Melville Monument

| |

| |

| 55°57′15″N 3°11′35″W / 55.95423°N 3.19315°W | |

| Location | St Andrew Square, Edinburgh, Scotland, United Kingdom |

|---|---|

| Designer | William Burn (architect) Francis Leggatt Chantrey (statue) |

| Type | Victory column |

| Material | Sandstone |

| Height | 45 m (150 ft) |

| Weight | approx. 1,500 tons[1] |

| Beginning date | 1821 |

| Completion date | 1827 |

| Restored date | 2008 |

| Dedicated to | Henry Dundas, 1st Viscount Melville |

Listed Building – Category A | |

| Official name | St Andrew Square, Melville Monument with Boundary Walls and Railings |

| Designated | 13 January 1966 |

| Reference no. | LB27816 |

The Melville Monument is a large column in St Andrew Square, Edinburgh constructed between 1821 and 1827 as a memorial to Scottish statesman Henry Dundas, 1st Viscount Melville.

Dundas, the most prominent politician from Scotland of his period, was a dominant figure in British politics during much of the late 18th century. Plans to construct a memorial to him began soon after his death in 1811 and were largely driven by Royal Navy officers, especially Sir William Johnstone Hope. After a successful campaign for subscriptions, construction of the monument began in 1821 but time and costs soon spiralled out of control. The project was not completed until 1827 and not paid off until 1837. During the 21st century, the monument became the subject of increasing controversy due to Dundas' legacy, especially debates over the extent of his role in legislating delays to the abolition of British involvement in the Atlantic slave trade.[2] In the wake of protests following the murder of George Floyd in 2020, the City of Edinburgh Council moved to erect a plaque on the monument to reflect the Dundas' legacy[3] according to the Edinburgh Slavery and Colonialism Legacy Review Report and Recommendations.[4] Installation of the plaque was completed in October 2021.In March 2023 the City of Edinburgh Council planning committee voted to remove the contentious plaque [5] but the council later explained that it did not intend to remove the plaque.[6]

Designed by William Burn, the column is modelled after Trajan's Column in Rome. Robert Stevenson provided additional engineering advice during construction. The column is topped by a 4.2 m (14 ft) tall statue of Dundas designed by Francis Leggatt Chantrey and carved by Robert Forrest. The total height of the monument is about 45 m (150 ft). It is one of Edinburgh's most prominent landmarks.[2]

History[edit]

Henry Dundas, 1st Viscount Melville[edit]

Dundas was born on 28 April 1742 at Arniston House, Midlothian to one of Scotland's most distinguished legal families. After studying at the University of Edinburgh and practising as an advocate, he first entered parliament in 1774.[7] The following year, Dundas became Lord Advocate and arrogated immense power over Scottish affairs to the office. He also took an interest in the welfare of the Highlands, repealing the Disarming Act in 1781 and founding the Highland Society in 1784. Having tried to prevent widespread electoral manipulation, he abandoned these efforts and instead used such practices to his own ends. By 1796, he had effective control of all but two of Scotland's members of parliament.[8]

Dundas gained influence under Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger and soon became Home Secretary: in this role, he suppressed popular unrest during the French Revolution.[9] After France declared war on Britain in 1793, during the French Revolutionary Wars, he supported consolidation of the empire and the union of Great Britain with Ireland alongside Catholic emancipation.[10]

In the Commons, Dundas opposed William Wilberforce's legislative efforts to abolish the slave trade "immediately." He proposed a gradual method that would wind down slavery and the slave trade together, with the slave trade ending by 1800, and while he had some support among abolitionists, Wilberforce and other hardliners opposed his plan, and the West Indian slave interests were also against him.[11] The hardliners amended his plan to have the slave trade end in 1796, but were thwarted by the House of Lords, who refused to consider it.

As First Lord of the Admiralty, he led the strengthening of the Royal Navy in the period before the Battle of Trafalgar. Having been ennobled as Viscount Melville in 1802, Dundas was impeached for misappropriation of naval funds and tried by the House of Lords. Dundas was found not guilty on all charges and re-entered the Privy Council. He died in Edinburgh on 27 May 1811.[12]

Moves to commemorate Dundas[edit]

In 1812, Dundas' supporters raised a large obelisk to his memory on his Dunira estate near Comrie, Perthshire.[13] At the same time, Dundas' family, with support from subscribers among the public, supported the creation of a monument to Dundas in Edinburgh. The result was the marble statue by Francis Leggatt Chantrey in Parliament Hall, completed in 1818.[14] The existence of this memorial later led some to question the relevance of the St Andrew Square project. In March 1821, shortly before construction began, a correspondent in The Scotsman, a Whig newspaper, argued the existence of this statue made another memorial to the same figure in the same city irrelevant.[15]

The idea of another monument to Dundas in Edinburgh was first raised at a meeting of the Pitt Club of Scotland in May 1814.[16] This may have motivated Vice Admiral Sir William Johnstone Hope to initiate a movement for such a monument within the Royal Navy. Hope started the Melville Monument Committee, of which he was convener.[17] In government, Dundas had become known as the "Seaman's Friend" for his advancement of measures to support sailors of the Royal Navy and their dependents.[18][19] In its initial stages, the project was both led by naval officers and supported exclusively by subscriptions from sailors; although civic and legal figures were represented on the committee.[a] Alongside this primarily naval impetus for the monument, The Scotsman noted strong support from Dundas' own family.[15][21]

Development[edit]

The form and location of the monument were not initially settled and Hope first successfully applied to the town council for a site at the north east edge of Calton Hill. A correspondent in the Caledonian Mercury opposed the Calton Hill site, instead proposing the monument could be built on Arthur's Seat.[21] Further suggestions included Picardy Place or, nearby, the top of Leith Walk.[22] By the end of 1818, the committee appeared to have settled on St Andrew Square at the eastern end of Edinburgh's New Town.[21] Around this time, William Burn – an architect sympathetic to Dundas' Tory politics – appears to have been engaged. The form of a column modelled after Trajan's Column was agreed; though Burn's initial plan did not include a statue. The proprietors of the square agreed to the scheme by April 1819.[17][23]

In February 1820, the committee announced it was abandoning St Andrew Square in favour a site at the intersection of Melville Street and what is now Walker Street in the West End.[b] At the time, this was an under-developed site on the private property of Sir Patrick Walker outside the boundaries of the city. The committee had been negotiating with Walker since December 1818 but soon after the announcement, many on the committee balked at Walker's insistence that he and his descendants would maintain the monument. This entanglement with a private landowner, they feared, would undermine the monument's public character.[25][26]

The proprietors of St Andrew Square responded by renegotiating the contract for the monument. They offered the site free of charge while the city council agreed to maintain the structure. The contract was agreed in January 1821 and St Andrew Square was finally settled as the site of the monument.[27][28] The town council also agreed to accept responsibility for the monument on its completion. William Armstrong was engaged as builder at an agreed cost of £3,192: well within the £3,430 6s 4d the committee had raised. On 28 April 1821, the anniversary of Dundas' birth, Admirals Otway and Milne laid the foundation stone and a time capsule was sealed into the structure; George Baird, Principal of the University of Edinburgh said prayers as part of the ceremony. The day concluded with a celebratory dinner at the Warterloo Tavern.[29][30]

Construction[edit]

Soon after the contract was signed, Patrick Walker attempted to sue the committee for "breach of engagement" and claim damages of £10,000. In the end, the committee settled for £408, effectively tipping the project into debt.[28][31] Debt and delay grew, especially after an assessment by Robert Stevenson recommend strengthening the foundations and constructing the shaft from solid blocks rather than rubble infill as Burn had proposed.[32] These changes added £1,000 to the overall cost.[33] Stevenson's assessment was offered free of charge and had been spurred by the square's residents, many of whom were fearful of the stability of such a large monument.[34][35] Despite these problems, the committee persevered and, in 1822, agreed to include a statue, designed by Francis Leggatt Chantrey and carved by Robert Forrest.[36]

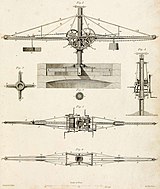

At Stevenson's suggestion, J. & J. Rutherford constructed the column using an iron balance crane such as Stevenson had employed during the construction of the Bell Rock Lighthouse.[1][37] The column, without its statue, was almost complete by the visit of George IV to Edinburgh in August 1822.[34] By August 1824, the statue was under construction at Forrest's workshop near Lesmahagow. In summer 1827, the sculpture was erected at the top of the monument, having been brought from Forrest's workshop in twelve carts and pulled up, block-by-block, via pulleys on an external scaffold. The face was the last block to be installed; beforehand, it had been stored for display in a wooden case in the gardens.[38][39]

Before and after the monument's completion, the committee's strong connections with the Royal Navy had made it reluctant to canvass public support to pay off the project's massive debts. In summer 1826, requests for support were therefore sent round every ship in the Navy. The Scotsman and The Times condemned the appeal, arguing it exploited impecunious junior seamen.[40] In February 1827, the committee finally made an appeal for public support. By April 1834, this and appeals to the Pitt Club had failed to reduce the debt below £1,100. The committee decided to require each of its own members to pay £41 13s 4d under threat of legal action. In the end, this too proved ineffective and only by 1837 were the final costs were paid by six remaining naval officers on a sub-committee.[41][42] The ultimate cost of the monument was £8,000.[43]

Initial reception and interpretation[edit]

Reappraisal of Dundas' legacy had begun soon after his death in 1811. Dundas' younger contemporary, the Whig lawyer Henry Cockburn, called Dundas "the absolute dictator of Scotland" for his domination of the country's patronage networks.[44] The monument's lengthy construction coincided with a period in which Dundas' legacy became more divisive. By the early 1830s, debates over the extension of the franchise dominated Edinburgh's politics while Dundas came to represent a repressive Tory administration.[45] In that decade, the town council recorded the complaints of citizens who objected to the city's maintenance of a memorial to an "unpopular" figure whose policies were "unwise and offensive".[45] Another contemporary, Thomas Babington Macaulay, praised the monument while damning its subject. In a letter of 1828, he wrote: "There is a new pillar to the memory of Lord Melville; very elegant, and very much better than the man deserved. [...] It is impossible to look at it without being reminded of the fate which the original most richly merited."[46]

At its erection, the Caledonian Mercury negatively compared the monument with similar recent structures, Lord Hill's Column at Shrewsbury and the Britannia Monument at Great Yarmouth. The newspaper claimed these monuments, lacking the reliefs that decorate the shaft of Trajan's Column, appeared "tottering and insecure" while the Melville Monument appeared "rather the remains of an edifice, than an entire object".[20] Despite these criticisms and controversies over Dundas' legacy, Connie Byrom assesses most contemporary reactions to the column's appearance to be positive.[39]

C.G. Desmarest argues the monument is "imperial in character and context": part of a general movement around the turn of the nineteenth century to honour heroes of Britain's empire. Desmarest cites the Nelson Monument, the National Monument and Chantrey's own statue of Pitt the Younger on George Street among other examples of this trend in Edinburgh.[47] Memorials of this time in Scotland often depict figures from the arts or from distant history. Such figures express "antiquarian nationalism" and "Unionist nationalism", which assert Scotland's unique national identity without challenging its place within the United Kingdom. In this context, Dundas represented, in Desmarest's words: "... a defender of the notion that Scotland was not a colony, but an equal partner in the Union".[48]

Subsequent history[edit]

On 14 July 1837, lightning stuck the monument. The committee remained unable to pay both the cost of repairs and the cost of a protective railing, which had been installed round the base of the monument in 1833.[49] These railings, within whose bounds the square's gardeners kept their equipment, had been removed by 1947.[50]

The monument has been protected as a Category A listed building since 1966.[2] In 2003, the Institution of Civil Engineers placed an explanatory plaque to the monument at the western entrance to the garden[c] and, in 2008, Edinburgh World Heritage supported the conservation of the monument as part of its Twelve Monuments scheme. The restoration coincided with a £2.4m refurbishment of St Andrew Square. The refurbishment concluded with the opening of the square for full public access for the first time in its history.[24][52] Restoration of the statue proved especially difficult; a special scaffold was constructed around the top of the monument.[53]

21st-century controversy[edit]

In 2017, the city council, responding to a petition from environmental campaigner, Adam Ramsay, convened a committee to draft the wording of a new plaque to reflect controversial aspects of Dundas' legacy, including his role in the delay in the abolition of the slave trade. The committee included academic and anti-racism campaigner Sir Geoff Palmer. The committee also included historian Michael Fry, who argued that, by arguing for "gradual" abolition, Dundas was taking a pragmatic approach to support abolition in a pro-slavery parliament.[d] Although the council aimed to install a new plaque by September 2018, the committee's work remained incomplete by 2020.[55][56]

In early June 2020, Palmer, responding to the international outcry over the murder of George Floyd, reiterated calls for a new plaque.[56] At this time, activity around the monument included graffiti on the pedestal and a petition to remove the monument altogether.[57] While a permanent plaque awaited planning, the council installed temporary plaques in July 2020. These bore the intended wording of the permanent plaque, which had been drafted by a sub-committee including representatives of the council and Edinburgh World Heritage along with Palmer.[58] In response, historian Sir Tom Devine criticised the council's decision-making process as a "kangaroo court". He argued Dundas had been "scapegoated" for the delay in the abolition of the slave trade, which, he claimed, would have been impossible at the time in any case.[59]

In March 2021, the council approved the installation of a permanent plaque "dedicated to the memory of the more than half a million Africans whose enslavement was a consequence of Henry Dundas's actions". The plaque also states Dundas "defended and expanded the British empire, imposing colonial rule on indigenous peoples" and "curbed democratic dissent in Scotland".[3][e] The plaque was installed in October 2021, coinciding with the council's launch of a public survey into Edinburgh's colonial legacy and with the creation of the Edinburgh Slavery and Colonial Legacy Review Group, chaired by Palmer.[60]

In response to the approval of the plaque, two of Dundas' descendants – Jennifer Dundas and Bobby Dundas, the current Viscount Melville – criticised the wording of the plaque. They argued their ancestor was one of the first MPs to support abolition and pointed to his role in the legal defence of Joseph Knight in the Knight v. Wedderburn: the case which led to the effective abolition of slavery in almost all cases in Scotland. Palmer responded by recognising Dundas' role in Knight's case while refuting the claim that Dundas was an abolitionist.[61]

In March 2023 the City of Edinburgh Council planning committee voted to remove the contentious plaque [5] but the council later explained that as the owners they would not do this.[6] and that the vote was a technicality about planning permission.

Description[edit]

Setting[edit]

The monument stands in the centre of St Andrew Square at the eastern end of Edinburgh's New Town. The square was an integral part of James Craig's original scheme and was one of the first parts of the New Town to be developed. The feuing of the square began in 1767 and the square was entirely built by 1781.[62] Initially, the square's gardens were accessible only by inhabitants of the surrounding residences: some of the most desirable in the city. By the time of the monument's construction, however, the square had declined as a residential area and was, as it remains, largely occupied by commercial properties.[63][64] In 2008, the square, as part of its full opening to the public, was redeveloped by the design firm Gillespies. Gillespies' plan created a south west to north east axis across the square, which includes a central oval-shaped open space surrounding the monument.[65]

Craig's original plan of the New Town had proposed equestrian statues at the centres of Charlotte Square and St Andrew Square. The latter would have occupied the site of the Melville Monument.[66] Craig also intended the western and eastern views along George Street would terminate at a church on Charlotte Square and one on St Andrew Square respectively. Although the former was achieved with Robert Reid's St George's Church on Charlotte Square, Sir Lawrence Dundas' purchase of the a plot on the eastern side of St Andrew Square for his own house meant the eastern end lacked such a vista.[67] The construction of the Melville Monument provided that visual terminus to the east end of George Street.[68]

Historic Environment Scotland describes the monument as "among the most prominent landmarks in Edinburgh".[2][69] A.J. Youngson describes the monument as "inescapable" when approaching George Street.[70] The monument occupies a prominent position at the eastern end of the ridge on which the New Town is constructed. Relevant to its origin as a tribute from sailors of the Royal Navy, its position made it visible from ships in the Firth of Forth and to sailors as they travelled from the port at Leith to Edinburgh via Leith Walk.[71]

C.G. Desmarest argues the Melville Monument is a picturesque reaction to the formality of Craig's plan, which it enhances without disrupting it.[72] As the Melville Monument rose, some proposed a similar column, based on that of Antoninus Pius and dedicated to Pitt the Younger for Charlotte Square. If this had been constructed, Desmarest claims, it would have enhanced the formal symmetry of the New Town.[47][f]

Column and pedestal[edit]

The overall design of the column is modelled on the early second-century Trajan's Column in Rome, albeit with a shaft decorated with regular vertical fluting rather than with the relief sculptures of its ancient model. The shaft is also punctuated by vertical slits to illuminate the interior.[20][32]

The shaft is topped by a Doric capital decorated with egg-and-dart moulding: this supports a square pedestal, above which a two-stage drum supports the statue.[2] Within the drum is a door, which provides access to the pedestal from a spiral staircase which ascends the interior of the shaft. The square pedestal at the base of the monument more closely imitates that of its Roman model, especially in the corner eagles with oak leaf swags stretching between them. Access to the internal staircase is via the door in the west face of the pedestal.[20] At its base, the pedestal is approximately 5.5 m (18 ft) at each face and 6.3 m (21 ft) tall.

The column itself is about 35.5 m (117 ft) in height with a diameter at the base of around 3.7 m (12 ft) at the base, tapering to 3.2 m (10.5 ft) at the top. Combined with the pedestal and statue, this gives the monument an overall height of about 45 m (150 ft). The pedestal and column are constructed from Cullalo sandstone.[34][51]

Statue[edit]

The statue, designed by Francis Leggatt Chantrey and carved by Robert Forrest, is constructed from Nethanfoot and Threepwood sandstone and stands at approximately 4.2 m (14 ft) tall.[51] The statue weighs about 18 tons and consists of 15 blocks secured by gunmetal bolts.[1]

The statue depicts its subject clad in the robes of a peer and facing west along George Street with his left hand on his chest and his right foot slightly overstepping the pedestal.[20] This pose is similar to that adopted by Chantrey's 1818 depiction of Dundas, housed in Parliament Hall.[74] Due to the monument's great height, the statue's features are exaggerated, especially the trim of the robes, the hair, and eyebrows. Overall, the statue conforms with contemporary descriptions of its subject as tall and muscular with striking features.[20][69]

Cultural references[edit]

In the children's television series Hububb, which aired on CBBC from 1997 to 2001, the main character, played by mime artist Les Bubb, lives in the Melville Monument.[75]

The immediate response to the controversy around the monument in 2020, inspired a number of works. Jack Docherty's short story "Statuesque", centring on the monument, was broadcast by BBC Radio 4 on 28 June 2020 as part of the station's Short Works series of stories inspired by current events.[76] The monument was the subject of Sunken Statues, a speculative design project by Tom Fairley, which imagines the full length of the monument sunk in a hole in the square. The project won the grand prize at the 2021 John Byrne Awards.[77][78]

The monument was also subject of a BBC Scotland television documentary Scotland, Slavery, and Statues, broadcast on 20 October 2020. Sir Tom Devine criticised the programme as "a kind of Punch and Judy show" and "a miserable failure".[79] The programme's producer, Parisa Urquhart, defended her work, pointing to positive comments from the Wilberforce Diaries Project and from Professor James Smith, Chair of Africa and Development Studies at the University of Edinburgh.[80]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

Explanatory notes[edit]

- ^ The precise circumstances of the commissioning of the monument are obscured by the loss, some time before March 1834, of the committee's minutes from 1817 to 1830.[20]

- ^ This same spot would be occupied by a statue of Dundas' son, Robert, from 1857.[24]

- ^ The plaque is inscribed: THE MELVILLE / MONUMENT / ERECTED IN 1823 IN MEMORY / OF HENRY DUNDAS (1742–1811) / FIRST VISCOUNT MELVILLE AND / A DOMINANT FIGURE IN POLITICS / FOR OVER FOUR DECADES. / BESIDES BEING TREASURERE TO THE NAVY HE / WAS LORD ADVOCATE & KEEPER OF THE / SCOTTISH SIGNET. THE SUBSCRIPTION / FOR THE MONUMENT WAS RAISED BY / MEMBERS OF THE ROYAL NAVY. / IT WAS DESIGNED BY WILLIAM BURN, / AND THE STATUE IS BY CHANTREY.[51]

- ^ Fry made the same argument in his 1992 biography of Dundas, The Dundas Despotism.[54]

- ^ The full text of the approved plaque reads: "At the top of this neoclassical column stands a statue of Henry Dundas, 1st Viscount Melville (1742–1811). He was the Scottish Lord Advocate, an MP for Edinburgh and Midlothian, and the First Lord of the Admiralty. Dundas was a contentious figure, provoking controversies that resonate to this day. While Home Secretary in 1792, and first Secretary of State for War in 1796 he was instrumental in deferring the abolition of the Atlantic slave trade. Slave trading by British ships was not abolished until 1807. As a result of this delay, more than half a million enslaved Africans crossed the Atlantic. Dundas also curbed democratic dissent in Scotland, and both defended and expanded the British empire, imposing colonial rule on indigenous peoples. He was impeached in the United Kingdom for misappropriation of public money, and, although acquitted, he never held public office again. Despite this, the monument before you was funded by voluntary contributions from British naval officers, petty officers, seamen, and marines and was erected in 1821, with the statue placed on top in 1827. In 2020 this plaque was dedicated to the memory of the more than half-a-million Africans whose enslavement was a consequence of Henry Dundas's actions."[3]

- ^ The site proposed for this memorial has been occupied since 1876 by an equestrian memorial to Prince Albert.[73]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Paxton and Shipway 2007, p. 152.

- ^ a b c d e Historic Environment Scotland. "St Andrew Square, Melville Monument with boundary walls and railings (LB27816)". Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ^ a b c Anderson, Joseph (17 March 2021). "Edinburgh Council approve slavery plaque at Henry Dundas Melville Monument". Edinburgh Live. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ^ "Edinburgh Slavery and Colonialism Legacy Review Report and Recommendations" (PDF). 30 August 2022. Retrieved 8 March 2023.

- ^ a b "22/04496/LBC | Removal of plaque. | Melville Statue St Andrew Square Edinburgh" (PDF). 2 March 2023. Retrieved 8 March 2023.

- ^ a b Lloyd, Karen. "Melville Monument Plaque – a clarification". The City of Edinburgh Council. Retrieved 8 March 2023.

- ^ Fry in Matthew and Harrison 2004, xvii p. 274.

- ^ Fry in Matthew and Harrison 2004, xvii p. 275.

- ^ Fry in Matthew and Harrison 2004, xvii p. 276.

- ^ Fry in Matthew and Harrison 2004, xvii p. 275-276.

- ^ McCarthy, Angela (May 2022). "Bad History: The Controversy over Henry Dundas and the Historiography of the Abolition of the Slave Trade". Scottish Affairs. 31 (2): 133–153

- ^ Fry in Matthew and Harrison 2004, xvii p. 279-280.

- ^ Matheson 1933, p. 407.

- ^ McKenzie et al. 2018, i p. 346.

- ^ a b Desmarest 2018, p. 111.

- ^ McKenzie et al. 2018 ii pp. 413–414.

- ^ a b Gray 1927, p. 208.

- ^ Gray 1927, p. 207.

- ^ Desmarest 2018, p. 112.

- ^ a b c d e f Mckenzie et al. 2018 ii p. 413.

- ^ a b c McKenzie et al. 2018 ii p. 414.

- ^ Desmarest 2018, p. 114.

- ^ Youngson 2001, pp. 163–164.

- ^ a b Mckenzie et al. 2018, ii p. 420.

- ^ Gray 1927, pp. 208–209.

- ^ Desmarest 2018, p. 115.

- ^ McKenzie et al. 2018 ii pp. 414–415.

- ^ a b Gray 1927, p. 209.

- ^ Grant 1880, ii p. 171.

- ^ Mckenzie et al. 2018, ii p. 415.

- ^ McKenzie et al. 2018, ii pp. 415–416.

- ^ a b Gifford, McWilliam, Walker 1984, p. 322.

- ^ Gray 1927, p. 210.

- ^ a b c Lindsay 1948, p. 41.

- ^ Byrom 2005, p. 37

- ^ Mckenzie et al. 2018, ii p. 416.

- ^ Byrom 2005, pp. 38–39.

- ^ McKenzie et al. 2018, ii p. 417.

- ^ a b Byrom 2005, p. 39.

- ^ McKenzie et al. 2018, ii pp. 417–418.

- ^ Gray 1927, pp. 211–213.

- ^ McKenzie et al. 2018, ii pp. 418–419.

- ^ Fry 1992, p. 314.

- ^ Cockburn 1856, p. 79.

- ^ a b Desmarest 2018, p. 125.

- ^ Trevelyan 1876, i p. 109.

- ^ a b Desmarest 2018, p. 105.

- ^ Desmarest 2018, p. 107.

- ^ McKenzie et al. 2018, ii p. 419.

- ^ Byrom 2005, p. 46.

- ^ a b c Mckenzie et al. 2018 ii p. 411.

- ^ Desmarest 2018, pp. 125–126.

- ^ "Twelve Monuments: A Monumental Endeavour". ewh.org.uk. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ^ Fry 1992, pp. 199–201.

- ^ Mackenzie, Steven (27 June 2020). "Scotland's first Black academic on why we shouldn't remove offending statues". Big Issue. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ^ a b Hay, Katharine (6 June 2020). "Edinburgh professor renews call to reword history on a statue memorialising man who prolonged the slave trade". Edinburgh Evening News. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- ^ Hislop, John (9 June 2020). "Black Lives Matter graffiti on base of Melville Monument". Edinburgh Evening News. Retrieved 4 July 2021.

- ^ Hoffman, Noa (13 July 2020). "New signs appear around Edinburgh's Melville Monument outlining Henry Dundas' involvement in the slave trade". Edinburgh Evening News. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ^ McKenna, Kevin (25 October 2020). "Scots historian Sir Tom Devine criticises rush to 'clarify' slave trader Henry Dundas' actions". The Herald. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ^ Campbell, Jolene (26 October 2021). "'The voice of the people has been heard' – human rights campaigner Sir Geoff Palmer hails new Edinburgh slavery plaque". Edinburgh Evening News. Retrieved 23 April 2022.

- ^ Anderson, Joseph (20 March 2021). "Dundas plaque row: Descendants of Dundas 'surprised and disappointed' at 'false' plaque wording". Edinburgh Evening News. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ^ Youngson 1966, pp. 81–91.

- ^ Youngson 1966, pp. 228–229, 232–233.

- ^ Grant 1880, ii p. 166.

- ^ "St Andrew Square". gillespies.co.uk. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ^ McKenzie et al. 2018, ii p. xii.

- ^ McWilliam 1975, p. 80.

- ^ Desmarest 2018, p. 121.

- ^ a b "Melville Monument". ewh.org.uk. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- ^ Youngson 2001, p. 163.

- ^ Desmarest 2018, p. 122.

- ^ Desmarest 2018, p. 126.

- ^ Gifford, McWilliam, Walker 1984, pp. 293–294.

- ^ Desmarest 2018, p. 123.

- ^ "Top Kids' TV in Edinburgh". filmedinburgh.org. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ^ "BBC Radio 4 – Short Works, Statuesque". bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- ^ "The Uncrowned King of Scotland: the man behind the Melville Monument". artuk.org. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

- ^ "Is our past set in stone?: Tom Fairley". johnbyrneaward.org.uk. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

- ^ Devine, Tom (25 October 2020). "Sir Tom Devine: Scapegoating of Henry Dundas on the issue of Scottish slavery is wrong - and BBC documentary was a miserable failure". The Herald. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

- ^ Urquhart, Parisa (9 November 2020). "BBC documentary maker defends her work after top historian's scathing condemnation". Big Issue. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

Bibliography[edit]

- Anstey, Roger (1975). The Atlantic Slave Trade and British Abolition. MacMillan SBN 333-14846-0

- Byrom, Connie (2005). The Edinburgh New Town Gardens. Birlinn ISBN 1-84158-402-9

- Cockburn, Henry (1856). Memorial of his Time. (1979 ed.) The University of Chicago Press

- Davis, David Brion (1975). The Problem of Slavery in the Age of Revolution: 1770–1823. (1999 ed.) Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195126716

- Desmarest, Clarisse Godard (2018). "The Melville Monument and the Shaping of the Scottish Metropolis". Architectural History. 61: 105–130. doi:10.1017/arh.2018.5. S2CID 231734564. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- Fry, Michael (1992). The Dundas Despotism. John Donald ISBN 0-85976-588-1

- Gifford, John; McWilliam, Colin; Walker, David (1984). The Buildings of Scotland: Edinburgh. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-071068-X

- Grant, James (1880). Old and New Edinburgh. II. Cassell's

- Gray, William Forbes (1927). "The Melville Monument". Book of the Old Edinburgh Club. XV: 207–213.

- Lindsay, Ian G. (1948). Georgian Edinburgh. Oliver and Boyd.

- James, C.L.R. (1938). The Black Jacobins: Toussaint L'Ouverture and the San Domingo Revolution. Penguin.

- McKenzie, Ray; King, Dianne; Smith, Tracy (2018). Public Sculpture of Britain Volume 21: Public Sculpture of Edinburgh. Liverpool University Press. ISBN 978-1-78694-155-8

- McWilliam, Colin (1975). Scottish Townscape. Collins. ISBN 9780002167437

- Matthew, H.C.G. & Harrison, Brian (eds.) (2004) Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. XVII. Oxford University Press ISBN 0-19-861367-9

- Fry, Michael. "Dundas, Henry, first Viscount Melville (1742–1811)".

- Matheson, Cyril (1933). The Life of Henry Dundas, 1st Viscount Melville. Constable & Co

- Paxton, Richard & Shipway, Jim (2007). Civil Engineering Heritage: Scotland – Lowlands and Borders. Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historic Monuments of Scotland. ISBN 978-0-7277-3487-7

- Trevelyan, George Otto (ed.) (1876). Life and Letters of Lord Macaulay.

- Youngson, Alexander J.

- (1966). The Making of Classical Edinburgh. Edinburgh University Press.

- (2001). The Companion Guide to Edinburgh and the Borders. Polygon. ISBN 0-7486-6307-X