Hurricane Danny (1997)

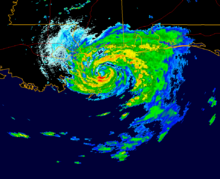

Danny at peak intensity making landfall in Louisiana on July 19 | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Formed | July 16, 1997 |

| Extratropical | July 26, 1997 |

| Dissipated | July 27, 1997 |

| Category 1 hurricane | |

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS/NWS) | |

| Highest winds | 80 mph (130 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 984 mbar (hPa); 29.06 inHg |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | 9 |

| Damage | $100 million (1997 USD) |

| Areas affected | Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Tennessee, Florida, Georgia, The Carolinas, Virginia, Massachusetts |

| IBTrACS | |

Part of the 1997 Atlantic hurricane season | |

Hurricane Danny was the only hurricane to make landfall in the United States during the 1997 Atlantic hurricane season, and the second hurricane and fourth tropical storm of the season. The system became the earliest-formed fifth tropical or subtropical storm of the Atlantic season in history when it attained tropical storm strength on July 17, and held that record until the 2005 Atlantic hurricane season when Tropical Storm Emily broke that record by several days. Like the previous four tropical or subtropical cyclones of the season, Danny had a non-tropical origin, after a trough spawned convection that entered the warm waters of the Gulf of Mexico. Danny was guided northeast through the Gulf of Mexico by two high pressure areas, a rare occurrence in the middle of July. After making landfall on the Gulf Coast, Danny tracked across the southeastern United States and ultimately affected parts of New England with rain and wind.

Danny is notable for its extreme rainfall, the tornadoes generated by it, and the destruction it produced on its path, causing a total of nine fatalities and $100 million (1997 USD, $190 million 2024 USD) in damage. The storm dropped a record amount of rainfall for Alabama, as at least 36.71 inches (932 mm) fell on Dauphin Island. Flooding, power outages, and erosion occurred in many areas of the Gulf Coast, and rescues had to be executed from flooded roadways. Tornadoes generated by Danny on the East Coast caused a great amount of damage. Of the nine fatalities caused by Danny, one happened off the coast of Alabama, four occurred in Georgia, two occurred in South Carolina, and two occurred in North Carolina.

Meteorological history[edit]

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

On July 13, a broad mid-tropospheric trough of low pressure over the southeastern United States helped to initiate an area of atmospheric convection over the lower Mississippi River Valley.[1] The area of convection moved southwards and appeared to contribute to the formation of a weak and isolated surface low pressure area in the Gulf of Mexico near the coast of Louisiana during the next day.[2] Over the next couple of days, the systems circulation gradually expanded, however, surface winds remained weak and convection over the system did not persist or become well organized.[1]

On July 16, deep convection increased and organized near the center, and oil rigs and surface buoys reported surface winds of 30 mph (45 km/h). Based on the observations, it is estimated the system developed into Tropical Depression Four on July 16 while located about 150 mi (240 km) south of the southwestern Louisiana coastline.

The depression slowly organized for the next day, as it drifted to the northeast. On July 17, the rate of organization and development of deep convection increased considerably, and the depression strengthened into Tropical Storm Danny later that day. From the night of July 17 through July 18, Danny quickly developed deep convection and banding features in the favorable environment of the Gulf of Mexico, and reached hurricane status later on July 18. Located between two high pressure systems, Danny continued its unusual July track to the northeast, and crossed over southeastern Louisiana near the Mississippi River Delta. A small storm, Danny continued to strengthen after reaching the coastal waters off Mississippi on the night of July 18, and attained a peak of 80 mph (130 km/h) early on July 19. The hurricane-force winds, however, were confined to the eyewall. After stalling near the mouth of Mobile Bay on July 19, Hurricane Danny turned to the east, and made its final landfall near Mullet Point, Alabama later that day.[2]

The storm rapidly weakened as it continued northward, and degenerated into a tropical depression by July 20. The weak depression moved through Alabama, Georgia, South Carolina, and North Carolina, maintaining a well-defined cloud signature.[2] Due to a front behind the system, Danny unusually strengthened to a tropical storm over North Carolina on July 24. This rare phenomenon occurred due to interaction with a developing trough and its associated baroclinic zone.[2][3] Danny entered the Atlantic Ocean, north of the North Carolina-Virginia border, near Virginia Beach. It quickly reached a secondary peak of 60 miles per hour (100 km/h), and continued rapidly northeastward towards the waters of the Atlantic. A strong mid to upper-level cyclone turned Danny northward, threatening Massachusetts. It stalled while just 30 miles (50 km) southeast of Nantucket on July 26, turned to the east out to sea, and became extratropical later that day. On July 27, the former hurricane merged with a frontal zone.[2]

Preparations[edit]

The National Hurricane Center issued a hurricane watch on July 17, as Danny strengthened to a tropical storm, for the coasts of Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama. When Danny strengthened to a hurricane on July 18, a few hours before its landfall in far southeastern Louisiana and over a day before landfall in Alabama, the hurricane watch was upgraded to a hurricane warning.[2] Grand Isle mayor Arthur Ballenger ordered the evacuation of the town's 1,500 residents, a decision made due to the large number of tourists on the island and to prevent anyone from being unable to leave the island. With a 5-foot (1.5 m) storm surge possibility, Danny had the potential to flood the only highway out of the island. Officials distributed sandbags to residents in St. Bernard Parish to seal off easily flooded roads, with officials recommending that residents leave the area.[4]

Prior to the arrival of the hurricane, the governors of Mississippi and Alabama declared disaster emergencies, expecting a 9-foot (2.7 m) storm surge and up to 20 inches (500 mm) of rain at that time. Six shelters were opened in Mobile County, Alabama, though few utilized them. Officials also considered opening shelters near local casinos and beaches in Biloxi, Mississippi.[5] Alabama Governor Fob James also activated the state's National Guard ahead of the storm and directed 30,000 sandbags to the Alabama coast for protection.[6]

Southeastern Massachusetts also had a tropical storm warning issued, a few hours before sustained tropical storm force winds affected the area and less than 12 hours before its closest approach to the coastline.[2]

Impact[edit]

As a small storm, Hurricane Danny only caused a damage toll of $100 million (1997 USD, $190 million 2024 USD). A total of 4 direct and 5 indirect deaths resulted from the effects of Danny.[2]

Gulf Coast[edit]

Heavy rain and winds buffeted many parishes located east of the city of New Orleans.[2][5] A small radius near the center of the storm had much of the extreme rainfall, and limited the flooding, which could have been disastrous if it were widespread.[2][7] Grand Isle and portions of the lower Plaquemines Parish were the worst hit in Louisiana. Additionally, Grand Isle reported a wind gust of 100 mph (160 km/h) and a storm surge of 5.2 feet (1.6 m).[7] At New Orleans International Airport, sustained winds of 28 mph (45 km/h) and gusts of 33 mph (53 km/h) were reported on July 19.[8] A gauge reported a water level of 4.85 feet (1.48 m) in Venice. Storm tides were 2 to 3 feet (0.61 to 0.91 meters) above normal on average.[7]

At least 10,000 people lost electricity in Louisiana. Furthermore, 130 boats were damaged or sunk at a large marina in Buras, Louisiana, due to the storm surge of over 4 feet (1.2 m), in a matter of minutes.[5] Both Grand Isle and Grand Terre Island received erosion on their shores, while many commercial fishing boats in Grand Isle were also heavily damaged.[9][10] Around 160 households and 80 businesses reported damage on Grand Isle. Jefferson Parish and Plaquemines Parish had $1.5 million (1997 USD$, 2.85 million 2024 USD) and $3.5 million (1997 USD$, 6.64 million 2024 USD) total in damage respectively.[7] Significant flooding happened throughout Jefferson Parish, with the floods affecting a total of 163 houses and 84 businesses. Meanwhile, in Plaquemines Parish, ten houses and 35 trailers had damage, with 8 businesses at least partially flooded and 40 commercial fishing boats also damaged. Lafourche Parish had no significant damage to report.[8] Empire and Venice were the most damaged areas in Plaquemines Parish. In the areas of Plaquemines Parish within the hurricane protection levees, trees, power lines, house roofs, and mobile homes sustained damage, in addition to localized flooding throughout the parish after about 10 inches of rain. In lower Terrebonne Parish, some highways were flooded, due to storm tides, and a few roads were also flooded in St. Bernard and Orleans parishes, which were outside the hurricane protection levees. Negligible damage occurred elsewhere in the extreme southeastern portion of Louisiana, due to Danny being a small tropical cyclone and a minimal hurricane.[7]

Eastern Jackson County had the greatest impact throughout Mississippi. Pascagoula reported a wind gust of 35 mph (56 km/h) on July 19. Pascagoula airport reported 7.87 inches (200 mm) of rain from July 17 through July 19. Some streets and a few homes were flooded in far southeastern Jackson County, in areas of poor drainage systems. The coast of Mississippi had no significant damage according to emergency management officials.[11] An oil rig off the coast of Pascagoula was ripped from its moorings and collided with a tank that spilled 500 gallons (1,892 L) of fuel into the Bayou Casotte stream.[12]

By late on July 19, the American Red Cross was providing shelter to over 2,000 people in Alabama, Mississippi, and Florida.[13]

Extreme amounts of rainfall were produced over Alabama.[2] Dauphin Island had the highest amount of rainfall, 37.75 in (959 mm) reported by the HPC.[14] Dauphin Island Sea Lab recorded 36.71 in (932 mm) of rain, but not all the rain may have recorded in the rain gauge at this location, so it is possible the rainfall may have been underestimated. Doppler weather radar estimates show that around 43 inches (1,100 mm) of rain fell off the coast of Dauphin Island. A storm surge of over 6.5 feet (2.0 m) occurred off Highway 182, midway between Gulf Shores and Fort Morgan, in addition to the rainfall. Unusually, when the storm stalled off the coast of Alabama, prevailing northerly winds forced the water out of Mobile Bay, causing tides to be two feet (0.61 m) below normal. Observers noted that, if river channels had not remained, it would have been possible to walk across the bay unhindered by water.[2] Additionally, a four-story condominium project that was under construction in Gulf Shores crashed due to high winds.[15] In addition, three tornadoes occurred in Alabama, destroying a marina just south of Orange Beach and damaging several of the boats; Opelika, where damage was minimal; and Alabama Port respectively.[2][16]

Despite its effects in the northern Gulf of Mexico, only one person was directly killed from the storm there; a man drowned off the coast when he fell off his sailboat near Fort Morgan, Alabama. One indirect casualty also occurred in the area, when a man had a heart attack while trying to secure a boat off the Alabama coast during the storm.[2] Numerous roads became flooded and impassable for several days, south and along I-10 in Mobile, south and central Choctaw, and Baldwin counties. Along the Fowl and Fish rivers, in Mobile and Baldwin counties respectively, significant damage to homes occurred due to flooding. Most roads on Dauphin Island were flooded in over a foot of water. A few homes were close to falling into Mobile Bay, and one home had to be moved backwards towards land to prevent its destruction.[17] At the peak of the storm in Alabama, at least 44,000 people were without power in Mobile and Baldwin counties. In rural Choctaw County, north of Mobile, several families were rescued from flooded roads and trapped cars.[9] The majority of houses and businesses on Dauphin Island and buildings from the western shore of Mobile Bay, and from Fort Morgan east to Orange Beach, had roof damage$. 60.5 million (1997 USD$, 115 million 2024 USD) in total property damage occurred in Alabama, in addition to pecan and pine tree damage costing $2.5 million (1997 USD$, 4.75 million 2024 USD).[17]

East Coast[edit]

In the state of Florida, some damage to the cotton crop occurred in Escambia County. Otherwise, very little damage resulted from the storm in northwestern Florida.[17] The Panama City, Florida area had some minor fresh water flooding.[8] A race in the NASCAR All Pro series at the Five Flags Speedway in Pensacola, Florida scheduled to be held on July 19 was postponed to September 13, 1997, due to Hurricane Danny.[18] By the time Danny reached Georgia and the Carolinas, its potential impact had weakened, though it still managed to produce 8–12 inches (200–300 mm) of rain as it drifted through the western portions of the states.[2] In Augusta, Georgia, fourteen South Carolina National Guardsmen were struck by lightning, one of whom had to be hospitalized in intensive care and six others received treatment at a hospital and were then released.[19] Four indirect deaths occurred from traffic accidents during the storm's onslaught in Georgia.[2] Seven tornadoes and one waterspout resulted in South Carolina due to Danny strengthening over the southern Appalachians.[20] Among those tornadoes, a severe thunderstorm cell in South Carolina produced five tornadoes which touched down, one of which killed a woman in her destroyed duplex while passing through Lexington County.[2] Additionally, a F2 tornado with a width of 200 yards (200 m) and a length of 4 miles (6 km), was on the ground for 3 miles (5 km) to the northeast of Gaston, South Carolina, causing $942,000 (1997 USD$, 1.79 million 2024 USD) in damage, killing one, injuring six, and destroying 13 residences, with damage to many others.[21] Several tornadoes and waterspouts were spawned over Virginia; most of them occurred in Norfolk, Portsmouth, and Hampton.[22] An F1 tornado with a width of 50 yards (50 m) and a length of 1-mile (1.6 km), touched down 1-mile (1.6 km) in Portsmouth, causing $400,000 (1997 USD$, 759,204 2024 USD) in damage. It destroyed a car wash and damaged 7 other structures, all but 1 of which were businesses, and also flipped over a semi-trailer truck.[23] Rainfall in Fayetteville measured 2.85 inches (72 mm), while the remainder of the Mid-Atlantic states received approximately 3 inches (76 mm) of rain.[24]

The heavy rains caused two people to drown in Charlotte. A girl drowned after being swept into a creek, and a woman drowned while in her car.[2] Also in North Carolina, tropical rains related to Danny caused a CSX train to derail from its trestle into Little Sugar Creek, spilling about 2,500 gallons (9,500 L) of diesel and therefore forcing a nearby public housing development to be evacuated.[25] After Danny emerged over the Atlantic Ocean on the North Carolina-Virginia border and restrengthened into a tropical storm on July 25, wind and rain started as far north as New York and New England.[26] Sustained tropical-storm force winds affected Martha's Vineyard, Nantucket Island, and parts of Cape Cod, in addition to the coastal waters from the entrance of Buzzards Bay to the south and east of Cape Cod. Only minor damage occurred, despite these strong winds, which were experienced primarily in southeastern Massachusetts.[8][27] The minor damage included localized flooding, power outages, downed tree limbs, and lost boats. A suspension of ferry service to Nantucket Island occurred for most of July 25, with a shorter suspension happening on the service to Martha's Vineyard. No significant coastal flooding affected the region, although a storm shelter was opened on Nantucket Island to host a Boy Scout group camping there. Danny was the fifth tropical cyclone to affect Southern New England in the 20th century during the month of July.[8]

Aftermath and records[edit]

On July 24, the U.S. House of Representatives considered House Amendment 271 to H.R. 2160 Agriculture, Rural Development, Food and Drug Administration, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, 1998, to eliminate federal support for crop insurance for tobacco farmers and disaster assistance provided to non-insured crops of tobacco. During debate of the amendment, Congressman Etheridge (D-NC) stated that one of the reasons he opposed it was due to the harm it would cause to farmers like those in his home state of North Carolina whose tobacco crops were being flooded by Danny. Other congressmen from his state including Richard Burr and Walter B. Jones Jr. also opposed it.[28] Ultimately, the vote on the amendment failed by a vote of 209 to 216 and it failed to be included in the bill that later became law.[29]

On July 25, President Clinton declared a major disaster in Alabama in the aftermath of Hurricane Danny. He ordered that federal aid be provided in assistance to state and local efforts to respond in the areas of Alabama impacted by wind and flooding damage.[30]

Debris remained in the inland waters of Alabama until at least August 12, 1997. Endangered or threatened sea turtles lived in these waters and were threatened by the debris. Specialized turtle exclusion devices, known as TEDs, or specialized nets that allowed the turtles to escape them, were required before Danny for shrimp trawlers. The Director of the Marine Resources Division of the Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources said that the "inordinate amount of debris is causing extraordinary difficulty with the performance of (TEDs) in these areas." Therefore, the United States Environmental Protection Agency allowed an alternative to the TEDs, of shorter tow times with seasonal restrictions of a maximum of 55 minutes from April 1 through October 31, and a maximum of 75 minutes from November 1 through March 31. By making the shorter tow times the required alternative, the EPA intended to minimize any sea turtle casualties as a result of trawlers being allowed to remove the TEDs.[31]

One of three wolves that escaped from a zoo in Gulf Shores, Alabama during Hurricane Danny was found in November later that year, after seasonal conditions meant less tourists and therefore less food in Gulf State Park where the wolf had resided. One of the other wolves had already been recaptured, while the other had already been shot and killed.[32]

Some cotton crops in the Southeast United States received needed rainfall from Danny, while others were harmed, as 100,000 acres of cotton fields in Alabama were too heavily damaged for their crop to be salvaged.[33] The effects of Danny caused the gasoline production of Gulf Coast oil refineries to decline and thus contributed to an increase in gas prices in the months following Danny throughout the United States.[34] A severe drought had been in place in the Mid-Atlantic region during the month of July.[8] The high amount of rainfall caused by Danny helped to ease dry conditions in portions of the Mid-Atlantic, but not sufficiently to stop the drought from developing further in most areas from northern Virginia to southern New England.[35]

A study published in Social Behavior and Personality in 1998 surveyed respondents from the University of West Florida and businesses in Pensacola for the news media sources they relied on during Hurricane Danny. Overall, the frequency of usage from highest to lowest among respondents was local TV stations, the cable network Weather Channel, local FM radio stations, cable news stations, and followed by other sources.[36]

The extremely short distance of the eyewall of Hurricane Danny from a Doppler weather radar station in Mobile, Alabama and its slow landfall over the course of a day led to further study by meteorologists. The proximity to land allowed for measurements at a level closer to the surface than it is possible for hurricane reconnaissance aircraft to achieve, with the slow landfall allowing for more extended observation. One conclusion of the study, published in 2000, included the need to sample the boundaries of an eyewall more to establish a better estimate of surface-level winds and the overall intensity of a storm. Another conclusion was that while Danny's slow movement positioned it over a tidal estuary bordering the Gulf, maintaining of or increase in strength was possible since eyewall convection remained over waters with high sea surface temperatures and other environmental conditions remained favorable.[37]

The storm dropped 36.71 in (932 mm) of rain on Dauphin Island, setting the new record for the most tropical or subtropical cyclone related rainfall in the state of Alabama, and is among the largest in the United States.[2]

See also[edit]

- Other storms of the same name

- List of New England hurricanes

- List of New Jersey hurricanes

- List of Delaware hurricanes

- List of wettest tropical cyclones in Alabama

- List of North Carolina hurricanes (1980–1999)

- Hurricane Hermine (2016) – A hurricane of similar intensity and path

- Hurricane Sally (2020) – Also stalled just offshore of Alabama

References[edit]

- ^ a b Rappaport, Edward N. (1999). "Atlantic Hurricane Season of 1997". Monthly Weather Review. 127 (9): 2012. Bibcode:1999MWRv..127.2012R. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1999)127<2012:AHSO>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 1520-0493.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Pasch, Richard J (August 21, 1997). Preliminary Report: Hurricane Danny (PDF) (Report). United States National Hurricane Center. Retrieved February 27, 2023.

- ^ Robert E. Hart; Jenni L. Evans (2001). "A Climatology of the Extratropical Transition of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones" (PDF). Journal of Climate. 14 (4): 546–564. Bibcode:2001JCli...14..546H. doi:10.1175/1520-0442(2001)014<0546:ACOTET>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved December 14, 2007.

- ^ Valerie Voss; Charles Zewe (1997). "Hurricane Danny skims Louisiana tip, moves northeast". CNN. Reuters. Archived from the original on June 17, 2006. Retrieved December 28, 2006. Accessed via the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b c "Hurricane Danny heading for Alabama and Mississippi". CNN. Associated Press, Reuters. 1997. Archived from the original on June 20, 2006. Retrieved December 29, 2006. Accessed via the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Hurricane Danny Crawls Along Southern Coastline". Washington Post. July 19, 1997. Retrieved September 30, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e NCDC (1997). "Event Record Details: Hurricane (Louisiana)". National Climatic Data Center. Archived from the original on October 1, 2008. Retrieved January 1, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f National Weather Service (September 10, 1997). "Hurricane Danny damage reports". USA Today. Archived from the original on March 9, 2000. Retrieved February 4, 2007.

- ^ a b Charles Zewe (1997). "Danny drifts north, leaving mayhem in its wake". CNN. Associated Press. Archived from the original on February 12, 2005. Retrieved December 31, 2006. Accessed via the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Barry D. Keim; Robert A. Muller (2009). Hurricanes of the Gulf of Mexico. Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 9780807136676. Retrieved May 3, 2013.

- ^ NCDC (1997). "Event Record Details: Hurricane (Mississippi)". National Climatic Data Center. Archived from the original on October 1, 2008. Retrieved January 1, 2007.

- ^ Saunders, Jessica (1997). "Some Remain on Alabama Coast as Danny Bears Down". Associated Press News. Retrieved April 27, 2013.

- ^ Jessica Saunders (1997). "Hurricane Danny Downgraded to Tropical Storm". Associated Press. Retrieved April 27, 2013.

- ^ Roth, David M (1997). "Hurricane Danny - July 14-28, 1997". United States Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved February 25, 2023.

- ^ Jessica Saunders (1997). "Now a Tropical Storm, Danny Lingers Over Alabama". Associated Press. Retrieved April 27, 2013.

- ^ NWS-Birmingham Internet Services Team (2006). "NWS-Birmingham Internet Services Team". National Weather Service. Archived from the original on October 10, 2006. Retrieved December 31, 2006.

- ^ a b c NCDC (1997). "Event Record Details: Hurricane (Alabama)". National Climatic Data Center. Archived from the original on October 1, 2008. Retrieved January 1, 2007.

- ^ David Poole (September 10, 1997). "Martin Muscles His Way to Finish". Charlotte Observer.

- ^ "Hurricane Remnants Cause Outages in North Carolina; Heat in the Planes". Associated Press. 1997. Retrieved April 27, 2013.

- ^ Edwards, Roger (1999). "Tornado Production by Exiting Tropical Cyclones". Storm Prediction Center. Retrieved November 21, 2018.

- ^ NCDC (1997). "Event Record Details: Tornado 307724 (Virginia)". National Climatic Data Center. Archived from the original on October 1, 2008. Retrieved January 1, 2007.

- ^ National Weather Service (1997). "Local Sightings of Tornadoes and Funnel Clouds". Virginian Pilot. Archived from the original on May 16, 2005. Retrieved December 28, 2006.

- ^ NCDC (1997). "Event Record Details: Tornado 313574 (Virginia)". National Climatic Data Center. Archived from the original on October 1, 2008. Retrieved January 1, 2007.

- ^ Neal Lott; Doug Ross; Axel Graumann; Tom Ross (1997). "Hurricane Danny". NCDC. Archived from the original on April 3, 2012. Retrieved December 28, 2006.

- ^ Paul Nowell (1997). "Danny Just Won't Give Up: Flooding Prompts Evacuations in N.C., Georgia". Associated Press. Retrieved April 27, 2013.

- ^ "Remnants of Hurricane Danny Bring Havoc to North Carolina". New York Times. Associated Press. July 25, 1997. Retrieved September 30, 2018.

- ^ "Tropical Storm Danny Visits Portsmouth!". 1997. Archived from the original on October 22, 2002. Retrieved December 28, 2006.

- ^ "Congressional Record - House, Vol. 143 No. 106" (PDF). Library of Congress. July 24, 1997. pp. 25–33. Retrieved September 30, 2018.

- ^ "H.Amdt.271 to H.R.2160". Library of Congress. July 24, 1997. Retrieved September 30, 2018.

- ^ Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States, William J. Clinton, 1997, Book 2, July 1 to December 31, 1997. Government Printing Office. 1999. ISBN 9780160499852. Retrieved September 30, 2018.

- ^ National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (1997). "Sea Turtle Conservation; Shrimp Trawling Requirements". United States Environmental Protection Agency. Archived from the original on September 1, 2009. Retrieved December 29, 2006.

- ^ "Zoo Wolf that Escaped During Hurricane Led Safely Home". Associated Press. 1997. Retrieved April 27, 2013.

- ^ Curt Anderson (1997). "Corn Crops Looking Good, Wheat Up, Corn Down". Altus (OK) Times. Associated Press. Retrieved April 27, 2013.

- ^ "Despite Cut In Gas Tax, Price at Pump Rises Sharply". New York Times. 1997. Retrieved April 27, 2013.

- ^ USDA (1997). "Crop Production". Cornell University. Archived from the original on August 19, 2014. Retrieved April 27, 2013.

- ^ Piotrowski, Chris; Armstrong, Terry R. (1998). "Mass Media Preferences in Disaster: A Study of Hurricane Danny". Social Behavior and Personality. 26 (4): e946. doi:10.2224/sbp.1998.26.4.341.

- ^ Keith G. Blackwell (2000). "Monthly Weather Review: The Evolution of Hurricane Danny (1997) at Landfall: Doppler-Observed Eyewall Replacement, Vortex Contraction/Intensification, and Low-Level Wind Maxima". Monthly Weather Review. 129. American Meteorological Society: 4002. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(2000)129<4002:TEOHDA>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 1520-0493. Retrieved May 3, 2013.

External links[edit]

- 1997 Atlantic hurricane season

- Category 1 Atlantic hurricanes

- Hurricanes in Louisiana

- Hurricanes in Mississippi

- Hurricanes in Alabama

- Hurricanes in Tennessee

- Hurricanes in Florida

- Hurricanes in Georgia (U.S. state)

- Hurricanes in North Carolina

- Hurricanes in South Carolina

- Hurricanes in Virginia

- Hurricanes in Massachusetts

- 1997 natural disasters in the United States