Music video[edit]

The song's music video was directed by David Mallet and was shot in February 1983 in the Chinatown district of Sydney, Australia, simultaneously with the video for "Let's Dance", and features New Zealand model and actress Geeling Ng.[3][20][40] Fascinated by Australia's large Chinese community, Bowie said that the video for "China Girl" was "a vignette of my continuing fascination with all things Asian."[3] As the video for "Let's Dance" had offered commentary on racism in Australia, "China Girl"'s video was described by Bowie at the time as a "very simple, very direct" statement against racism.[40][41] The video ends with Bowie and Ng recreating a scene from the 1953 film From Here to Eternity, lying naked in the surf.[3][42] Ng remembered Bowie as "unfailingly polite, charming, and a gentleman."[43]

The video depicts clashing cultural perspectives with an interracial romance and, according to Ruth Tam of The Washington Post, parodies Asian female stereotypes as a way to condemn racism and denounce the West's disparaging view of the East; Ng is transformed into a Westerner's vision of a Chinese goddess and shots of barbed wire offer totalitarian undertones.[3][41] In a negative assessment published in 1993, Columbia University professor Ellie M. Hisama condemned the video's portrayal of the "China Girl" as lacking in "identity or self-determination", rather simply "reduced to a sex and a race".[44] In his book Future Nostalgia: Performing David Bowie, author Sheldon Waldrep doubted that many people understood the video's message, saying: "Maybe some of [the joke] comes through in the music video if you interpret it as ironically as Bowie meant it to be interpreted."[45] The author also attributed the video's subtleness for people's failure to understand its message: "He put layers of meaning in there hoping that people would get it."[45]

The video was banned from New Zealand and some other countries at the time.[31][46] Top of the Pops aired an edited video that censored the nudity by utilizing wide-shots and slow-motion edits.[3] The uncensored video was issued on the 1984 Video EP,[47] while the censored version later appeared on Best of Bowie in 2002.[3] The original video won an MTV video award for Best Male Video in 1984.[48]

Reception[edit]

Bowie's version of "China Girl" has received positive reviews, with many praising Rodgers's production and Bowie's vocal performance.[10][49][50][51] Reviewing the single on release, Cash Box said that it provided "a nice balance to the controlled frenzy" of "Let's Dance" with its "softer vocals and minimal instrumentation" and also said that the song is "neatly [framed]" by "an oriental-style riff."[52] In a retrospective review, BBC writer David Quantick commended Rodgers for taking a song with "paranoid references to 'visions of swastikas'" and transform it into a hit single.[49] AllMusic's Ned Raggett referred to it as "a prime example of early eighties mainstream music done right", praising the production, arrangement, and Vaughan's guitar solo as "add[ing] just enough bite without sending the tune off track".[50]

Due to its appearance on Let's Dance and success as a single, Bowie's version is more widely known than Pop's original; O'Leary argues that "China Girl" is a Bowie song "for much of the world".[2] Numerous reviewers have compared the two versions. O'Leary states that whereas Pop's vocal was "sang in frenzy", Bowie's was "assured" and "playful".[2] Reviewing Let's Dance on release, NME's Charles Shaar Murray summarized: "Iggy's version was full of rage and pain, concentrating on the torment which only his lover could ease. Bowie's, on the other hand, focuses on the relief from pain, and the joy that can be brought by someone capable of bringing that relief."[53] Another reviewer from the same publication, Emily Barker, later said in 2018 that Bowie altered the original's "claustrophobic scratchiness" to "extroverted disco".[54] Far Out writers Jack Whatley and Tom Taylor said that Bowie's version had "all the same sex appeal" as Pop's original, "with the benefit of a shower".[55] Mojo's Danny Eccelston found Bowie's version superior to the original.[56]

Following Bowie's death in January 2016, the writers of Rolling Stone named "China Girl" one of the 30 most essential songs of his catalogue.[57] The song has placed in other lists ranking Bowie's best songs by The Telegraph (included),[58] Smooth Radio (12),[59] Far Out (29),[55] NME (27),[54] Consequence of Sound (60),[51] and Mojo (63).[56] In a 2016 list ranking every Bowie single from worst to best, Ultimate Classic Rock placed it at number 29 (out of 119).[60]

Live performances[edit]

Bowie regularly performed "China Girl" on the 1983 Serious Moonlight and 1987 Glass Spider tours;[3] recordings appeared on the accompanying Serious Moonlight and Glass Spider concert videos in 1983 and 1988, respectively.[61] The former performance was later released on the live album Serious Moonlight (Live '83), included in Loving the Alien (1983–1988) in 2018 and released separately the following year.[62] "China Girl" was also performed on the 1990 Sound+Vision tour.[3]

A semi-acoustic version appeared during Bowie's Bridge School benefit concert on 20 October 1996. The following year, he played an impromptu jam of the track on The Rosie O'Donnell Show for Rosie O'Donnell, retitled "Rosie Girl". The song made return appearances on the 1999 Hours, 2000 summer shows, 2002 Heathen and 2003–2004 A Reality tours, often featuring a cabaret-style opening by Mike Garson that led into a bass-heavy rendition more akin to Pop's original.[3] Other live recordings have been released on VH1 Storytellers in 2009,[63] Glastonbury 2000 in 2018,[64] and A Reality Tour in 2010.[65]

Personnel[edit]

According to Chris O'Leary:[2]

- David Bowie – lead vocal

- Stevie Ray Vaughan – lead guitar

- Nile Rodgers – rhythm guitar

- Carmine Rojas – bass

- Robert Sabino – keyboards, synthesizer

- Omar Hakim – drums

- Sammy Figueroa – percussion

- Frank Simms, George Simms, David Spinner – backing vocals

Technical

- David Bowie – producer

- Nile Rodgers – producer

- Bob Clearmountain – engineer

Charts[edit]

Weekly charts[edit]

|

Year-end charts[edit]

|

Certifications[edit]

| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| Canada (Music Canada)[96] | Gold | 50,000^ |

| United Kingdom (BPI)[97] | Silver | 250,000^ |

|

^ Shipments figures based on certification alone. | ||

Later versions[edit]

- James Cook – Ashes to Ashes: A Tribute to David Bowie (1998)[98]

Notes[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b Seabrook 2008, pp. 75–88.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r O'Leary 2019, chap. 1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Pegg 2016, pp. 60–62.

- ^ a b Trynka 2007, pp. 242–250.

- ^ Demorest, Stephen (April 1977). "From Russia with Love: Bowie's Iggy". Phonograph Record. Archived from the original on 24 September 2020. Retrieved 28 February 2021 – via Rock's Backpages (subscription required).

- ^ a b Needs, Kris (April 1977). "Iggy Pop: The Idiot". ZigZag. Archived from the original on 13 January 2022. Retrieved 28 February 2021 – via Rock's Backpages (subscription required).

- ^ a b c d e f Seabrook 2008, pp. 91–92.

- ^ Pegg 2016, pp. 487–488.

- ^ Trynka 2007, pp. 208–209.

- ^ a b c Perone 2007, pp. 87–88.

- ^ Deming, Mark. "The Idiot – Iggy Pop". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 30 December 2014. Retrieved 8 December 2014.

- ^ "Top Album Picks" (PDF). Billboard. 26 March 1977. p. 78. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 November 2022. Retrieved 27 November 2022 – via worldradiohistory.com.

- ^ Demorest, Stephen (April 1977). "From Russia with Love: Bowie's Iggy". Phonograph Record. Archived from the original on 24 September 2020. Retrieved 28 February 2021 – via Rock's Backpages (subscription required).

- ^ Ambrose 2004, p. 309.

- ^ a b Ambrose 2004, pp. 219–220.

- ^ Pegg 2016, p. 497.

- ^ Kreps, Daniel (10 April 2020). "Iggy Pop Preps 7-CD 'The Bowie Years' Box Set". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 7 May 2023. Retrieved 7 May 2023.

- ^ a b Ambrose 2004, p. 178.

- ^ Deming, Mark. "A Million in Prizes: The Anthology – Iggy Pop". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 7 May 2023. Retrieved 7 May 2023.

- ^ a b c Trynka 2011, p. 382.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Let's Dance – David Bowie". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 17 January 2016. Retrieved 13 January 2016.

- ^ Perone 2018, p. 129.

- ^ Spitz 2009, pp. 273, 322–323.

- ^ Buckley 2005, pp. 334–345, 359.

- ^ Pegg 2016, pp. 400–404.

- ^ Buckley 2005, pp. 340–341.

- ^ White, Timothy (May 1983). "David Bowie Interview". Musician. No. 55. pp. 52–66, 122.

- ^ O'Leary 2019, chap. 5.

- ^ O'Leary 2019, Partial Discography.

- ^ Pegg 2016, pp. 60–61.

- ^ a b c "'China Girl' enters UK chart 35 years ago today". David Bowie Official Website. 11 June 2018. Archived from the original on 27 May 2022. Retrieved 29 May 2023.

- ^ Pegg 2016, p. 782.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Changesbowie – David Bowie". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 28 July 2019. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "The Singles: 1969–1993 – David Bowie". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 1 May 2021. Retrieved 7 May 2021.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Best of Bowie – David Bowie". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 1 April 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "The Best of David Bowie 1980–1987 – David Bowie". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 7 May 2023. Retrieved 7 May 2023.

- ^ Nothing Has Changed (CD liner notes). David Bowie. Europe: Parlophone. 2014. 825646205769.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ Monroe, Jazz (28 September 2016). "David Bowie Singles Collection Bowie Legacy Announced". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on 26 September 2019. Retrieved 29 September 2016.

- ^ Loving the Alien (1983–1988) (Box set booklet). David Bowie. UK, Europe & US: Parlophone. 2018. 0190295693534.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ a b Loder, Kurt (12 May 1983). "David Bowie: Straight Time". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 12 June 2016. Retrieved 13 June 2016.

- ^ a b Tam, Ruth (20 January 2016). "How David Bowie's 'China Girl' used racism to fight racism". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 20 January 2016. Retrieved 3 June 2016.

- ^ Trynka 2011, pp. 384–385.

- ^ Simpson, Dave (23 February 2013). "David Bowie and me". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2 October 2013. Retrieved 7 May 2023.

- ^ Hisama, Ellie M. (May 1993). "Postcolonialism on the Make: The Music of John Mellencamp, David Bowie and John Zorn". Popular Music. 12 (2). Cambridge University Press: 91–104. doi:10.1017/S0261143000005493. JSTOR 931292. S2CID 162801278.

- ^ a b Waldrep, Shelton (25 August 2015). Future Nostalgia: Performing David Bowie. New York City: Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1623566920.

- ^ "David Bowie's 'China Girl' Co-Star Says Music Video Changed Her Life". Billboard. 13 January 2016. Archived from the original on 3 August 2016. Retrieved 3 June 2016.

- ^ Pegg 2016, p. 640.

- ^ "MTV Video Music Awards 1984". MTV. Archived from the original on 28 August 2008. Retrieved 3 June 2016.

- ^ a b Quantick, David. "David Bowie Let's Dance Review". BBC. Archived from the original on 9 January 2016. Retrieved 17 March 2016.

- ^ a b Raggett, Ned. "'China Girl' – David Bowie". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 7 May 2023. Retrieved 7 May 2023.

- ^ a b Cosores, Philip (8 January 2017). "David Bowie's Top 70 Songs". Consequence of Sound. Archived from the original on 20 September 2021. Retrieved 19 September 2021.

- ^ "Reviews" (PDF). Cash Box. 28 May 1983. p. 8. Retrieved 19 July 2022 – via worldradiohistory.com.

- ^ Murray, Charles Shaar (16 April 1983). "David Bowie: Let's Dance". NME. Archived from the original on 12 April 2021. Retrieved 12 March 2021 – via Rock's Backpages (subscription required).

- ^ a b Barker, Emily (8 January 2018). "David Bowie's 40 greatest songs – as decided by NME and friends". NME. Archived from the original on 3 November 2019. Retrieved 16 February 2020.

- ^ a b Whatley, Jack; Taylor, Tom (8 January 2022). "David Bowie's 50 greatest songs of all time". Far Out. Archived from the original on 26 February 2022. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

- ^ a b Eccleston, Danny (February 2015). "David Bowie – The 100 Greatest Songs". Mojo. No. 255. p. 63.

- ^ "David Bowie: 30 Essential Songs". Rolling Stone. 11 January 2016. Archived from the original on 2 January 2023. Retrieved 7 May 2023.

- ^ "David Bowie's 20 greatest songs". The Telegraph. 10 January 2021. Archived from the original on 3 February 2021. Retrieved 15 April 2021.

- ^ Eames, Tom (26 June 2020). "David Bowie's 20 greatest ever songs, ranked". Smooth Radio. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 15 April 2021.

- ^ "Every David Bowie Single Ranked". Ultimate Classic Rock. 14 January 2016. Archived from the original on 24 July 2021. Retrieved 19 September 2021.

- ^ Pegg 2016, pp. 640, 643.

- ^ "Loving the Alien breaks out due February". David Bowie Official Website. 7 January 2019. Archived from the original on 15 January 2019. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- ^ Sisson, Patrick (15 July 2009). "David Bowie: VH1 Storytellers Album Review". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on 20 September 2021. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- ^ Collins, Sean T. (5 December 2018). "David Bowie: Glastonbury 2000 Album Review". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on 11 July 2019. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "A Reality Tour – Davis Bowie". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 18 August 2017. Retrieved 11 August 2017.

- ^ Kent, David (1993). Australian Chart Book 1970–1992. St Ives, NSW: Australian Chart Book. ISBN 978-0-646-11917-5.

- ^ "David Bowie – China Girl" (in German). Ö3 Austria Top 40. Retrieved 4 June 2016.

- ^ "David Bowie – China Girl" (in Dutch). Ultratop 50. Retrieved 4 June 2016.

- ^ "Top RPM Singles: Issue 6232." RPM. Library and Archives Canada. Retrieved 4 June 2016.

- ^ Pennanen, Timo (2006). Sisältää hitin – levyt ja esittäjät Suomen musiikkilistoilla vuodesta 1972 (in Finnish). Helsinki: Kustannusosakeyhtiö Otava.

- ^ "Le Détail par Artiste". InfoDisc (in French). Select "David Bowie" from the artist drop-down menu. Archived from the original on 12 August 2016. Retrieved 4 June 2016.

- ^ "David Bowie – China Girl" (in German). GfK Entertainment charts. Retrieved 4 June 2016.

- ^ "The Irish Charts – Search Results – China Girl". Irish Singles Chart. Retrieved 4 June 2016.

- ^ "Nederlandse Top 40 – week 27, 1983" (in Dutch). Dutch Top 40. Retrieved 4 June 2016.

- ^ "David Bowie – China Girl" (in Dutch). Single Top 100. Retrieved 4 June 2016.

- ^ "David Bowie – China Girl". Top 40 Singles. Retrieved 4 June 2016.

- ^ "Topp 20 Single uke 25, 1983 – VG-lista. Offisielle hitlister fra og med 1958" (in Norwegian). VG-lista. Retrieved 4 June 2016.

- ^ "South African Rock Lists Website SA Charts 1969 – 1989 Acts (B)". The South African Rock Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 2 August 2017. Retrieved 4 June 2016.

- ^ "David Bowie – China Girl". Singles Top 100. Retrieved 4 June 2016.

- ^ a b "David Bowie – China Girl". Swiss Singles Chart. Retrieved 4 June 2016.

- ^ "Official Singles Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 4 June 2016.

- ^ "David Bowie Chart History (Hot 100)". Billboard. Retrieved 4 June 2016.

- ^ "David Bowie Chart History (Dance Club Songs)". Billboard. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- ^ "David Bowie Chart History (Mainstream Rock)". Billboard. Retrieved 4 June 2016.

- ^ "David Bowie – China Girl" (in French). Les classement single. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Official Singles Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 4 June 2016.

- ^ "David Bowie Chart History (Hot Rock & Alternative Songs)". Billboard. Retrieved 4 June 2016.

- ^ "Rock Digital Songs – The week of January 30, 2016". Billboard. 13 December 2013. Retrieved 4 June 2016.

- ^ "Ultratop Jaaroverzichten 1983". Ultratop 50 (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 26 January 2014. Retrieved 4 June 2016.

- ^ "Top RPM Singles: Issue 6699." RPM. Library and Archives Canada. Retrieved 4 June 2016.

- ^ "Top 100 Single-Jahrescharts 1983". GfK Entertainment Charts (in German). Archived from the original on 9 May 2015. Retrieved 4 June 2016.

- ^ "Top 100-Jaaroverzicht van 1983". Dutch Top 40 (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 4 June 2016.

- ^ "Dutch Jaaroverzichten Single 1984". Single Top 100 (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 14 April 2016. Retrieved 4 June 2016.

- ^ "Official New Zealand Music Chart - End of Year Charts 1983". Official New Zealand Music Chart. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- ^ "Top 100 Hits for 1983". Billboard Hot 100. Archived from the original on 8 January 2014. Retrieved 4 June 2016.

- ^ "Canadian single certifications – David Bowie – China Girl". Music Canada.

- ^ "British single certifications – David Bowie – China Girl". British Phonographic Industry.

- ^ Bill Cummings (18 March 2013). "Ashes To Ashes: A Compilation of David Bowie Covers by Various Artists | God Is In The TV". Godisinthetvzine.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2 July 2014. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

Sources[edit]

- Ambrose, Joe (2004). Gimme Danger: The Story of Iggy Pop. London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-1-84449-328-9.

- Buckley, David (2005) [1999]. Strange Fascination – David Bowie: The Definitive Story. London: Virgin Books. ISBN 978-0-7535-1002-5.

- O'Leary, Chris (2019). Ashes to Ashes: The Songs of David Bowie 1976–2016. London: Repeater Books. ISBN 978-1-912248-30-8.

- Pegg, Nicholas (2016). The Complete David Bowie (Revised and Updated ed.). London: Titan Books. ISBN 978-1-78565-365-0.

- Perone, James E. (2007). The Words and Music of David Bowie. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-27599-245-3.

- Perone, James E (7 September 2018). Listen to New Wave Rock! Exploring a Musical Genre. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-Clio. ISBN 978-1-44085-969-4.

- Seabrook, Thomas Jerome (2008). Bowie in Berlin: A New Career in a New Town. London: Jawbone Press. ISBN 978-1-906002-08-4.

- Spitz, Marc (2009). Bowie: A Biography. New York City: Crown Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-307-71699-6.

- Trynka, Paul (2011). David Bowie – Starman: The Definitive Biography. New York City: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0-316-03225-4.

- Trynka, Paul (2007). Iggy Pop: Open Up and Bleed. New York City: Broadway Books. ISBN 978-0-7679-2319-4.

- 1977 singles

- 1983 singles

- British new wave songs

- David Bowie songs

- Iggy Pop songs

- EMI America Records singles

- MTV Video Music Award for Best Male Video

- Music videos directed by David Mallet (director)

- RCA Records singles

- Songs written by David Bowie

- Songs written by Iggy Pop

- Song recordings produced by David Bowie

- Song recordings produced by Nile Rodgers

- Songs against racism and xenophobia

- Songs about East Asian people