Declaration of Arbroath

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2018) |

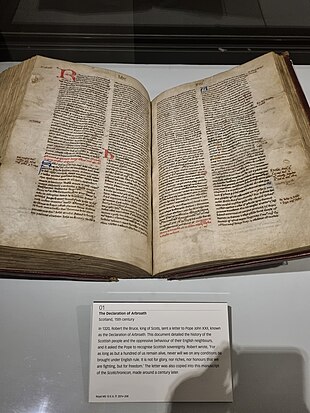

The Declaration of Arbroath (Latin: Declaratio Arbroathis; Scots: Declaration o Aiberbrothock; Scottish Gaelic: Tiomnadh Bhruis) is the name usually given to a letter, dated 6 April 1320 at Arbroath, written by Scottish barons and addressed to Pope John XXII.[1] It constituted King Robert I's response to his excommunication for disobeying the pope's demand in 1317 for a truce in the First War of Scottish Independence.[2] The letter asserted the antiquity of the independence of the Kingdom of Scotland, denouncing English attempts to subjugate it.[1][2]

Generally believed to have been written in Arbroath Abbey by Bernard of Kilwinning (or of Linton), then Chancellor of Scotland and Abbot of Arbroath,[3] and sealed by fifty-one magnates and nobles, the letter is the sole survivor of three created at the time. The others were a letter from the King of Scots, Robert I, and a letter from four Scottish bishops which all made similar points. The Declaration was intended to assert Scotland's status as an independent, sovereign state and defend Scotland's right to use military action when unjustly attacked.

Submitted in Latin, the Declaration was little known until the late 17th century, and is unmentioned by any of Scotland's major 16th-century historians.[1][4] In the 1680s, the Latin text was printed for the first time and translated into English in the wake of the Glorious Revolution, after which time it was sometimes described as a declaration of independence.[1]

Overview[edit]

The Declaration was part of a broader diplomatic campaign, which sought to assert Scotland's position as an independent kingdom,[5] rather than its being a feudal land controlled by England's Norman kings, as well as to lift the excommunication of Robert the Bruce.[6] The pope had recognised Edward I of England's claim to overlordship of Scotland in 1305 and Bruce was excommunicated by the Pope for murdering John Comyn before the altar at Greyfriars Church in Dumfries in 1306.[6] This excommunication was lifted in 1308; subsequently the pope threatened Robert with excommunication again if Avignon's demands in 1317 for peace with England were ignored.[2] Warfare continued, and in 1320 John XXII again excommunicated Robert I.[7] In reply, the Declaration was composed and signed and, in response, the papacy rescinded King Robert Bruce's excommunication and thereafter addressed him using his royal title.[2]

The wars of Scottish independence began as a result of the deaths of King Alexander III of Scotland in 1286 and his heir the "Maid of Norway" in 1290, which left the throne of Scotland vacant and the subsequent succession crisis of 1290–1296 ignited a struggle among the Competitors for the Crown of Scotland, chiefly between the House of Comyn, the House of Balliol, and the House of Bruce who all claimed the crown. After July 1296's deposition of King John Balliol by Edward of England and then February 1306's killing of John Comyn III, Robert Bruce's rivals to the throne of Scotland were gone, and Robert was crowned king at Scone that year.[8] Edward I, the "Hammer of Scots", died in 1307; his son and successor Edward II did not renew his father's campaigns in Scotland.[8] In 1309 a parliament held at St Andrews acknowledged Robert's right to rule, received emissaries from the Kingdom of France recognising the Bruce's title, and proclaimed the independence of the kingdom from England.[8]

By 1314 only Edinburgh, Berwick-upon-Tweed, Roxburgh, and Stirling remained in English hands. In June 1314 the Battle of Bannockburn had secured Robert Bruce's position as King of Scots; Stirling, the Central Belt, and much of Lothian came under Robert's control while the defeated Edward II's power on escaping to England via Berwick weakened under the sway of his cousin Henry, Earl of Lancaster.[7] King Robert was thus able to consolidate his power, and sent his brother Edward Bruce to claim the Kingdom of Ireland in 1315 with an army landed in Ulster the previous year with the help of Gaelic lords from the Isles.[7] Edward Bruce died in 1318 without achieving success, but the Scots campaigns in Ireland and in northern England were intended to press for the recognition of Robert's crown by King Edward.[7] At the same time, it undermined the House of Plantagenet's claims to overlordship of the British Isles and halted the Plantagenets' effort to absorb Scotland as had been done in Ireland and Wales. Thus were the Scots nobles confident in their letters to Pope John of the distinct and independent nature of Scotland's kingdom; the Declaration of Arbroath was one such. According to historian David Crouch, "The two nations were mutually hostile kingdoms and peoples, and the ancient idea of Britain as an informal empire of peoples under the English king's presidency was entirely dead."[8]

The text describes the ancient history of Scotland, in particular the Scoti, the Gaelic forebears of the Scots who the Declaration claims have origins in Scythia Major prior to migrating via Spain to Great Britain "1,200 years from the Israelite people's crossing of the Red Sea".[a] The Declaration describes how the Scots had "thrown out the Britons and completely destroyed the Picts",[b] resisted the invasions of "the Norse, the Danes and the English",[c] and "held itself ever since, free from all slavery".[d] It then claims that in the Kingdom of Scotland, "one hundred and thirteen kings have reigned of their own Blood Royal, without interruption by foreigners".[e] The text compares Robert Bruce with the Biblical warriors Judah Maccabee and Joshua.[f]

The Declaration made a number of points: that Edward I of England had unjustly attacked Scotland and perpetrated atrocities; that Robert the Bruce had delivered the Scottish nation from this peril; and, most controversially, that the independence of Scotland was the prerogative of the Scottish people, rather than the King of Scots.

Debates[edit]

Some have interpreted this last point as an early expression of popular sovereignty[9] – that government is contractual and that kings can be chosen by the community rather than by God alone. It has been considered to be the first statement of the contractual theory of monarchy underlying modern constitutionalism.[10]

It has also been argued that the Declaration was not a statement of popular sovereignty (and that its signatories would have had no such concept)[11] but a statement of royal propaganda supporting Bruce's faction.[12][13] A justification had to be given for the rejection of King John Balliol in whose name William Wallace and Andrew de Moray had rebelled in 1297. The reason given in the Declaration is that Bruce was able to defend Scotland from English aggression whereas King John could not.[14]

To this man, in as much as he saved our people, and for upholding our freedom, we are bound by right as much as by his merits, and choose to follow him in all that he does.

Whatever the true motive, the idea of a contract between King and people was advanced to the Pope as a justification for Bruce's coronation whilst John de Balliol, who had abdicated the Scottish throne, still lived as a Papal prisoner.[5]

There is also recent scholarship that suggests that the Declaration was substantially derived from the 1317 Irish Remonstrance, also sent in protest of English actions. There are substantial similarities in content between the 1317 Irish Remonstrance and the Declaration of Arbroath, produced three years later. It is also clear that the drafters of the Declaration of Arbroath would have access to the 1317 Irish Remonstrance, it having been circulated to Scotland in addition to the Pope. It has been suggested therefore that the 1317 Remonstrance was a "prototype" for the Declaration of Arbroath, suggesting Irish-Scottish cooperation in attempts to protest against English interference.[15]

Text[edit]

For the full text in Latin and a translation in English, See Declaration of Arbroath on WikiSource.

Signatories[edit]

There are 39 names—eight earls and thirty-one barons—at the start of the document, all of whom may have had their seals appended, probably over the space of some time, possibly weeks, with nobles sending in their seals to be used. The folded foot of the document shows that at least eleven additional barons and freeholders (who were not noble) who were not listed on the head were associated with the letter. On the extant copy of the Declaration there are only 19 seals, and of those 19 people only 12 are named within the document. It is thought likely that at least 11 more seals than the original 39 might have been appended.[16] The Declaration was then taken to the papal court at Avignon by Sir Adam Gordon, Sir Odard de Maubuisson, and Bishop Kininmund who was not yet a bishop and probably included for his scholarship.[5]

The Pope heeded the arguments contained in the Declaration, influenced by the offer of support from the Scots for his long-desired crusade if they no longer had to fear English invasion. He exhorted Edward II in a letter to make peace with the Scots. However, it did not lead to his recognising Robert as King of Scots, and the following year was again persuaded by the English to take their side and issued six bulls to that effect.[17]

Eight years later, on 1 March 1328, the new English king, Edward III, signed a peace treaty between Scotland and England, the Treaty of Edinburgh–Northampton. In this treaty, which was in effect until 1333, Edward renounced all English claims to Scotland. In October 1328, the interdict on Scotland, and the excommunication of its king, were removed by the Pope.[18]

Manuscript[edit]

The original copy of the Declaration that was sent to Avignon is lost. The only existing manuscript copy of the Declaration survives among Scotland's state papers, measuring 540mm wide by 675mm long (including the seals), it is held by the National Archives of Scotland in Edinburgh, a part of the National Records of Scotland.[19]

The most widely known English language translation was made by Sir James Fergusson, formerly Keeper of the Records of Scotland, from text that he reconstructed using this extant copy and early copies of the original draft.

G. W. S. Barrow has shown that one passage in particular, often quoted from the Fergusson translation, was carefully written using different parts of The Conspiracy of Catiline by the Roman author, Sallust (86–35 BC) as the direct source:[20]

... for, as long as but a hundred of us remain alive, never will we on any conditions be brought under English rule. It is in truth not for glory, nor riches, nor honours that we are fighting, but for freedom – for that alone, which no honest man gives up but with life itself.

List of signatories[edit]

Listed below are the signatories of the Declaration of Arbroath in 1320.[21]

The letter itself is written in Latin. It uses the Latin versions of the signatories' titles, and in some cases, the spelling of names has changed over the years. This list generally uses the titles of the signatories' Wikipedia biographies.

- Duncan, Earl of Fife (changed sides in 1332)

- Thomas Randolph, Earl of Moray (nephew and supporter of King Robert although briefly fought for the English after being captured by them, Guardian of the Realm after Robert the Bruce's death)

- Patrick Dunbar, Earl of March (or Earl of Dunbar) (changed sides several times)

- Malise, Earl of Strathearn (King Robert loyalist)

- Malcolm, Earl of Lennox (King Robert loyalist)

- William, Earl of Ross (earlier betrayed King Robert's female relatives to the English)

- Magnús Jónsson, Earl of Orkney

- William de Moravia, Earl of Sutherland

- Walter, High Steward of Scotland (King Robert loyalist)

- William de Soules, Lord of Liddesdale and Butler of Scotland (later imprisoned for plotting against the King)

- Sir James Douglas, Lord of Douglas (one of King Robert's leading loyalists)

- Roger de Mowbray, Lord of Barnbougle and Dalmeny (later imprisoned for plotting against King Robert)

- David, Lord of Brechin (later executed for plotting against King Robert)

- David de Graham of Kincardine

- Ingram de Umfraville (fought on the English side at Bannockburn but then changed sides to support King Robert)

- John de Menteith, guardian of the earldom of Menteith (earlier betrayed William Wallace to the English)

- Alexander Fraser of Touchfraser and Cowie

- Gilbert de la Hay, Constable of Scotland (King Robert loyalist)

- Robert Keith, Marischal of Scotland (King Robert loyalist)

- Henry St Clair of Rosslyn

- John de Graham, Lord of Dalkeith, Abercorn & Eskdale

- David Lindsay of Crawford

- William Oliphant, Lord of Aberdalgie and Dupplin (briefly fought for the English)

- Patrick de Graham of Lovat

- John de Fenton, Lord of Baikie and Beaufort

- William de Abernethy of Saltoun

- David Wemyss of Wemyss

- William Mushet

- Fergus of Ardrossan

- Eustace Maxwell of Caerlaverock

- William Ramsay

- William de Monte Alto, Lord of Ferne

- Alan Murray

- Donald Campbell

- John Cameron

- Reginald le Chen, Lord of Inverugie and Duffus

- Alexander Seton

- Andrew de Leslie

- Alexander Straiton

In addition, the names of the following do not appear in the document's text, but their names are written on seal tags and their seals are present:[22]

- Alexander de Lamberton (became a supporter of Edward Balliol after the Battle of Dupplin Moor, 1332)

- Edward Keith (subsequently Marischal of Scotland; d. 1346)

- Arthur Campbell (Bruce loyalist)

- Thomas de Menzies (Bruce loyalist)

- John de Inchmartin (became a supporter of Edward Balliol after the Battle of Dupplin Moor, 1332; d. after 1334)

- John Duraunt

- Thomas de Morham

Legacy[edit]

In 1998 former majority leader Trent Lott succeeded in instituting an annual "National Tartan Day" on 6 April by resolution of the United States Senate.[23] US Senate Resolution 155 of 10 November 1997 states that "the Declaration of Arbroath, the Scottish Declaration of Independence, was signed on April 6, 1320 and the American Declaration of Independence was modeled [sic] on that inspirational document".[24] However this claim is generally unsupported by historians.[25]

In 2016 the Declaration of Arbroath was placed on the UK Memory of the World Register, part of UNESCO's Memory of the World Programme.[26]

2020 was the 700th anniversary of the Declaration of Arbroath's composition; an Arbroath 2020 festival was arranged but postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh planned to display the document to the public for the first time in fifteen years.[4]

See also[edit]

- Declaration of independence

- Claim of Right 1989

- Barons' Letter of 1301, refutation of Papal claim to Scottish suzerainty by English barons

Notes[edit]

- ^ Latin: Undeque veniens post mille et ducentos annos a transitu populi israelitici per mare rubrum

- ^ Latin: expulsis primo Britonibus et Pictis omnino deletis

- ^ Latin: licet per Norwagienses, Dacos et Anglicos sepius inpugnata fuerit

- ^ Latin: ipsaque ab omni seruitute liberas, semper tenuit

- ^ Latin: In quorum Regno Centum et Tredescim Reges de ipsorum Regali prosapia, nullo alienigena interueniente, Regnauerunt

- ^ Latin: quasi alter Machabeus aut Josue

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d Cannon, John; Crowcroft, Robert, eds. (23 July 2015), "Arbroath, declaration of", A Dictionary of British History (3rd ed.), Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acref/9780191758027.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-175802-7, retrieved 6 April 2020

- ^ a b c d Webster, Bruce (2015), "Robert I", in Crowcroft, Robert; Cannon, John (eds.), The Oxford Companion to British History, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acref/9780199677832.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-967783-2, retrieved 6 April 2020

- ^ Scott 1999, p. 196.

- ^ a b "The most famous letter in Scottish history?". BBC News. 6 April 2020. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- ^ a b c Barrow 1984.

- ^ a b Lynch 1992.

- ^ a b c d Crouch, David (2018). Scotland, 1306–1513. Cambridge History of Britain. Cambridge University Press. pp. 309–328. doi:10.1017/9780511844379. ISBN 9780511844379. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d Crouch, David (2018). "Redefining Britain, 1217–1327". Medieval Britain, c. 1000–1500. Cambridge History of Britain. Cambridge University Press. p. 299. doi:10.1017/9780511844379.013. ISBN 9780511844379. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ McLean 2005, p. 247.

- ^ Cowan, Edward (2013). "for freedom alone": The declaration of arbroath, 1320. Edinburgh: Birlinn Ltd. p. 50. ISBN 978-1-84158-632-8.

- ^ Kellas 1998, p. 35.

- ^ Fugelso, Karl (2007). Memory and medievalism. D. S. Brewer. p. 138. ISBN 978-1-84384-115-9.

- ^ McCracken-Flesher, Caroline (2006). Culture, nation, and the new Scottish parliament. Bucknell University Press. p. 246. ISBN 978-0-8387-5547-1.

- ^ Robert Allan Houston; William Knox; National Museums of Scotland (2001). The new Penguin history of Scotland: from the earliest times to the present day. Allen Lane. ISBN 9780140263671.[page needed]

- ^ Duffy, Seán (13 December 2022). "The Irish Remonstrance: Prototype for the Declaration of Arbroath". Scottish Historical Review. 101 (3): 395–428. doi:10.3366/shr.2022.0576. S2CID 254676295.

- ^ "The seals on the Declaration of Arbroath". National Archives of Scotland. Retrieved 2 September 2011.

- ^ Scott 1999, p. 197.

- ^ Scott 1999, p. 225.

- ^ "National Archives of Scotland website feature". Archived from the original on 9 April 2009. Retrieved 4 April 2009.

- ^ G. W. S. Barrow, "The idea of freedom", Innes Review 30 (1979) 16–34 (reprinted in G. W. S. Barrow, Scotland and its Neighbours in the Middle Ages (London, Hambledon, 1992), chapter 1)

- ^ Brown, Keith. "The Records of the Parliaments of Scotland to 1707". Records of the Parliaments of Scotland. National Archives of Scotland. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- ^ "Declaration of Arbroath - Seals". National Archives of Scotland. Archived from the original on 6 January 2017. Retrieved 17 July 2016.

- ^ Cowan, Edward J. (2014). For Freedom Alone. Birlinn General. ISBN 978-1-78027-256-6.[page needed]

- ^ "Congressional Record Senate Articles". www.congress.gov. Retrieved 15 January 2016.

- ^ Neville, Cynthia (April 2005). "'For Freedom Alone': Review". The Scottish Historical Review. 84. doi:10.3366/shr.2005.84.1.104.

- ^ "Historic document awarded Unesco status". BBC News. 5 July 2016. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

Sources[edit]

- Barrow, G. W. S. (1984). Robert the Bruce and the Scottish Identity. Saltire Society. ISBN 978-0-85411-027-8.

- Kellas, James G. (1998). The politics of nationalism and ethnicity. Palgrave. ISBN 978-0-312-21553-8.

- Lynch, Michael (1992). Scotland: A New History. Pimlico. ISBN 978-0-7126-9893-1.

- McLean, Iain (2005). State of the Union: Unionism and the Alternatives in the United Kingdom Since 1707. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-925820-8.

- Scott, Ronald McNair (1999). Robert the Bruce: King of Scots. Canongate Books. ISBN 978-0-86241-616-4.

External links[edit]

Media related to Declaration of Arbroath at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Declaration of Arbroath at Wikimedia Commons Works related to Translation:Declaration of Arbroath at Wikisource

Works related to Translation:Declaration of Arbroath at Wikisource- Declaration of Arbroath Archived 9 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine on National Archives of Scotland website (includes full Latin text and English translation)

- Transcription and Translation of the Declaration of Arbroath, 6 April 1320

- 1320 works

- 1320 in Scotland

- 1320s in law

- 14th-century documents

- Letters (message)

- Robert the Bruce

- Declarations of independence

- National liberation movements

- Political history of Scotland

- Wars of Scottish Independence

- Scottish independence

- Avignon Papacy

- Popular sovereignty

- 1328 establishments in Scotland

- Medieval documents of Scotland

- Elective monarchy

- Arbroath