Martyn Finlay

Martyn Finlay | |

|---|---|

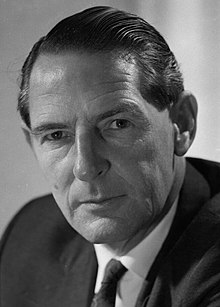

Finlay in 1968 | |

| 23rd Attorney-General | |

| In office 8 December 1972 – 12 December 1975 | |

| Prime Minister | Norman Kirk Bill Rowling |

| Preceded by | Roy Jack |

| Succeeded by | Peter Wilkinson |

| 36th Minister of Justice | |

| In office 8 December 1972 – 12 December 1975 | |

| Prime Minister | Norman Kirk Bill Rowling |

| Preceded by | Roy Jack |

| Succeeded by | David Thomson |

| 8th Minister of Civil Aviation and Meteorological Services | |

| In office 8 December 1972 – 12 December 1975 | |

| Prime Minister | Norman Kirk Bill Rowling |

| Preceded by | Peter Gordon |

| Succeeded by | Colin McLachlan |

| Member of the New Zealand Parliament for Henderson Waitakere (1963–1969) | |

| In office 30 November 1963 – 25 November 1978 | |

| Preceded by | Rex Mason |

| Succeeded by | Ralph Maxwell |

| 19th President of the Labour Party | |

| In office 8 June 1960 – 12 May 1964 | |

| Vice President | Jim Bateman |

| Preceded by | Mick Moohan |

| Succeeded by | Norman Kirk |

| Member of the New Zealand Parliament for North Shore | |

| In office 30 November 1949 – 1 September 1951 | |

| Preceded by | New constituency |

| Succeeded by | Dean Eyre |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1 January 1912 Dunedin, New Zealand |

| Died | 20 January 1999 (aged 87) Auckland, New Zealand |

| Political party | Labour Party |

| Spouse | Zelda May Finlay |

| Children | 3 |

| Alma mater | University of Otago |

| Profession | Lawyer |

Allan "Martyn" Finlay QC (1 January 1912 – 20 January 1999) was a New Zealand lawyer and politician of the Labour Party. He was an MP in two separate spells and a member of two different governments, including being a minister in the latter where he reformed the country's justice system.

Biography[edit]

Early life[edit]

Martyn was born in Dunedin to Baptist missionaries who had worked in India. His father died when he was two and his mother was forced by economic circumstances to take in boarders. He used to push his brother Harold, ten years older and with polio, two miles to Otago University in his wheelchair. With the oncoming depression, Martyn had to leave school to get a job at the end of fifth form - he had wanted to be a doctor. With a job as an office boy in a law firm at the age of 16, he was able to study law part-time at Otago University for eight years before getting his LLM with First Class Honours.[1] In 1934 he was the winner of the Otago University Law Society's prize in evidence.[2]

He got a scholarship to the London School of Economics and got a PhD in 1938 before becoming a Resident Fellow at Harvard. He met many influential intellectuals in London including Harold Laski, who encouraged him to enter politics.[3] He returned to NZ in 1939 and was employed as a private secretary to Cabinet Ministers Rex Mason and Arnold Nordmeyer.[4] Finlay was impressed by Mason's mastery of the legal system and was impressed that he devised and drafted almost all of his legislation himself.[3]

Political career[edit]

| Years | Term | Electorate | Party | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1946–1949 | 28th | North Shore | Labour | ||

| 1963–1966 | 34th | Waitakere | Labour | ||

| 1966–1969 | 35th | Waitakere | Labour | ||

| 1969–1972 | 36th | Henderson | Labour | ||

| 1972–1975 | 37th | Henderson | Labour | ||

| 1975–1978 | 38th | Henderson | Labour | ||

Martyn Finlay stood unsuccessfully for Remuera in 1943. He then represented the North Shore electorate from 1946 to 1949, when he was defeated. Finlay frequently challenged Prime Minister Peter Fraser in caucus over issues such as compulsory military training, earning him the ire of the party establishment. After his defeat neither Fraser nor his successor as leader Walter Nash gave Finlay any assistance in returning to parliament because of his rebelliousness.[5] He stood for the Labour nomination at the 1953 Onehunga by-election but lost out to the comparatively inexperienced candidate Hugh Watt.[6] In later years Finlay frequently described himself and fellow Labour MP Warren Freer as the "only remnants" of the first Labour government, a government of whose record he was proud of stating "It was a government of very practical talents. If they saw people hungry, they knew hunger came from malnutrition and that malnutrition came from lack of money, in turn due to lack of a job. They knew nothing of such concepts as level playing fields. And they did not have the help of economists."[7] Despite his disagreements with Fraser, he spoke fondly of him when reminiscing. In 1977 he said Fraser was a statesman of the highest order whose qualities few New Zealanders fully appreciated.[3]

Between his spells in parliament he was Vice-President of the Labour Party from 1955 to 1960 and subsequently President from 1960 to 1964.[8] From 1957 to 1960 he was a director of Tasman Empire Airways.[3]

As party president Finlay was highly critical of the lack of drive in the party, feeling Labour should take the offensive over industrialization rather than sit about and answer criticisms as National made them. He primarily thought the retirement of Nash as leader would be the remedy and after Labour returned to opposition after the 1960 election he began pressing for Nash to resign. In October 1961 he gave notice of motion to the national executive that the caucus should be asked to consider the leadership. In February 1962 Finlay withdrew his notice of motion after Nash met with the national executive. By June Nash told Finlay and the caucus that be would resign at the end of the year unless caucus requested otherwise. However by December Nash had still made no move to resign and Finlay penned a statement to the members of caucus, including Nash, bluntly requesting Nash's retirement from the leadership. Finlay was criticised for the letter itself and the manner of its presentation, as instead of attending caucus and presenting it himself, he went to Auckland to appear in court, and left it to Jim Collins (a trade union member of the executive) to read it to the caucus on his behalf on 6 December. At the beginning of the meeting Nash told caucus that he would resign at a caucus meeting in February and would not be a candidate for re-election. Only after which Collins then read Finlay's letter. The letter caused a stir in the caucus and it was resolved unanimously that the letter be not received.[9]

Later he represented the Waitakere electorate from 1963 to 1969, then the Henderson electorate from 1969 to 1978, when he retired.[10] Soon after re-entering parliament he was designated Labour's Justice Spokesperson.[11] By the time he re-entered parliament Nash had retired from the leadership and been replaced by Arnold Nordmeyer. Finlay though highly of Nordmeyer and his abilities, but thought he was too isolated from his colleagues to be a successful leader. He still felt Nordmeyer was treated unfairly when he was toppled as leader by Norman Kirk.[3]

Vietnam War[edit]

Martyn Finlay was also one of the Labour Party's most active opponents of New Zealand's military involvement in the Vietnam War and questioned the New Zealand government's support for South Vietnam. In 1964, he argued during a parliamentary speech that the Viet Cong were the only effective opposition in South Vietnam, but still accepted the general consensus within New Zealand government circles that the Viet Cong were being supported by North Vietnam and the People's Republic of China.[12] On 6 June 1965, Finlay chaired an anti-war meeting in Auckland which was sponsored by the Auckland Trades Council, the Auckland Labour Representation Committee, and the Auckland Peace For Vietnam Committee (PFVC). A prominent speaker at that meeting was the trade unionist Jim Knox.[13] He also participated in a teach-in at the University of Auckland on 12 September 1966, which drew about 600 people.[14]

During a Labour Party conference in 1966, Martyn Finlay, at the instigation of the Labour Party leader and future Prime Minister Norman Kirk, proposed an amendment which advocated replacing New Zealand's artillery battery with a non-combatant force.[15] Despite his opposition to the Vietnam War, Finlay argued that New Zealand troops should not be withdrawn from Vietnam too quickly to avoid interfering with the Paris peace talks in 1969.[16] Later, he lost a notable 1969 election TV debate (on the NZBC's Gallery programme) against Robert Muldoon. When the United States Vice President Spiro Agnew visited the capital Wellington in mid-January 1970, Finlay along with several other Labour Members of Parliament including Arthur Faulkner, Jonathan Hunt, and Bob Tizard boycotted the state dinner to protest American policy in Vietnam. However, other Labour MPs including the Opposition Leader Norman Kirk attended the function which dealt with the Nixon Doctrine.[17]

Cabinet Minister[edit]

Finlay was a Cabinet Minister, and was the Attorney-General, Minister of Justice and Minister of Civil Aviation and Meteorological Services from 1972 to 1975 in the Third Labour Government.[18][19] 11 years later he publicly recalled frustrations felt by the government in trying to put changes in policy into practice immediately following the election which, in Finlay's view, stemmed from a lack of positive cooperation from senior public servants who were biased to the National Party.[20] Finlay established the small claims court where "people owed $10 can be heard without having to pay a lawyer $30" and also established duty solicitors to look after the interests of poor people charged in court.[7]

He was made a Queen's Counsel (QC) in 1973.[21] The same year he was a member of the legal team that represented the New Zealand and Australian government at the International Court of Justice in an attempt to ban French nuclear tests in the Pacific.[22] Finlay attracted world-wide attention with his performance leading the New Zealand team at the World Court in the joint New Zealand-Australia case seeking a ban on French nuclear testing at Mururoa Atoll. He said later "Ours was a much better case than the Australians and better received by the court," and eventually the court ruled it would be unlawful for France to continue atmospheric testing.[7] After Kirk's sudden death Finlay was speculated in the media as a possible leadership contender.[23] While he gave serious consideration to standing ultimately he did not stand.

He set up the Disputes Tribunal and was responsible for much of the work leading to the Matrimonial Property Act which would give divorced wives a right to share in their husband's possessions.[8] He also ended bread-and-water punishments in prisons and bestowed prisoners the right to write directly to the Minister of Justice without having their correspondence read prior by prison staff. Finlay also abolished a husband's right to sue his wife's lover for damages removing one of the last legal stipulations of a wife being deemed her husband's property.[7] While proud of his legal reforms he was disappointed that he could not do more.[3]

After Labour's shock defeat in 1975 Finlay remained on the frontbench as Shadow Minister of Justice and Shadow Attorney-General until deciding to retire at the next election which saw his seat redistricted.[24] He was the recipient of a harsh verbal attack from then prime minister Robert Muldoon in 1977. Muldoon said he despised Finlay, and the sooner the retiring MP was out of the house the better. However, in a rare move, Muldoon later apologised publicly for the outburst, stating that he had misunderstood the situation.[20] Prior to announcing his retirement it was speculated in 1976 that he would leave parliament mid-term to cause a by-election which Labour would use to test public mood ahead of the general election.[3]

Later life[edit]

After leaving parliament he practiced law full-time as a Queen's Counsel. He was appointed by the government to investigate two industrial relations disputes; in 1984 during a railway workers' dispute in Picton and in 1985 during a refinery expansion in Whangārei. He retired in 1988.[4]

In 1983 his daughter Sarah Jane was sentenced to nine months' imprisonment on charges of supplying and possessing heroin. In 1989 she was found dead in her Wellington flat.[20]

Finlay often weighed in on political issues after his exit from parliament. He was particularly critical of the economic restructuring (known as Rogernomics) by the Fourth Labour Government in the 1980s.[20]

Death[edit]

Martyn died at the age of 87. Christine Cole Catley says: "He wrote two most moving letters to his wife, a year apart. She read them for the first time after he died … He wrote of what he saw as his degeneration and his fear of becoming a burden on her and others. ... Two days later he ended his life."[25]

He was survived by his wife, son and daughter.[20]

Personal views[edit]

Finlay's socially liberal views were said to have put him ahead of his time, especially on moral issues such as legalizing homosexuality and granting name suppression in court unless people were convicted.[20] He was also an advocate for abortion during the 1970s, but did not find widespread support, though he won favour from younger generations.[8]

Parliamentary colleague Michael Bassett has said Finlay was "essentially a man of peace throughout his life" who "found Peter Fraser's crusade to introduce Compulsory Military Training personally distasteful."[26] Bassett also said: "To his dying day Finlay was an opponent of capital punishment, a cause to which he added divorce law reform (his own divorce in the 1950s was particularly fraught), homosexual, and abortion law reform. Finlay’s reputation as an advanced liberal on social issues attracted the support of younger party idealists as much as it repelled Labour's more conservative wing, especially Catholics. Finlay’s marital complications irked the puritanical Walter Nash, who did nothing to advance his return to Parliament, and seems not to have welcomed his election as party president in 1960."[26]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Holman & Cole Catley 2004, p. 196.

- ^ "University Year - Graduation Ceremony". Otago Daily Times. No. 22263. 16 May 1934. p. 7. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g Lockstone, Brian (28 May 1977). "Finlay leaves disillusioned". Auckland Star. p. 4.

- ^ a b "Martyn Finlay QC, 1912 - 1999". New Zealand Law Society. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ^ Hobbs 1967, pp. 108.

- ^ "Onehunga Seat - Choice of Labour Candidate". The Press. Vol. LXXXIX, no. 27199. 17 November 1953. p. 10.

- ^ a b c d Potter, Tony (24 January 1999). "Finlay's was a rare voice of reason and justice". Sunday Star-Times. p. A9.

- ^ a b c "Labour intellectual who had ideas ahead of his time dies". The Press. 22 January 1999. p. 8.

- ^ Sinclair 1976, pp. 354–357.

- ^ Wilson 1985, p. 196.

- ^ Grant 2014, pp. 152.

- ^ Rabel 2005, p. 76-78.

- ^ Rabel 2005, p. 120.

- ^ Rabel 2005, p. 162.

- ^ Rabel 2005, p. 180.

- ^ Rabel 2005, p. 287.

- ^ Rabel 2005, pp. 299–300.

- ^ "Obituary—Hon. Dr Allan Martyn Finlay QC". New Zealand Hansard. VDIG.net. 16 February 1999. Retrieved 29 August 2013.

- ^ Wilson 1985, pp. 92–93.

- ^ a b c d e f "Labour intellect Finlay dies". The Dominion. 22 January 1999. p. 2.

- ^ "Queen's Counsel appointments since 1907 as at July 2013" (PDF). Crown Law Office. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 March 2014. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- ^ Alley, Rod (20 June 2012). "Multilateral organisations - Rule-making: maritime, environmental and criminal". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- ^ "Caucus Will Choose New Leader". The New Zealand Herald. 2 September 1974. p. 1.

- ^ "Surprises Among Party Spokesmen". The New Zealand Herald. 30 January 1976. p. 10.

- ^ Holman & Cole Catley 2004, p. 204.

- ^ a b Bassett, Michael. "Hon Dr Allen Martyn Finlay (1912-1999)". Dr Michael Bassett. Archived from the original on 22 January 2016. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

References[edit]

- Grant, David (2014). The Mighty Totara: The life and times of Norman Kirk. Auckland: Random House. ISBN 9781775535799.

- Hobbs, Leslie (1967). The Thirty-Year Wonders. Christchurch: Whitcombe and Tombs.

- Holman, Dinah; Cole Catley, Christine, eds. (2004). Fairburn and Friends. North Shore City: Cape Catley Ltd.

- Rabel, Roberto (2005). New Zealand and the Vietnam War: Politics and Diplomacy. Auckland: Auckland University Press. ISBN 1-86940-340-1.

- Sinclair, Keith (1976). Walter Nash. Auckland: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-647949-5.

- Wilson, James Oakley (1985) [First ed. published 1913]. New Zealand Parliamentary Record, 1840–1984 (4th ed.). Wellington: V.R. Ward, Govt. Printer. OCLC 154283103.

- 1912 births

- 1999 deaths

- New Zealand Labour Party MPs

- Members of the Cabinet of New Zealand

- 20th-century New Zealand lawyers

- Members of the New Zealand House of Representatives

- New Zealand MPs for Auckland electorates

- New Zealand King's Counsel

- Attorneys-General of New Zealand

- Unsuccessful candidates in the 1949 New Zealand general election

- Unsuccessful candidates in the 1943 New Zealand general election

- 1999 suicides

- Suicides in New Zealand

- Justice ministers of New Zealand