Edwin Bryant (alcalde)

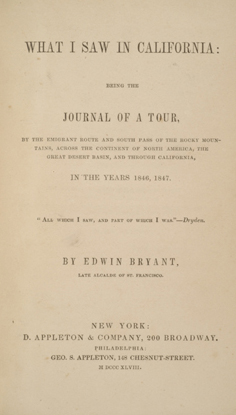

Edwin Bryant (August 21, 1805 – December 16, 1869) was a Kentucky newspaper editor whose popular 1848 book What I Saw in California describes his overland journey to California, his account of the infamous Donner Party, and his term as second alcalde, or pre-statehood mayor, of the city of San Francisco.

Early life and newspaper career[edit]

Bryant was born in Pelham, Massachusetts, the son of the first cousins Ichabod Bryant and Silence Bryant. Bryant had an unhappy childhood and his father was frequently imprisoned for debt. He lived with his uncle Bezabiel Bryant in Bedford, New York. He studied medicine under his uncle, Dr. Peter Bryant, father of the poet William Cullen Bryant.[1]: vi–vii [2]: 29 [3] He may have attended Brown University.[3] He founded the Providence, Rhode Island newspaper the Literary Cadet in 1826[2]: 29 [3][4] and edited the New York Examiner in Rochester, New York.[3]

In December 1830, Bryant joined George D. Prentice as co-editor of the Louisville Journal in Kentucky. Prentice, who had founded the newspaper only a month earlier, and Bryant penned blistering anti-Jacksonian editorials under the signatures "P" and "B". Following a trip to Frankfort, Kentucky to report on the Kentucky General Assembly, Bryant left the paper in May because it could not afford two editors. Bryant partnered with N.L. Finnell to edit the newly founded Lexington Observer, which a year later purchased and merged with the Kentucky Reporter (founded in 1807) to become the pro-Whig Party Lexington Observer and Reporter.[2]: 29–30

Bryant was hired to edit the Lexington Intelligencer in 1834 and spent the next decade at the newspaper, eventually becoming its owner before selling it to John C. Noble. Bryant penned frequent editorials, including editorials supporting the anti-Catholic nativism movement and a series of racist attacks on Vice President Richard Mentor Johnson for his black common law wife and two mixed race daughters. In 1844, at the urging of Whig politicians Henry Clay and John J. Crittenden, Bryant and Walter Newman Haldeman founded another pro-Whig newspaper, the Louisville Daily Dime, which was soon renamed the Louisville Courier.[2]: 30–31

Expedition to California[edit]

Citing poor health and the desire to write a book about the experience, in 1846 Bryant left the fledgling Courier and embarked on an expedition to California. Bryant and two others took a steamboat to Independence, Missouri, where they joined a large party gathered by General William Henry Russell (1802-1873), Kentucky lawyer and grandson of General William Russell, which included former Missouri Governor Lilburn Boggs and future Oregon legislator Jesse Quinn Thornton. The party began the journey to California in May. On the trail they were joined by a group of settlers who became the notorious Donner Party and attended the funeral of their first casualty, Sarah Keyes.[1]: viii–x [2]: 31–35 [5]: 23 Word of Bryant's limited medical experience had spread to other wagon trains and one enlisted him to help a ten-year-old boy with a crushed leg. Bryant helped a drover who had been a surgeon's assistant attempt an amputation with a handsaw, but the boy died during the primitive procedure.[6]

In June, concerned about the slow pace of the wagon train, Bryant and a small group of others rode ahead on pack mules, leaving most of the other pioneers, including the Donner Party, behind.[1]: x–xi Bryant's group took the Hastings Cutoff, a shorter but much rougher path that took them through the Great Salt Lake Desert. Bryant was concerned that the wagon train was unsuited for such a passage and wrote letters to James Reed and other members of the Donner Party to warn them away from the cutoff. Jim Bridger had been heavily promoting the Cutoff to bring emigrants to Fort Bridger, which the main route bypassed, and Bryant left his letters in the care of Bridger and Louis Vasquez, founders of the trading post. When the Donner Party arrived there, they did not receive Bryant's warning and proceeded down the Cutoff, a decision that led to their being stranded in the mountains that winter.[5]: 55–59 [7]

Bryant arrived in San Francisco in September 1846 and soon involved himself in the affairs of Alta California. He volunteered to serve with Captain John C. Frémont and served as 1st Lieutenant of Company H under Robert T. Jacobs. The next year, General Stephen W. Kearny appointed Bryant the second alcalde of San Francisco, a post in which he served from February to June 1847. The post is a predecessor to that of Mayor of San Francisco, but it also had judicial functions as well, and later in life Bryant was sometimes referred to as Judge Bryant. One of Bryant's key acts was to arrange for the sale of 450 lots of publicly owned waterfront property to private buyers, and arranged to purchase fourteen lots for himself for $4000. Originally intending to return home by sea, he accompanied General Kearny's overland party bringing Frémont east to stand trial for his actions in California. Later in 1847 he testified at Frémont's court martial.[2]: 36–39

In 1848, D. Appleton & Company published What I Saw in California: Being the Journal of a Tour, by the Emigrant Route and South Pass of the Rocky Mountains, across the Continent of North America, the Great Desert Basin, and through California, in the Years 1846, 1847, Bryant's account of his westward journey and his time in California. Coinciding with westward expansion and the California Gold Rush, Bryant's book became immensely popular and many emigrants and gold miners used Bryant's book as a guide. By 1850, there were seven editions printed in the United States, two in England, and one each in Sweden and France. In 1849, with much ceremony he led a company of 48 on a brisk return trip to California, where he sold the lots he had purchased for $100,000. He returned to Kentucky via Panama and New Orleans.[1]: xv–xviii [2]: 39–42

Later life[edit]

Wealthy thanks to real estate profits, book royalties, and lecture tours, Bryant settled in the literary colony of Pewee Valley, Kentucky. He built a large two-story house called Oaklea, which later appeared in the Little Colonel stories of Annie Fellows Johnston. There he lived out the American Civil War in safety.[1]: xviii–xix [2]: 42 [8]

Bryant made a final trip to California by railroad while in poor health in June 1869. In December, he was moved to the Willard Hotel in Louisville where he could be closer to medical assistance. There, he died after jumping out of a window.[1]: xix [2]: 42 Bryant's service was performed at Christ Church Cathedral and his body spent the next twelve years in the public receiving vault of Cave Hill Cemetery, until it was finally buried. In 1888, a nephew and brother-in-law had the body exhumed and reburied in the Bryant family section of Spring Grove Cemetery in Cincinnati.[1]: xx

Bryant Street in San Francisco is named for him.[9]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g Thomas D. Clark (1985). "Introduction". In Edwin Bryant (ed.). What I Saw in California. U of Nebraska Press. pp. v–xxi. ISBN 978-0-8032-6070-2. Retrieved 18 June 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Thomas D. Clark (October 1971). "Edwin Bryant and the Opening of the Road to California". In Roger Daniels (ed.). Essays in Western History: In Honor of Professor T. A. Larson. Vol. XXXVII. University of Wyoming. pp. 29–43.

- ^ a b c d Thomas D. Clark (1992). "Edwin Bryant". In John E. Kleber (ed.). The Kentucky Encyclopedia. University Press of Kentucky. p. 134. ISBN 978-0-8131-2883-2. Retrieved 18 June 2013.

- ^ "About Literary cadet, and Saturday evening bulletin. (Providence, R.I.) 1826-1827". Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Library of Congress. Retrieved 2013-06-18.

- ^ a b Ethan Rarick (4 January 2008). Desperate Passage:The Donner Party's Perilous Journey West. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-975670-4. Retrieved 18 June 2013.

- ^ Frank McLynn (1 January 2004). Wagons West: The Epic Story of America's Overland Trails. GROVE/ATLANTIC Incorporated. p. 289. ISBN 978-0-8021-4063-0. Retrieved 18 June 2013.

- ^ Tim McNeese (1 February 2009). The Donner Party: A Doomed Journey. Infobase Publishing. pp. 57–60. ISBN 978-1-60413-025-6. Retrieved 18 June 2013.

- ^ Anne Elizabeth Marshall (1 December 2010). Creating a Confederate Kentucky: The Lost Cause and Civil War Memory in a Border State. Univ of North Carolina Press. p. 140. ISBN 978-0-8078-9936-6. Retrieved 18 June 2013.

- ^ Street Names, San Francisco Museum Archived March 14, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

External links[edit]

- Works by Edwin Bryant at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Edwin Bryant at Internet Archive

- Edwin Bryant at Find a Grave

- Oaklea - Annie Fellows Johnston and the Little Colonel Stories

- Edwin Bryant summons, MSS SC 1161 at L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University