93rd Academy Awards

| 93rd Academy Awards | |

|---|---|

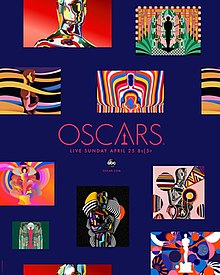

Official poster | |

| Date | April 25, 2021 |

| Site | Union Station Los Angeles, California, U.S.[a] |

| Preshow hosts | |

| Produced by |

|

| Directed by | Glenn Weiss |

| Highlights | |

| Best Picture | Nomadland |

| Most awards | Nomadland (3) |

| Most nominations | Mank (10) |

| TV in the United States | |

| Network | ABC |

| Duration | 3 hours, 19 minutes[5] |

| Ratings |

|

The 93rd Academy Awards ceremony, presented by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS), honored films released from January 1, 2020, to February 28, 2021, at Union Station in Los Angeles.[a] The ceremony was held on April 25, 2021, rather than its usual late-February date due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[8] During the ceremony, the AMPAS presented Academy Awards (commonly referred to as Oscars) in 23 categories. The ceremony, televised in the United States by ABC, was produced by Jesse Collins, Stacey Sher, and Steven Soderbergh, and was directed by Glenn Weiss.[9][10] For the third consecutive year, the ceremony had no official host.[11] In related events, the Academy Scientific and Technical Awards were presented by host Nia DaCosta on February 13, 2021, in a virtual ceremony.[12]

Nomadland won three awards at the main ceremony, including Best Picture.[13] Other winners included The Father, Judas and the Black Messiah, Ma Rainey's Black Bottom, Mank, Soul and Sound of Metal with two awards each, and Another Round, Colette, If Anything Happens I Love You, Minari, My Octopus Teacher, Promising Young Woman, Tenet, and Two Distant Strangers with one. The telecast received mostly negative reviews, and it garnered 10.4 million viewers, making it the least-watched Oscar broadcast since viewership records began for the 46th ceremony in 1974.[6][14][15]

Winners and nominees[edit]

The nominees for the 93rd Academy Awards were announced on March 15, 2021, by actress Priyanka Chopra and singer Nick Jonas during a live global stream originating from London.[16] Mank led all nominees with ten nominations. The winners were announced during the awards ceremony on April 25.[17] Chinese filmmaker Chloé Zhao became the first woman of color to win Best Director and the second woman overall after Kathryn Bigelow, who won at the 2010 ceremony for directing The Hurt Locker.[18]

At age 83, Best Actor winner Anthony Hopkins was the oldest performer to ever win a competitive acting Oscar.[19] Best Actress winner Frances McDormand became the seventh person to win a third acting Oscar, the third to win three leading performance Oscars, and the second to win Best Actress three times.[20] As a producer of Nomadland, she also was the first person in history to win Oscars for both acting and producing for the same film.[21]

Best Supporting Actress winner Yuh-jung Youn became the first Korean performer and second Asian woman to win an acting Oscar after Miyoshi Umeki, who won the same category for her role in 1957's Sayonara.[22] With his nominations in Best Supporting Actor and Best Original Song for One Night in Miami..., Leslie Odom Jr. was the fourth consecutive person to earn acting and songwriting nominations for the same film.[b]

Awards[edit]

Winners are listed first, highlighted in boldface, and indicated with a double dagger (‡).[24]

Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award[edit]

There were two recipients of the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award:[25]

- Tyler Perry – for his active engagement with philanthropy and charitable endeavors in recent years, including efforts to address homelessness and economic difficulties faced by members of the African-American community.

- Motion Picture & Television Fund – for the emotional and financial relief services it offers to members of the entertainment industry.

Film awards and nominations[edit]

| Nominations | Film |

|---|---|

| 10 | Mank |

| 6 | The Father |

| Judas and the Black Messiah | |

| Minari | |

| Nomadland | |

| Sound of Metal | |

| The Trial of the Chicago 7 | |

| 5 | Ma Rainey's Black Bottom |

| Promising Young Woman | |

| 4 | News of the World |

| 3 | One Night in Miami... |

| Soul | |

| 2 | Another Round |

| Borat Subsequent Moviefilm | |

| Collective | |

| Emma | |

| Hillbilly Elegy | |

| Mulan | |

| Pinocchio | |

| Tenet |

| Awards | Film |

|---|---|

| 3 | Nomadland |

| 2 | The Father |

| Judas and the Black Messiah | |

| Ma Rainey's Black Bottom | |

| Mank | |

| Soul | |

| Sound of Metal |

Presenters[edit]

The following individuals, listed in order of appearance, presented awards or performed musical numbers.[26][27]

Performers[edit]

| Name | Role | Work |

|---|---|---|

| Molly Sandén | Performer | "Husavik" from Eurovision Song Contest: The Story of Fire Saga |

| Laura Pausini and Diane Warren | Performers | "Io sì (Seen)" from The Life Ahead |

| Celeste | Performer | "Hear My Voice" from The Trial of the Chicago 7 |

| Leslie Odom Jr. | Performer | "Speak Now" from One Night in Miami... |

| H.E.R. | Performer | "Fight for You" from Judas and the Black Messiah |

Ceremony[edit]

In April 2017, the Academy scheduled the 93rd ceremony for February 28, 2021.[28] However, due to the impacts stemming from the COVID-19 pandemic on both cinema and television, the AMPAS Board of Governors later decided to move the date for the 2021 gala by two months to April 25.[29] The annual Academy Governors Awards and corresponding nominees luncheon were canceled due to COVID-19 safety concerns.[30] This marked the first time since the 60th ceremony held in 1988 that the awards were held in April.[31] It also was the first time since the 53rd ceremony in 1981 that the ceremony was postponed from its original date.[32]

In December 2020, the Academy hired television producer Jesse Collins, film producer Stacey Sher, and Oscar-winning director Steven Soderbergh to oversee production of the telecast. "The upcoming Oscars is the perfect occasion for innovation and for re-envisioning the possibilities for the awards show. This is a dream team who will respond directly to these times. The Academy is excited to work with them to deliver an event that reflects the worldwide love of movies and how they connect us and entertain us when we need them the most," remarked Academy president David Rubin and CEO Dawn Hudson.[33]

The tagline for the ceremony, "Bring Your Movie Love", was intended to reflect "our global appreciation for the power of film to foster connection, to educate, and to inspire us to tell our own stories."[34] In tandem with the theme, the Academy hired seven artists to create custom posters for the event inspired by the question, "What do movies mean to you?"[35] Another aspect of the telecast's production was to produce the ceremony as if it were a film, including promoting the presenters as a "cast",[36][37] being filmed at the traditional cinematic frame rate of 24 frames per-second as opposed to 30, and using a cinematic aspect ratio rather than the standard 16:9 aspect ratio used by most television programming.[38]

As a result of concerns stemming from the pandemic, AMPAS announced that the main ceremony would be held for the first time at Union Station in Downtown Los Angeles with portions of the festivities taking place at Dolby Theatre in Hollywood.[39] To satisfy health and safety protocols, the Academy limited the number of people attending the gala to primarily nominees and presenters.[37][40] Attendees were asked to submit travel plans to Oscar organizers prior to arriving in Los Angeles and undergo multiple COVID-19 tests and isolation ten days prior to the event.[41] Guests were also asked to wear face masks whenever the broadcast paused for commercial breaks.[42] In consideration of overseas nominees unable to attend the ceremony, producers set up satellite "hubs" such as at BFI Southbank in London where they could participate in the gala.[43][44] Additionally, the five Best Original Song nominees were performed in previously recorded segments that were shown during the red carpet pre-show. Four of the songs were performed atop the Dolby Family Terrace of the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures; "Husavik" from Eurovision Song Contest: The Story of Fire Saga was performed on location in the song's namesake town in Iceland.[3]

The Roots musician and The Tonight Show bandleader Questlove served as musical director for the ceremony.[45] He, along with Oscars red carpet pre-show host Ariana DeBose and actor Lin-Manuel Miranda, presented trailers for the upcoming films Summer of Soul (...Or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised), West Side Story, and In the Heights, respectively, during the ceremony.[46][47] Architect David Rockwell served as production designer for the show.[48] In a press conference between the production team and reporters, Rockwell stated that the main lobby inside Union Station would be repurposed as the main setting for the awards presentation while adjacent outdoor areas would serve as patios for attendees to congregate before and after the ceremony.[49] He also cited the Millennium Biltmore Hotel and The Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel, the latter of which was the venue of the inaugural Oscars ceremony, as inspirations for the design and staging of the festivities.[50] Actors Colman Domingo and Andrew Rannells hosted Oscars: After Dark, a program airing immediately after the ceremony interviewing winners and nominees.[51]

The ceremony offered accommodations for those who are deaf or visually impaired; it was the first Academy Awards to be broadcast with audio description for the visually impaired (carried via second audio program on the ABC telecast), which (along with its closed captioning) was sponsored by Google. A sign language interpreter was available in the media room. Contrarily, deaf actress Marlee Matlin served as one of the award presenters, with her long-time partner Jack Jason interpreting her American Sign Language to spoken English.[52][53][54]

Eligibility and other rule changes[edit]

Due to the ceremony date change, the Academy changed the eligibility deadline for feature films from December 31, 2020, to February 28, 2021. AMPAS president Rubin and CEO Hudson explained the decision to extend the eligibility period saying, "For over a century, movies have played an important role in comforting, inspiring, and entertaining us during the darkest of times. They certainly have this year. Our hope, in extending the eligibility period and our Awards date, is to provide the flexibility filmmakers need to finish and release their films without being penalized for something beyond anyone's control."[55]

The Academy also revised its release and distribution requirements by allowing for films that were released via video on demand or streaming to be eligible for the awards on the condition that said films were originally scheduled to have a theatrical release and were subsequently uploaded to AMPAS's online screening service within 60 days of their public release. AMPAS also amended its theatrical exhibition qualifying rules to allow films debuting in theaters located in New York City, Chicago, the San Francisco Bay Area, Atlanta, and Miami to qualify for the awards in addition to venues in Los Angeles.[56] Moreover, a week of nightly screenings at a drive-in theater within the aforementioned cities also rendered films eligible for consideration.[57]

Furthermore, the Academy made changes to specific award categories. The Best Sound Mixing and Best Sound Editing categories were combined into a single Best Sound category due to concerns from the Sound branch that the two categories had too much overlap in scope.[58] The rules for Best Original Score were changed to require that a film's score include a minimum of 60% original music, with franchise films and sequels being required to have a minimum of 80% new music.[59] Finally, preliminary voting for Best International Feature Film was also opened to all voting members of the Academy for the first time.[60]

Best Actor announcement ending[edit]

In a break with tradition, the lead acting categories were presented last after the awarding of Best Picture, with Best Actor coming last.[61] This led many viewers to believe that the ceremony's producers were anticipating Chadwick Boseman posthumously winning Best Actor, which could have been accompanied by a tribute to the actor; Boseman had been considered a strong frontrunner for the award.[62][63] When presenter Joaquin Phoenix announced that Anthony Hopkins was the winner of the category, Phoenix said that the Academy accepted the award on behalf of the latter, who was not present, and the ceremony came to an abrupt end.[63] It was later reported that Hopkins, who did not want to travel from his home in Wales, offered to appear via Zoom, but the producers declined his request.[63]

The day after the ceremony, he released an acceptance speech on Instagram, in which he thanked the Academy, said that he "really did not expect" to win, and paid tribute to Boseman.[62] The selection of Hopkins over Boseman was controversial, with some feeling like it was a setup,[64][65] though Boseman's brother reported the family did not have any hard feelings toward the Academy.[66]

In a subsequent interview with the Los Angeles Times, Soderbergh said that switching the traditional order of awards was planned before the nominations were announced, claiming "actors' speeches tend to be more dramatic than producers' speeches". He said that the possibility of Boseman's widow accepting the award "would have been such a shattering moment" and "there would be nowhere to go after that". Soderbergh also defended the decision to not allow acceptance speeches via Zoom.[67]

Critical reviews[edit]

Many media outlets received the broadcast negatively.[14][15] On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, 24% of 34 critics' reviews are positive. The website's consensus reads: "The 93rd Oscars definitely delivered something different, but after a strong opening moment with Regina King, the changes to this year's ceremony cemented the importance of certain structural traditions -- and how damaging hedging your bets on the Academy's votes can be."[68] Television critic Mike Hale of The New York Times wrote, "Sunday's broadcast on ABC was more like a cross between the Golden Globes and the closing-night banquet of a long, exhausting convention." He also commented, "The trade-off — whether because of the smaller crowd, the social distancing, or the sound quality in the cavernous space — was what felt like a dead room, both acoustically and emotionally. There were powerful and moving speeches, but they didn't seem to be generating much excitement, and when the people in the room aren't excited, it's hard to get excited at home."[69] Rolling Stone columnist Rob Sheffield noted, "The most flamboyantly unplanned and half-assed Oscar Night in recent history was a grind from beginning to end." He also criticized the production of the "In Memoriam" segment saying that the montage was edited at an inappropriately fast pace.[70] Kelly Lawler of USA Today commented, "While it was certainly challenging to stage the show safely, last month's Grammys proved that it is possible to make something entertaining and engaging amid the pandemic. Unfortunately, the Oscars producers seemingly missed that show. The Oscars were a train wreck at the train station, an excruciatingly long, boring telecast that lacked the verve of so many movies we love."[71]

Others gave a more favorable review of the show. Time columnist Judy Berman wrote that the ceremony "was more entertaining than the average pre-COVID Oscars. It started out especially strong." She also added, "Every part of this year's ceremony felt more intimate and less stuffy than just about any awards show I can remember. For once, the art and community of film seemed to take precedence over the business of film."[72] Associated Press reporter Lindsey Bahr commented, "The 93rd Academy Awards wasn't exactly a movie, but it was a show made for people who love learning about movies. And it stubbornly, defiantly wasn't trying to be anything else."[73] Darren Franlch of Entertainment Weekly gave an average review of the telecast, but singled out the winners and presenters for providing memorable moments throughout the show.[74]

Ratings and reception[edit]

The American telecast on ABC drew in an average of 10.4 million people over its length, which was a 56% decrease from the previous year's ceremony.[75] The show also earned lower Nielsen ratings compared to the previous ceremony with 5.9% of households watching the ceremony.[7] In addition, it garnered a lower rating among viewers between ages 18–49 with a 2.1 rating among viewers in that demographic.[76] It earned the lowest viewership for an Academy Award telecast since figures were compiled beginning with the 46th ceremony in 1974.[77]

In July 2021, the ceremony presentation received eight nominations for the 73rd Primetime Emmy Awards.[78] Two months later, the ceremony won for Outstanding Production Design for a Variety Special (Alana Billingsley, Joe Celli, Jason Howard, and David Rockwell).[79]

Censorship in China and Hong Kong[edit]

The ceremony was subject to various forms of censorship in China and its territories. Due to scrutiny over Nomadland director Chloé Zhao—a Chinese-American citizen who reportedly made comments critical of China in a 2013 interview with Filmmaker magazine—the ceremony telecast was pulled by its local rightsholders in the mainland, and all discussions of the ceremony were censored from Chinese social media and news outlets.[80][81]

In addition, Hong Kong broadcaster TVB announced that the ceremony would not be shown live in the region for the first time since 1969. A TVB spokesperson told AFP that this was a "commercial decision". It was speculated that the decision was in retaliation for the nomination of Do Not Split, a documentary on Hong Kong's pro-democracy protests in 2019, for Best Documentary Short Subject.[82]

"In Memoriam"[edit]

The annual "In Memoriam" segment was presented by Angela Bassett.[83][84] The montage featured the song "As" by singer Stevie Wonder.[85]

- Cicely Tyson – actress

- Ian Holm – actor

- Max von Sydow – actor

- Cloris Leachman – actress

- Yaphet Kotto – actor

- Joel Schumacher – director

- Bertrand Tavernier – director

- Jean-Claude Carrière – writer, director

- Olivia de Havilland – actress

- Irrfan Khan – actor

- Michael Apted – director, producer

- Paula Kelly – actress

- Christopher Plummer – actor

- Allen Daviau – cinematographer

- George Segal – actor

- Wilford Brimley – actor

- Thomas Jefferson Byrd – actor

- Marge Champion – actress, dancer, choreographer

- Ron Cobb – production designer, concept artist

- Shirley Knight – actress

- José Luis Diaz – sound editor

- Kelly Preston – actress

- Rhonda Fleming – actress

- Kelly Asbury – director, writer, animator

- Fred Willard – actor

- Hal Holbrook – actor

- Kurt Luedtke – writer

- Linda Manz – actress

- Michael Chapman – cinematographer, director

- Martin Cohen – producer

- Kim Ki-duk – director, writer

- Helen McCrory – actress

- Ennio Morricone – composer

- Thomas Pollock – executive

- Carl Reiner – actor, writer, director, producer

- Larry McMurtry – writer

- Lynn Shelton – director

- Earl Cameron – actor

- Alan Parker – director, writer

- Mike Fenton – casting director

- Edward S. Feldman – producer

- Lynn Stalmaster – casting director

- Nanci Ryder – publicist

- Sumner Redstone – executive

- Rémy Julienne – stunt performer

- Stuart Cornfeld – producer

- Ronald L. Schwary – producer

- Jonathan Oppenheim – film editor

- Al Kasha – composer

- Charles Gordon – producer

- Brian Dennehy – actor

- Charles Gregory Ross – hairstylist

- Alberto Grimaldi – producer

- Johnny Mandel – composer

- Brenda Banks – animator

- George Gibbs – special effects

- Haim Shtrum – studio musician

- Lennie Niehaus – composer

- Leslie Pope – set decorator

- Joan Micklin Silver – director, writer

- Roberta Hodes – script supervisor, writer

- Ken Muggleston – set decorator

- Diana Rigg – actress

- Leon Gast – documentarian

- Anthony Powell – costume designer

- Chuck Bail – stunt performer

- Bhanu Athaiya – costume designer

- Colleen Callaghan – hairstylist

- Peter Lamont – production designer

- David Giler – writer, producer

- Norman Newberry – art director

- Zhang Zhao – executive, producer

- Conchata Ferrell – actress

- Alan Robert Murray – sound editor

- Andrew Jack – dialect coach

- Jonas Gwangwa – composer

- Marvin Westmore – makeup artist

- Pembroke Herring – film editor

- Lynda Gurasich – hairstylist

- Michel Piccoli – actor

- William Bernstein – executive

- Cis Corman – casting director, producer

- Michael Wolf Snyder – production sound mixer

- Ja'Net DuBois – actress

- Les Fresholtz – re-recording mixer

- Jerry Stiller – actor

- Earl "DMX" Simmons – songwriter, actor, producer

- Giuseppe Rotunno – cinematographer

- Else Blangsted – music editor

- Ronald Harwood – writer

- Masato Hara – producer

- Robert C. Jones – film editor, writer

- Walter Bernstein – writer, producer

- Sean Connery – actor

- Chadwick Boseman – actor

See also[edit]

- List of television shows notable for negative reception

- List of submissions to the 93rd Academy Awards for Best International Feature Film

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b The presentation of the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award to the Motion Picture & Television Fund was held at the Dolby Theatre in Hollywood, California, and the winner of the Best Director was announced from the Dolby Cinema in Seoul, South Korea.[1][2] Furthermore, four of the Best Original Song nominees were performed at the Dolby Family Terrace of the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures, and one was performed on location in Húsavík, Iceland.[3]

- ^ The three previous individuals to have earned this distinction are Mary J. Blige for Mudbound, Lady Gaga for A Star Is Born, and Cynthia Erivo for Harriet.[23]

References[edit]

- ^ Garvey, Marianne (April 25, 2021). "Bryan Cranston applauds 70 vaccinated frontline workers at the Dolby Theatre". CNN. Archived from the original on June 24, 2021. Retrieved May 16, 2021.

- ^ Carras, Christi (April 25, 2021). "'Parasite' director Bong Joon Ho returns to Oscars with interpreter Sharon Choi". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on April 30, 2021. Retrieved May 13, 2021.

- ^ a b Perez, Lexy (April 25, 2021). "Oscars: H.E.R. Wins Best Original Song for "Fight For You", Promises "I'm Always Going to Fight for My People"". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on June 24, 2021. Retrieved June 2, 2021.

- ^ Willman, Chris (April 16, 2021). "Oscars Reveal Original Song Performers and Aftershow Plans". Variety. Archived from the original on May 5, 2021. Retrieved May 2, 2021.

- ^ Barnes, Brooks; Koblin, John (April 26, 2021). "Oscars Ratings Plummet, With Fewer Than 10 Million Tuning In". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 1, 2021. Retrieved May 1, 2021.

- ^ a b Patten, Dominic (April 27, 2021). "Oscar Viewership Rises To 10.4M In Final Numbers; Remains Least Watched & Lowest Rated Academy Awards Ever – Update". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on April 27, 2021. Retrieved April 27, 2021.

- ^ a b "Academy Awards ratings" (PDF). Television Bureau of Advertising. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 8, 2016. Retrieved June 19, 2021.

- ^ "Academy Delays 2021 Oscars Ceremony Because of Coronavirus". Tampa Bay Times. June 15, 2020. Archived from the original on June 17, 2020. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- ^ Truitt, Brian (December 8, 2021). "Director Steven Soderbergh Will Co-produce upcoming Academy Awards Ceremony". USA Today. Archived from the original on December 15, 2020. Retrieved January 28, 2021.

- ^ Hipes, Patrick (March 24, 2021). "Oscars Production Team a Mix Of Veterans And Newcomers Including Questlove, Richard LaGravenese, Dream Hampton". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on March 24, 2021. Retrieved March 25, 2021.

- ^ Freiman, Jordan (April 26, 2021). "Oscars 2021: Full list of winners and nominees". CBS News. Archived from the original on June 1, 2021. Retrieved June 19, 2021.

- ^ Welk, Brian (February 2, 2021). "Oscars Present 17 Awards for Technical and Scientific Achievement". TheWrap. Archived from the original on June 24, 2021. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ^ Lowry, Brian (April 26, 2021). "Academy Awards 2021: 'Nomadland' wins Best Picture At an Oscars That Spreads the Wealth". CNN. Archived from the original on April 27, 2021. Retrieved April 27, 2021.

- ^ a b Lang, Brett; Setodeh, Ramin; Riley, Jenelle; Gleiberman, Owen; Debruge, Peter (April 28, 2021). "After Oscars Ratings Tank, Do the Academy Awards Need Another Makeover?". Variety. Archived from the original on May 3, 2021. Retrieved June 19, 2021.

- ^ a b "Oscars 2021: Audiences Turn Away As a Sluggish Ceremony Leaves Critics Cold". BBC News. April 26, 2021. Archived from the original on August 4, 2021. Retrieved July 13, 2021.

- ^ Siegel, Tatiana; Lewis, Hilary; Konerman, Jennifer; Nordyke, Kimberly (March 15, 2021). "Oscars: 'Mank' Leads Nominees With 10". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on May 5, 2021. Retrieved March 19, 2021.

- ^ "'Nomadland' Wins Best Picture, and Other Highlights from the 2021 Academy Awards". Tampa Bay Times. April 25, 2021. Archived from the original on April 29, 2021. Retrieved April 30, 2021.

- ^ Barnes, Brooks; Sperling, Nicole (April 25, 2021). "'Nomadland' Makes History, and Anthony Hopkins, in Upset, Wins Best Actor". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 27, 2021. Retrieved April 26, 2021.

- ^ Stevens, Matt (April 26, 2021). "Anthony Hopkins shocks by winning best actor over Chadwick Boseman". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 26, 2021. Retrieved April 26, 2021.

- ^ Lindahl, Chris (April 25, 2021). "Frances McDormand Wins Best Actress: Third Career Oscar, Only Katharine Hepburn Won More in Category". IndieWire. Archived from the original on April 26, 2021. Retrieved April 26, 2021.

- ^ Harris, Beth (April 26, 2021). "Frances McDormand a double Oscar winner for 'Nomadland'". Associated Press. Archived from the original on April 26, 2021. Retrieved April 26, 2021.

- ^ Barnes, Brooks; Sperling, Nicole (April 25, 2021). "'Nomadland' Makes History, and Anthony Hopkins, in Upset, Wins Best Actor". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 27, 2021. Retrieved June 19, 2021.

- ^ Grain, Paul (April 6, 2021). "Six Oscar Nominees Who Set New Records for Song and Score". Billboard. Archived from the original on April 2, 2021. Retrieved April 12, 2021.

- ^ "The 93rd Academy Awards | 2021". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on March 15, 2021. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- ^ Jackson, Angelique (April 21, 2021). "Oscars Big Week: Tyler Perry and Motion Picture & Television Fund To Receive Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award". Variety. Archived from the original on April 26, 2021. Retrieved April 25, 2021.

- ^ Wloszczyna, Susan (April 26, 2021). "Oscars 2021: Nomadland is the Big Winner at an Unusual Academy Awards". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on June 24, 2021. Retrieved June 3, 2021.

- ^ Kemp, Ella (April 26, 2021). "Oscars 2021 Live Blog". Empire. Archived from the original on May 17, 2021. Retrieved May 23, 2021.

- ^ Hipes, Patrick (April 4, 2017). "Oscars Dates Set For 2018 And Beyond". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on April 5, 2017. Retrieved June 22, 2020.

- ^ Malkin, Marc (June 15, 2020). "Oscars 2021 Pushed Back by Two Months". Variety. Archived from the original on June 16, 2020. Retrieved September 19, 2020.

- ^ Pond, Steve (March 15, 2021). "Academy Limits Oscars to Nominees and Their Guests, Cancels Governors Ball and Nominees Lunch". TheWrap. Archived from the original on June 3, 2021. Retrieved May 30, 2021.

- ^ Finn, Natalie (April 26, 2021). "The 7 Biggest Jaw-Droppers at the 2021 Oscars". E!. Archived from the original on June 24, 2021. Retrieved June 17, 2021.

- ^ Martinez, Peter (June 15, 2020). "Next Year's Oscars Delayed to April 25 Due to the Coronavirus Pandemic". CBS News. Archived from the original on August 8, 2020. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- ^ Hammond, Pete (December 8, 2020). "Oscars: Steven Soderbergh, Stacey Sher & Jesse Collins To Produce 93rd Academy Awards". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on December 28, 2020. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

- ^ Hipes, Patrick (March 11, 2021). "Oscars Poster Revealed With This Year's Tagline "Bring Your Movie Love"; No Clues Offered About Ceremony". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on June 24, 2021. Retrieved June 19, 2021.

- ^ Pond, Steve (March 11, 2021). "Oscars Unveil Poster Created by Artists From Around the World". TheWrap. Archived from the original on June 24, 2021. Retrieved May 19, 2021.

- ^ Hammond, Pete (April 12, 2021). "Oscars: Academy Sets Ensemble Cast Of 15 Stars To Serve As Presenters". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on April 17, 2021. Retrieved April 12, 2021.

- ^ a b Hammond, Pete (March 18, 2021). "Oscar Show Takes Shape With Letter To Nominees: No Zooms, No Casual Dress, Covid Protocols In Force & "Stories Matter"". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on March 23, 2021. Retrieved March 22, 2021.

- ^ Van Syckle, Katie (April 22, 2021). "Preparing for a Surreal Oscar Night". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 25, 2021. Retrieved April 26, 2021.

- ^ Maddus, Gene (March 15, 2021). "Oscars to Broadcast From L.A.'s Union Station and Dolby Theatre". Variety. Archived from the original on March 24, 2021. Retrieved March 25, 2021.

- ^ Feinberg, Scott (March 15, 2021). "Oscars: Only Presenters, Nominees and Guests Will Attend In-Person". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on June 24, 2021. Retrieved April 12, 2021.

- ^ Rottenberg, Josh (April 25, 2021). "Masks at the Oscars? Here's How the Academy Awards are Happening in Person". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 16, 2021. Retrieved May 16, 2021.

- ^ Malkin, Marc (April 19, 2021). "Oscar Attendees Will Not Wear Face Masks During Telecast (Exclusive)". Variety. Archived from the original on April 22, 2021. Retrieved May 20, 2021.

- ^ Hammond, Pete (March 30, 2021). "Oscars: Academy To Create European Hub(s) For Nominees Unable To Travel To U.S.; Producers Reveal New Details On Show". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on April 10, 2021. Retrieved April 12, 2021.

- ^ Ravindran, Manori (April 14, 2021). "Oscars in London: BFI Southbank Confirmed as U.K. Hub For Ceremony (Exclusive)". Variety. Archived from the original on April 23, 2021. Retrieved May 7, 2021.

- ^ Aswad, Jem (April 21, 2021). "How Questlove and Oscars Producer Jesse Collins Are Changing Music at the 2021 Academy Awards". Variety. Archived from the original on April 25, 2021. Retrieved April 25, 2021.

- ^ Welk, Brian (April 22, 2021). "'West Side Story,' 'In the Heights,' 'Summer of Soul' Trailers to Debut During Oscars". TheWrap. Archived from the original on April 23, 2021. Retrieved April 22, 2021.

- ^ D'Alessandro, Anthony (April 22, 2021). "Disney To Celebrate Moviegoing During Oscars With Talent & Exclusive Trailers From 'West Side Story', 'Summer Of Soul' & More". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on April 23, 2021. Retrieved April 22, 2021.

- ^ Tangcay, Jazz (April 21, 2020). "Oscars 2021: How Designer David Rockwell Will Transform Union Station". Variety. Archived from the original on April 28, 2021. Retrieved May 13, 2021.

- ^ "Oscars Set Revealed: Here's How L.A.'s Union Station Will Get Gussied Up – Photo Gallery". Deadline Hollywood. April 21, 2021. Archived from the original on April 22, 2021. Retrieved April 23, 2021.

- ^ Tangcay, Jazz (April 21, 2021). "Oscars 2021: How Designer David Rockwell Will Transform Union Station". Variety. Archived from the original on April 28, 2021. Retrieved May 21, 2021.

- ^ Welk, Brian (April 16, 2021). "Oscars Song Contenders to Perform for Pre-Show, 'After Dark' Special Set for Post-Awards". TheWrap. Archived from the original on April 26, 2021. Retrieved April 26, 2021.

- ^ White, Abbey (March 25, 2022). "Oscars Telecast Will Feature Free Live ASL Interpretation on The Academy's YouTube Channel". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on March 27, 2022. Retrieved March 29, 2022.

- ^ Sun, Rebecca (April 26, 2021). "Oscars Diversity: Historic Firsts for Non-Acting Categories and Ceremony Accessibility". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on March 29, 2022. Retrieved March 29, 2022.

- ^ "Marlee Matlin on 'CODA' & Fighting for Deaf Stories". Backstage. January 4, 2022. Archived from the original on December 4, 2021. Retrieved March 28, 2022.

- ^ Barnes, Brooks (June 15, 2020). "The 2021 Oscars Will Be Delayed". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 21, 2020. Retrieved August 13, 2020.

- ^ Feinberg, Scott (April 28, 2020). "Oscars During Coronavirus: Academy Rules Streamed Films Eligible, Merges Sound Categories". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on June 24, 2021. Retrieved June 19, 2020.

- ^ Mandell, Andrea; Alexander, Bryan (October 7, 2020). "Academy Makes Major Change: Drive-in Movies Can Now Qualify for 2021 Oscars". USA Today. Archived from the original on November 6, 2020. Retrieved November 17, 2020.

- ^ Ordoña, Michael (April 28, 2020). "Just One Oscar Category for Sound? The Pros Are Happy to Share the Acclaim". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 21, 2020. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- ^ Grein, Paul (April 28, 2020). "Oscars Extend Eligibility to Streamed Films Amid Coronavirus Pandemic". Billboard. Archived from the original on June 4, 2020. Retrieved June 29, 2020.

- ^ Hammond, Pete (April 28, 2020). "Oscars Keeping Show Date But Make Big News As Academy Lightens Eligibility Rules, Combines Sound Categories, Ends DVD Screeners and More". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on May 23, 2020. Retrieved May 6, 2020.

- ^ Vary, Adam B. (April 25, 2021). "Oscars End Abruptly with Anthony Hopkins Best Actor Upset". Variety. Archived from the original on April 26, 2021. Retrieved April 30, 2021.

- ^ a b Jackson, Angelique (April 26, 2021). "Anthony Hopkins Pays Tribute to Chadwick Boseman After Surprise Second Oscar Win". Variety. Archived from the original on July 10, 2021. Retrieved July 2, 2021.

- ^ a b c Buchanan, Kyle (April 26, 2021). "Inside Anthony Hopkins's Unexpected Win at the Oscars". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 15, 2021. Retrieved May 23, 2021.

- ^ Drury, Sharareh (April 26, 2021). "Oscars Face Backlash Over Chadwick Boseman Snub". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on April 2, 2022. Retrieved April 2, 2022.

- ^ Romero, Ariana. "Chadwick Boseman Loses Best Actor In Shocking Oscars Finale". www.refinery29.com. Archived from the original on April 2, 2022. Retrieved April 2, 2022.

- ^ Sharf, Zack (April 27, 2021). "Chadwick Boseman's Family Speaks Out on Oscars Loss: This Was Not a Snub". IndieWire. Archived from the original on April 2, 2022. Retrieved April 2, 2022.

- ^ "That off-key Oscars ending? Had to be done, says producer Steven Soderbergh". Los Angeles Times. May 4, 2021. Archived from the original on May 13, 2021. Retrieved May 13, 2021.

- ^ "The Academy Awards: 93rd Oscars". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved March 15, 2024.

- ^ Hale, Mike (April 25, 2021). "The Covid-19 Oscars: Not Masked but Still Muffled". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 9, 2021. Retrieved May 9, 2021.

- ^ Sheffield, Rob (April 25, 2021). "Oscars 2021: Wolf Howls, Da Butt and the Chadwick Boseman Tribute That Wasn't". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on May 4, 2021. Retrieved May 17, 2021.

- ^ Lawler, Kelly (April 26, 2021). "How the First (and Hopefully Last) Pandemic Oscars Went So Terribly Wrong". USA Today. Archived from the original on May 31, 2021. Retrieved May 23, 2021.

- ^ Berman, Judy (April 26, 2021). "The Pandemic Oscars Were Surprisingly Decent. But Will the Academy Learn Anything From Its Break With Tradition?". Time. Archived from the original on April 29, 2021. Retrieved May 31, 2021.

- ^ Bahr, Lindsey (April 25, 2021). "Review: Not Quite a Movie, but the Oscars Were a Love Letter". Associated Press. Archived from the original on June 2, 2021. Retrieved May 31, 2021.

- ^ Franlch, Darren (April 25, 2021). "What a Weird Oscars: Review". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on May 21, 2021. Retrieved May 25, 2021.

- ^ Richwine, Lisa; Grebler, Dan (April 27, 2021). "Final TV ratings for Oscars inch up to 10.4 million viewers". Reuters. Archived from the original on June 24, 2021. Retrieved June 19, 2021.

- ^ Whitten, Sarah (May 2, 2021). "Audiences for Award Shows are in Steep Decline; This Chart Shows How Far Viewership Has Fallen". CNBC. Archived from the original on May 19, 2021. Retrieved May 19, 2021.

- ^ Smith, Gerry (April 26, 2021). "Oscars Audience Collapses in Latest Setback for Awards Shows". Bloomberg Businessweek. Archived from the original on April 29, 2021. Retrieved June 19, 2021.

- ^ Goldberg, Leslie (July 13, 2021). "Emmys: Disney Leads All Combined Nominations as HBO (Thanks to HBO Max) Tops Netflix". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on October 11, 2021. Retrieved September 19, 2021.

- ^ Pedersen, Erik (September 12, 2021). "Creative Arts Emmys: Complete Winners List For All Three Ceremonies". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on September 12, 2021. Retrieved November 11, 2021.

- ^ "Chloé Zhao's historic win at this year's Oscars censored in China". South China Morning Post. April 26, 2021. Archived from the original on October 7, 2021. Retrieved April 27, 2021.

- ^ Lin, Liza (April 26, 2021). "China Censors 'Nomadland' Director Chloé Zhao's Oscar Win". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on April 29, 2021. Retrieved April 26, 2021.

- ^ "Oscars won't show in Hong Kong for first time since 1969 as state media rails against protest film nomination". Hong Kong Free Press. April 25, 2021. Archived from the original on March 22, 2023. Retrieved April 26, 2021.

- ^ D'Zurilla, Christine (April 26, 2021). "Another Oscars, Another Round of In Memoriam Snubs: Where Was Adam Schlesinger?". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 11, 2021. Retrieved June 12, 2021.

- ^ Gittins, William (April 24, 2021). "In Memoriam Oscars 2021: directors, actors and writers who died in 2020". Diario AS. Archived from the original on April 25, 2021. Retrieved April 27, 2021.

- ^ Klnane, Ruth (April 25, 2021). "Chadwick Boseman, Christopher Plummer, Sean Connery Featured in Oscars in Memoriam Tribute". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on June 13, 2021. Retrieved June 12, 2021.

External links[edit]

Official websites

- Academy Awards official website

- The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences official website

- Oscars channel at YouTube (run by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences)

News resources

Other resources

- 2020 film awards

- 2021 awards in the United States

- 2021 film awards

- 2021 in Los Angeles

- 2021 television specials

- Academy Awards ceremonies

- April 2021 events in the United States

- Events postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic

- Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cinema

- Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on television

- Television shows directed by Glenn Weiss