Wikipedia:Wikipedia Signpost/2022-10-31/Disinformation report

From Russia with WikiLove

- A recent academic report, widely cited in the mainstream press (see this issue's "In the media"), has suggested that Russian agents have edited Wikipedia through the use of sockpuppets. Readers of The Signpost should not be surprised by this report. I have documented similar allegations about paid editing by Russians and others several times, for example in The oligarchs' socks and "I have been asked by Jeffrey Epstein …".

- I have edited articles I thought were written by foreign agents and interacted with some of the Wikipedia editors mentioned below. The opinions expressed below are mine alone and do not necessarily reflect those of The Signpost or its staff, or of any other Wikipedia editors. – S

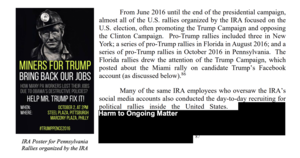

Do Russian agents, paid directly by the government or by people close to President Vladimir Putin, edit Wikipedia? There are many reasons to think that they would if they thought it would be successful. Russia interfered with the 2016 U.S. Presidential election and other Western elections by means of the internet, according to the Mueller report. Much of their effort used social media such as Facebook, Twitter, or video sites. Russians are certainly aware of Wikipedia's reach and credibility and the Russian government has attempted several times to establish Russian online encyclopedias as alternatives to Wikipedia. Its agents have the motivation and opportunity to spread their disinformation, but do they have the ability to avoid Wikipedia’s defenses?

A new tool

A report from the Centre for Analysis of Social Media division of the Institute for Strategic Dialogue titled Information Warfare and Wikipedia examines this question, and proposes a potentially useful method of assessing whether Russian agents have edited Wikipedia.

The lead author of the report, Carl Miller, may be familiar to Signpost readers through his reporting on the BBC on disputes between Taiwanese and Mainland Chinese editors (program) in 2019 and disputes between Hong Kong and Mainland Chinese editors in 2021. I’ve also interviewed him in The Signpost.

Suggestions of coordinated editing from 86 accounts

The report starts with a review of the current state of disinformation operations on the internet. The review may be especially useful to Wikipedians who haven't followed recent changes in disinformation techniques. It then gives the basics of Wikipedia operations, and factors that could make the site attractive to spreaders of disinformation. This section should be quite familiar to many Wikipedians, but is followed by a more challenging section on how Wikipedia fights disinformation. If you need to learn about sockpuppet investigations and checkusers, this is a good short introduction.

The most interesting section is a case study of the article on the Russo-Ukrainian war, which was started in March 2014 (soon after Russian soldiers seized two Crimean airports and deposed the prime minister of Crimea, but before Russia illegally annexed the region). The goal of the case study was to explore potential Russian disinformation inserted in the article over the next eight years, by using methods that could be automated at scale and used by other researchers in other studies of disinformation on Wikipedia.

The authors identified article editors who were later banned by administrators or checkusers, generally via sockpuppet investigations. The beauty of this method is that outside researchers do not need to judge whether Wikipedia rules have been broken – an often difficult and contentious task. They only need to know that the editors have been banned, a fact reported in the article's edit history, with data gathering fairly easily automated.

They identified 89 accounts that were banned, mostly for sockpuppeting. After eliminating three bots, they were left with 86 "suspicious" editors. These editors' editing history was examined, including edits made on other articles where two or more of them crossed paths, describing a network of editors and articles edited by them.

Some of the media articles about this report seem to take the existence of this network as "proof" of Russian government editing. In reality, it is clearly not that easy to draw such a conclusion. What they found was people inserting pro-Russian bias; whether this was commissioned by the Kremlin remains unclear. The report’s authors find the existence of the network only as suggestive of coordinated editing, and conclude that there is evidence of "a particular strategy used by bad actors of splitting their edit histories between a number of accounts to evade detection". They stress a possible strategy of entryism, or infiltration of Wikipedia by Russian agents. While there are clearly limitations on using this methodology, it looks like a step forward in the search for a way to examine particularly contentious topics where hundreds of editors may be making thousands of edits across dozens of articles.

Another approach

So where do we stand now? Do Russian agents edit Wikipedia articles? The academic approach to this question has so far given an answer of essentially we have a method that has identified 86 editors, with many of them looking suspicious. Fortunately we have the complementary methods of journalism which generally look at the cases of individuals or small groups. I believe that most Wikipedians who look at the following cases will conclude that yes, there appear to be some Russian agents editing Wikipedia. But we must note that no analysis of Wikipedia edits can prove to the standards of a criminal court the identity of a Wikipedia editor.

An unregistered foreign agent of Russia

Maria Butina was a Russian student at American University, who was also working with the high ranking Russian politician – Deputy Governor of Russia’s Central Bank (and suspected member of the Russian Mafia) Aleksandr Torshin. Butina and Torshin attended meetings of the National Rifle Association together, attempted to connect with associates of Donald Trump, and are suspected of attempting to donate money to the Trump campaign via the NRA. In 2018, she was convicted of acting as an unregistered foreign agent of Russia while in the U.S. and served 18 months in federal prison before being deported to Russia. She received a hero's welcome on her return, became a television presenter, and was soon elected to the Russian State Duma.

In 2018, the Daily Beast published an article titled "Who Whitewashed the Wiki of Alleged Russian Spy Maria Butina?" strongly suggesting that it was a specifically named editor, who was Maria Butina. Furthermore, there was an anonymous unregistered IP editor from the same university as Butina.

That article, and five other articles from reliable sources reporting similar facts, are listed at Talk:Maria Butina. The editors of the talk page noticed the first news article, generally accepted it as factual, and cleaned the article of the offending edits. The editor suspected to have been Butina denied the allegations on their user talk page.

Fertilizer from the oligarchs' sockfarms

In the March Signpost article "The oligarchs' socks", I reported on eight well-known Russian oligarchs: Alisher Usmanov, Roman Abramovich and his son Arkadiy Abramovich, Oleg Deripaska, Mikhail Fridman, German Khan, Alexander Nesis, and Andrei Skoch.

Usmanov hired the PR firm RLM Finsbury, who then edited his Wikipedia article. Finsbury admitted this in 2012. The articles on A. Abramovich and Nesis were almost certainly edited by the disgraced (and now defunct) political PR firm Bell Pottinger.

Fifty now-blocked sockpuppets edited the article on Roman Abramovich, thirty edited the Deripaska article, but less than ten edited the articles on Fridman, Khan, and Skoch. There is a overlapping pattern of edits by the same sockfarms (large groups of sockpuppets named together in sockpuppet investigations).

Banned user Russavia edited two of the oligarch articles. He was a very active administrator on Wikimedia Commons, who specialized in promoting the Russian aviation industry, and in disrupting the English-language Wikipedia. After finally being banned on the English Wikipedia, he created dozens of sockpuppets. Russavia, by almost all accounts, is not a citizen or resident of Russia, but his edits raise some concern and show some patterns.

In 2010, he boasted, on his userpage at Commons, that he had obtained permission from the official Kremlin.ru site for all photos there to be uploaded to Commons under Creative Commons licenses. He also made 148 edits at Russo-Georgian War, and 321 edits on the ridiculously detailed International recognition of Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Both of these articles were, at one time, strongly biased in favor of Russia.

Conclusion

The Russian government is now engaged in a brutal war in Ukraine, or as they call it, a "special military operation". They are widely reported as supporting this war and other controversial activities with a disinformation war, including inserting disinformation on social media sites. Wikipedia is apparently not immune from these activities. Russian agents have the motivation and opportunity, and allegedly the ability, to insert their disinformation here. We should continue to investigate and report this activity, using the tools of journalism and the tools now being developed by academic researchers.

- See also In the media and Recent research in this month's Signpost.

- ^ Barron, John (1974), KGB: the secret work of Soviet secret agents, Reader's Digest Press, ISBN 0883490099

- ^ "Analysis: The strongest evidence yet that UAE is trying to meddle in U.S. politics. The Cybersecurity 202". Washington Post. November 14, 2022. Retrieved November 15, 2022.

{{cite news}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help)

Discuss this story

Excellent article. Thanks as always User:Smallbones. Doc James (talk · contribs · email) 13:06, 1 November 2022 (UTC) Good article. I've noticed that articles relating to Dubai are often full of praise for it, sometimes with references that are barely relevant to what is being said. I suspect that there are agents of many other countries involved, and some don't get as much attention as Russia's. Epa101 (talk) 00:00, 6 November 2022 (UTC)[reply]

John Barron told us all what the Chekists were up to in 1974.[1] Anyone who thinks they ever stopped is ignorant (some willfully and most merely negligently). Of course once Wikipedia was invented, their playbook version builds were updated accordingly, as that would be self-evidently logical. It is all part of the history of their sewage disposal system, as the premier record puts it. As one of their own has said, there isn't even any such thing as a former KGB man. They think it's hilarious, and quite useful to them, how little institutional memory most of the rest of us have. Meanwhile, The Washington Post told us just this week what sorts of things the UAE has been up to.[2] But people have Pokemon to farm on Twitch, or some bullshit like that, so you can see the bind they're in, regarding maintaining vigilance or at least awareness. I'm not even one to go on and on about it all, trying to get anyone else to pay attention or read a little nonfiction or a little real news once in a while, but I just feel weird regarding how little 99% of people bother to have even a crumb of awareness (like "what's a Chekist?"), considering the threats and risks involved. Again, no time though, what with amusing themselves to death, I guess? Albums dropping on the Insta or some bullshit like that. They know way more about cartoon/movie mafia dons than the much more dangerous real-life mafia dons that actually threaten real lives. Or maybe they just imagine that they "see their souls when they look into their eyes" (what souls?), or fawn over them as fellow stable geniuses or some bullshit like that. Who knows; this ain't my day job. At least a few people are standing watch and telling the rest of us. Karmanatory (talk) 04:31, 16 November 2022 (UTC)[reply]