List of African-American historic places

| Part of a series on |

| African Americans |

|---|

The following is a dynamic and expanding list of African-American historic places in the United States and territories which have been documented to be of significance to illustrating the experience of the African diaspora in America. Some are local landmarks while others are on the National Register of Historic Places.[1] The stories of the contributions, hardships, and aspirations of all American people can be seen in the experiences of African Americans at these physical locations.[2] The formal preservation of these sites dates back to at least 1917 according to architectural historian Brent Leggs when efforts to save the Gothic Revival home of abolitionist and statesman Frederick Douglass were launched. "Even when it wasn't called 'preservation,' this work was already happening."[1]

The places listed below represent the achievements and struggles of African Americans. Visitors to these sites can gain a better understanding of the events and the people of that time. These places connected across time to create an understanding of what happened and why.[3]

African-American historic places organized by period or topic[edit]

This outline has been adapted from other related Wikipedia articles and The Negro Pilgrimage in America by C. Eric Lincoln and Before the Mayflower; A History of the Negro in America; 1619-1964 by Lerone Bennett Jr.

Origins [4]

This article needs to be updated. (July 2020) |

The Negro Pilgrimage in America[4] or the African Past[5] The story of the African Americans begins in Africa. Early histories of Africa considered it the 'Dark Continent', both in the sense of the color of its people, but also for its lack of known civilizations. Studies beginning in the 1960s have found a rich history of civilization, including arts, architecture, public thought and major civilizations.[5] The story of African Americans builds from these roots and can be traced through historic sites associated with the slave trade in America:[2]

- Charlotte Amalie Historic District – Virgin Islands

- Fairvue - Kentucky

- The Grange

- Kingsley Plantation

- Old Slave Mart – South Carolina

American Revolution [5]

While the term 'American Revolution' connotes only the war period (1776–1783), the entire colonial experience is included. Free Negros were present during early campaigns of the war and throughout the war. In March 1770, Crispus Attucks died during the protest that has become known as the Boston Massacre.[5] At the Battle of Bunker Hill, Peter Salem and Salem Poor, two free Negros valiantly served. Salem Poor was commended for his actions that day.[5]

- Burns United Methodist Church

- Christiansted National Historic Site

- Hacienda Azucarera La Esperanza – Puerto Rico

- Hawikuh

- Jack Peterson Memorial, Croton-on-Hudson, New York

For over 200 years, the American system of slavery held four million people of color in bondage.[5] The effect was felt by all the people of the nation, including black, white, yellow, and red. It was premised on a system of racial supremacy that affected the development of the American Negro and the relationships of all American's with persons of other races.[5]

The first blacks in the new world did not arrive on the slave ship to Jamestown in 1619. Rather, it was Pedro Alonzo Niño, navigator on the Niña the smallest of Christopher Columbus's vessels.[4] From that day, Negros participated in nearly every major Spanish exploration in the new world. Neflo de Olaña and thirty other Negros were with Balboa when they discovered the Pacific Ocean.[4]

- Antioch Missionary Baptist Church – Richard Allen (organized the AME church)

- Jean Baptiste Point Du Sable Homesite – Jean Baptiste Point du Sable (1st settler of Chicago)

- First African Baptist Church, Richmond, Virginia

- Lumpkin's Jail, Richmond, Virginia

- Hacienda Azucarera La Esperanza – Puerto Rico

- Hawikuh – Estevanico

- Prince Hall Masonic Temple – Prince Hall (organized 1st Negro Masonic Lodge)

Slave revolts and insurrections[5]

In the summer of 1791, Haiti witnessed the first successful slave revolt. This was not the first; it was one in a long series of revolts.[5] Between 1663 and 1864, there were 109 revolts on land and another 55 at sea.[4] Notable early insurrections include the 1712 uprising in New York City and the 1800 attack on Richmond, Virginia known as Gabriel's Rebellion. That same year, Denmark Vesey, a free black, planned to seize Charleston, South Carolina, but was foiled when betrayed.[4]

- Belmont – Virginia

- John Brown Farm – John Brown's birthplace. - New York

- John Brown House - New York

- John Brown Headquarters – Headquarters for the Harper's Ferry Raid

- Estate Carolina Sugar Plantation

- Stono River Slave Rebellion – Site of the 1739 Stono Rebellion - South Carolina.

Abolition crisis[4]

With the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, the United States gained a huge western dominion. With it, two aspects of American life came into stark comparison. The first was the expansion of slavery across the southern half of the nation, creating a vast agricultural empire based on a large rural workforce. The second was Manifest Destiny, the expansion of a free society westward across the continent.[4] The economic realities in the south precluded the development of a strong abolitionist base, while the lack of slavery among the industrialized north, neither supported nor abhorred the abolitionist cause.[4] By 1835, William Lloyd Garrison had established The Liberator as the nation's most militant abolitionist newspaper. Over the next 30 years, the north and the south would try to find ways to coexist with two different economic systems and a growing abolitionist movement.[5]

Frederick Douglass National Historic Site, Washington, D.C. - Levi Coffin House – Fountain City, Indiana

- Frederick Douglass National Historic Site – Washington D.C.

- Eleutherian College – Lancaster, Indiana

- Harpers Ferry National Historical Park – West Virginia

- Little Jerusalem AME Church – Cornwells Heights-Eddington, Pennsylvania

- William C. Nell House – Boston, Massachusetts

- Harriet Beecher Stowe House – Brunswick, Maine

- Liberty Farm – Worcester, Massachusetts

- Mount Zion United Methodist Church-Washington, D.C.

- White Horse Farm-Phoenixville, Pennsylvania

Civil war and emancipation[4][5]

The American Civil War is often seen as a war between white men over the fate of the black man. From the beginning, the African-American peoples played a significant role in the war.[5] As early as July 1861, three months after Fort Sumter, the United States Congress passed the first Confiscation Act, granting freedom to any slave who had been used to support the Confederate war efforts, once they were behind Union Lines.[4] Quickly General Sherman employed this new manpower in the construction of Union facilities from which to prosecute the war.[4] With the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation on September 22, 1862, the First Regiment Louisiana Heavy Artillery and All Negro unit was founded by General B.F. Butler. The War Department quickly authorized the enlistment of Negro soldier with the founding of the Massachusetts Fifty-Fourth and Fifty-Fifth Infantry Regiments. By the end of the war, there were over 150 all-Negro regiments.[4] On September 29, 1864, the Third Division of the Eighteenth Corp of the Army of the James, moved forward to take the New Market Heights outside Richmond, Virginia. The key role in this advance was given to the 'all-Negro' division. By the end of the day, the Union Army would stand on the heights overlooking the city of Richmond with a loss of 584 men and 10 Congressional Medal honorees now in their ranks. This action marked the beginning of the dissolution of the Confederate Government and the end of the war the following April.

Robert Gould Shaw Memorial, Boston African American National Historic Site, Boston, MA - Camilla-Zack Community Center District – Mayfield, Georgia

- Fort Pillow – Tennessee

- Goodwill Plantation – Eastover, South Carolina

- John Mercer Langston House – Oberlin, Ohio

- Lewis O'Neal Tavern – Versailles, Kentucky

- Oakview – Holly Springs, Mississippi

- Olustee Battlefield – Olustee, Florida

- Port Hudson – Port Hudson, Louisiana

- Seaside Plantation-Beaufort, South Carolina

- Slate Hill Cemetery-Morrisville, Pennsylvania

- Sulphur Trestle Fort Site – Elkmont, Alabama

- Alcorn State University Historic District – Lorman, Mississippi

- Barber House – Hopkins, South Carolina

- Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church – Batesville, Arkansas

- Clarksville Historic District – Lancaster, Indiana

- Daufuskie Island Historic District – South Carolina

- Fair-Rutherford and Rutherford Houses – Columbia, South Carolina

- Freeman Chapel C.M.E. Church – Hopkinsville, Kentucky

- Laurel Grove-South Cemetery – Savannah, Georgia

- Lincoln University Hilltop Campus Historic District – Jefferson City, Missouri

- Ploeger-Kerr-White House-Bastrop, Texas

- Springfield Baptist Church-Greensboro, Georgia

- Stone Hall, Atlanta University – Atlanta, Georgia

- Charles Sumner High School – St. Louis, Missouri

- Lyman Trumbull House – Alton, Illinois

- Working Benevolent Temple and Professional Building – Greenville, South Carolina

Segregation[4] and the rise of Jim Crow[5]

- Wililam R. Allen School – Lorman, Mississippi

- Black Theater of Ardmore – Ardmore, Oklahoma

- Davis Avenue Branch, Mobile Public Library – Mobile, Alabama

- Fairbanks Flats – Lancaster, Indiana

- Fourth Avenue Historic District – Birmingham, Alabama

- Indiana Avenue Historic District – Indianapolis, Indiana

- Main Building, Arkansas Baptist College – Hopkinsville, Arkansas

- Smithfield Historic District – Savannah, Georgia

- Sweet Auburn Historic District – Atlanta, Georgia

- Tenth Street Freedman's Town – Dallas, Texas

- Ward Chapel AME Church – Muscogee, Oklahoma

Northern Migration [4]

- Chicago Bee Building – Chicago, Illinois

- Robert S. Abbott House – Chicago, Illinois

- Bethany Baptist Church – Chislehurst, New Jersey

- Durham Memorial A.M.E. Zion Church – Buffalo, New York

- Langston Terrace Dwellings – Washington, D.C.

- Liberty Baptist Church – Evansville, Indiana

- Wabash Avenue YMCA – Chicago, Illinois

Expanding opportunities [4]

- Alcorn State University Historic District – Lorman, Mississippi

- Barber House – Hopkins, South Carolina

- Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church – Batesville, Arkansas

- Clarksville Historic District – Lancaster, Indiana

- Daufuskie Island Historic District – South Carolina

- Fair-Rutherford and Rutherford Houses – Columbia, South Carolina

- Freeman Chapel C.M.E. Church – Hopkinsville, Kentucky

- Laurel Grove-South Cemetery – Savannah, Georgia

- Lincoln University Hilltop Campus Historic District – Jefferson City, Missouri

- Ploeger-Kerr-White House,-Bastrop, Texas

- Springfield Baptist Church-Greensboro, Georgia

- Stone Hall, Atlanta University – Atlanta, Georgia

- Charles Sumner High School – St. Louis, Missouri

- Lyman Trumbull House – Alton, Illinois

- Working Benevolent Temple and Professional Building – Greenville, South Carolina

- 16th Street Baptist Church - Birmingham, Alabama

- Agricultural and Technical College of North Carolina Historic District – Greensboro, North Carolina

- Brown Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Church – Selma, Alabama

- City of St. Jude Historic District – Montgomery, Alabama

- Dexter Avenue Baptist Church – Montgomery, Alabama

- First African Baptist Church – Tuscaloosa, Alabama

- Martin Luther King Jr. Historic District – Atlanta, Georgia

- Lincolnville Historic District – St. Augustine, Florida

- Little Rock Central High School – Little Rock, Arkansas

- Malcolm X House Site – Omaha, Nebraska

- Howard Thurman House-Daytona Beach, Florida

- Dr. Cyril O. Spann Medical Office- Columbia, South Carolina

Cemeteries

The preservation of African-American cemeteries is an integral part of documenting Black history and heritage. Many lands where enslaved or freed black individuals were buried are threatened by development and neglect though new efforts are underway to protect these historic places.[6]

- African Burial Ground National Monument, New York, New York

- African Jackson Cemetery, Piqua, Ohio

- Barton Heights Cemeteries, city of Richmond, Virginia

- East End Cemetery, city of Richmond, Virginia

- Eden Cemetery, Collingdale, Pennsylvania

- Evergreen Cemetery, city of Richmond, Virginia

- Gethsemane Cemetery, Little Ferry, New Jersey

- Gospel Pilgrim Cemetery, Athens, Georgia

- Gower Cemetery, Edmond, Oklahoma

- Hampton Springs Cemetery (Black Section), Carthage, Arkansas

- Harlem African Burial Ground, New York, New York

- Laurel Grove Cemetery – Savannah, Georgia

- Lebanon Cemetery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

- Magnolia Cemetery including Mobile National Cemetery, Mobile, Alabama

- Mount Pisgah Benevolence Cemetery, Romney, West Virginia

- Newburgh Colored Burial Ground, Newburgh, New York

- New Hope Missionary Baptist Church Cemetery, Historic Section, Lake Village, Arkansas

- Portsmouth African Burying Ground, Portsmouth, New Hampshire

- Rye African-American Cemetery, Rye, New York

- Saint Paul's Church National Historic Site, Mount Vernon, New York

- Shockoe Bottom African Burial Ground - city of Richmond, Virginia

- Shockoe Hill African Burying Ground, city of Richmond, Virginia

- Slate Hill Cemetery, Morrisville, Pennsylvania

- St. David African Methodist Episcopal Zion Cemetery, Sag Harbor, New York

- Stony Hill Cemetery, Harrison, New York

- Toussaint L'Ouverture County Cemetery, Tennessee

African-American historic places organized by state or territory[edit]

Alabama[edit]

- 16th Street Baptist Church, Birmingham

- Alabama Penny Savings Bank, Birmingham

- Brown Chapel A.M.E. Church, Selma

- Butler Chapel AME Zion Church, Greenville

- Calhoun School Principal's House, Calhoun

- City of St. Jude Historic District, Montgomery

- Dave Patton House, Mobile

- Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, Montgomery

- Domestic Science Building, Normal

- Dr. A.M. Brown House, Birmingham

- Ebenezer Missionary Baptist Church, Auburn

- Emanuel AME Church, Mobile

- First African Baptist Church, Tuscaloosa

- First Baptist Church, Greenville

- First Baptist Church, Selma

- First Congregational Church of Marion, Marion

- Fourth Avenue Historic District, Birmingham

- Hawthorn House, Mobile

- Hunter House, Mobile

- Jefferson Franklin Jackson House, Montgomery

- West Park, Birmingham

- Laura Watson House, Gainesville

- Lebanon Chapel AME Church, Fairhope

- Magnolia Cemetery, including Mobile National Cemetery, Mobile

- Mount Zion Baptist Church, Anniston

- Murphy-Collins House, Tuscaloosa

- Davis Avenue Branch, Mobile Public Library, Mobile

- North Lawrence-Monroe Street Historic District, Montgomery

- Old Ship African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, Montgomery

- Pastorium, Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, Montgomery

- Phillips Memorial Auditorium, Marion

- Pratt City Carline Historic District, Birmingham

- Rickwood Field, Birmingham

- Searcy Hospital, Mount Vernon

- Smithfield Historic District, Birmingham

- St. Louis Street Missionary Baptist Church, Mobile

- State Street AME Zion Church, Mobile

- Stone Street Baptist Church, Mobile

- Sulphur Trestle Fort Site, Elkmont

- Swayne Hall, Talladega

- Talladega College Historic District, Talladega

- Theological Building- AME Zion Theological Institute, Greenville

- Tulane Building, Montgomery

- Tuskegee Institute National Historic Site, Tuskegee

- Twin Beach AME Church, Fairhope

- Ward Nicholson Corner Store, Greenville

- West Fifteenth Street Historic District, Anniston

- Westwood Plantation (Boundary Increase), Uniontown

- Windham Construction Office Building, Birmingham

Arizona[edit]

- Phoenix Union Colored High School, Phoenix

Arkansas[edit]

- Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church, Batesville

- Dunbar Junior and Senior High School and Junior College, Little Rock

- Hampton Springs Cemetery (Black Section), Carthage

- Henry Clay Mills House, Van Buren

- Ish House, Little Rock

- Kiblah School, Doddridge

- Little Rock High School, Little Rock

- Main Building, Arkansas Baptist College, Little Rock

- Mosaic Templars of America Headquarters Building, Little Rock

- Mount Olive United Methodist Church, Van Buren

- Mount Zion Missionary Baptist Church, Brinkley

- New Hope Missionary Baptist Church Cemetery, Historic Section, Lake Village

- Taborian Hall, Little Rock

- Wortham Gymnasium, Oak Grove

California[edit]

Allensworth Historic District, Allensworth, CA - Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church, San Francisco

- California State Convention of Colored Citizens

- First African Methodist Episcopal Church of Los Angeles, Los Angeles

- Liberty Hall, Oakland

- Moses Rodgers House, Stockton

- Somerville Hotel, Los Angeles

- Sugg House, Sonora

Colorado[edit]

- Barney L. Ford Building, Denver

- Justina Ford House, Denver

- Winks Panorama, Pinecliffe

- Earl School, a rare example of a building associated with rural African-Americans in Colorado, of a farming homestead colony.

Connecticut[edit]

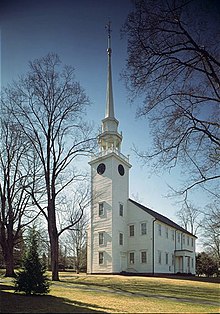

- First Church of Christ, Farmington

- Goffe Street Special School for Colored Children, New Haven

- Lighthouse Archeological Sites, Barkhamstead

- Mary and Eliza Freeman Houses, Bridgeport

- Mather Homestead, Hartford

- Prudence Crandall House, Canterbury

Delaware[edit]

- Harmon School, Millsboro

- Johnson School, Millsboro

- Lewes Historic District, Lewes

- Loockeman Hall, Dover

- Odessa Historic District, Odessa

- Old Fort Church Christiana

- Public School No. 111-c, Christiana

- Smyrna Historic District, Smyrna

District of Columbia[edit]

Florida[edit]

Georgia[edit]

- Gospel Pilgrim Cemetery, Athens

Hawaii[edit]

- African American Diversity Cultural Center

Idaho[edit]

Illinois[edit]

- Christian Hill Historic District, Alton

- Dr. Daniel Hale Williams House, Chicago

- Eighth Regiment Armory, Chicago

- New Philadelphia Town Site / Free Frank McWorter Grave Site, Barry

- Ida B. Wells-Barnett House, Chicago

- Jean Baptiste Point Du Sable Homesite, Chicago

- Lyman Trumbull House, Alton

- Overton Hygienic Building, Chicago

- Owen Lovejoy Homestead, Princeton

- Quinn Chapel of the AME Church, Chicago

- Robert S. Abbott House, Chicago

- Unity Hall, Chicago (located in the Black Metropolis-Bronzeville District of Chicago)

- Victory Sculpture, Chicago

- Wabash Avenue YMCA, Chicago

Indiana[edit]

- Allen Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Church, Terre Haute

- Bethel AME Church, Franklin

- Booker T. Washington School, Rushville

- Crispus Attucks High School, Indianapolis

- Eleutherian College, Lancaster

- Iddings-Gilbert-Leader-Anderson Block, Kendallville

- Indiana Avenue Historic District, Indianapolis

- J. Woodrow Wilson House, Marion

- Levi Coffin House, Fountain City (NHL)

- Liberty Baptist Church, Evansville

- Lockefield Garden Apartments, Indianapolis

- Madame C. J. Walker Building, Indianapolis

- Minor House, Indianapolis

- Old Richmond Historic District, Richmond

- Ransom Place Historic District, Indianapolis

- Rockville Historic District, Rockville

- St. Augustine's Episcopal Church, Gary

- Theodore Roosevelt High School (Gary)

Iowa[edit]

Alexander Clark House, Muscatine, IA - Bethel AME Church, Cedar Rapids

- Bethel AME Church, Davenport

- Bethel AME Church, Iowa City

- Burns United Methodist Church, Des Moines

- Buxton Historic Townsite, Lovilia

- Fort Des Moines Provisional Army Officer Training School, Des Moines

- Second Baptist Church, Centerville

Kansas[edit]

Brown v. Board of Education National Historic Site, Topeka, KS - John Brown Cabin. Osawatomie

- George Washington Carver Homestead Site, Beeler

- Arkansas Valley lodge No. 21, Prince Hall Masons, Wichita

- Calvary Baptist, Wichita

- Brown v. Board of Education National Historic Site, Topeka

Kentucky[edit]

First African Baptist Church, Lexington, KY - Abner Knox farm, Danville

- Anderson House, Haskingsville

- Andrew Muldrow Quarters, Tyrone

- Artelia Anderson Hall, Paduch

- Ash Emison Quarters, Delaplain

- Bayless Quarters, North Middletown

- Bethel AME Church, Shelbyville

- Bloomfield Historic District, Bloomfield

- Broadway Temple AME Zion Church, Louisville

- Central Colored School, Louisville

- Chandler Normal School Building and Webster Hall, Lexington

- Charity's House, Falmouth

- Chestnut Street Baptist Church, Louisville

- Church of Our Merciful Saviour, Louisville

- E.E. Hume Hall, Frankfort

- Embry Chapel Church, Elizabethtown

- Emery-Price Historic District, Covington

- First African Baptist Church and Parsonage, Georgetown

- First African Baptist Church, Lexington

- First Baptist Church, Elizabethtown

- First Baptist Church, Frankfort

- First Colored Baptist Church, Bowling Green

- Freeman Chapel C.M.E. Church, Hopkinsville

- Hogan Quarters, Versailles

- Jackson Hall, Kentucky State University, Frankfort

- James Briscoe Quarters, Delaplain

- Jeffersontown Colored School, Jeffersontown

- John Leavell Quarters, Bryantville

- Johnson's Chapel AME Zion Church, Springfield

- Johnson-Pence House, Georgetown

- Joseph Patterson Quarters, Midway

- KEAS Tabernacle Christian Methodist Episcopal Church, Mount Sterling

- Knights of Pythias Temple, Louisville

- Lewis O'Neal Tavern, Versailles

- Limerick Historic District (Boundary Increase), Louisville

- Lincoln Hall, Berea

- Lincoln Institute Complex, Simpsonville

- Lincoln School, Paduch

- Louisville Free Public Library, Western Colored Branch, Louisville

- Meriwether House, Louisville

- Midway Historic District, Midway

- Minor Chapel AME Church, Taylorsville

- Mount Vernon AME Church, Gamaliel

- Mt. Moriah Baptist Church, Middleboro

- Municipal College Campus, Simmons University, Louisville

- Old Statehouse Historic District, Frankfort

- Perry Shelburne House, Taylorsville

- Pisgah Rural Historic District, Lexington/Versailles

- Poston House, Hopkinsville

- Reed Road Rural Historic District, Lexington

- Russell Historic District, Louisville

- Solomon Thomas House, Salvisa

- South Frankfort Neighborhood Historic District, Frankfort

- St. James AME Church, Ashland

- St. John United Methodist Church, Shelbyville

- Stone Barn on Brushy Creek, Carlisle

- Stone Quarters on Burgin Road, Harrodsburg

- The Grange, Paris

- Thomas Chapel C.M.E. Church, Hickman

- Union Station School, Paducah

- University of Louisville Belknap Campus, Louisville

- Whitney M. Young, Jr., Birthplace, Simpsonville

Louisiana[edit]

Congo Square, New Orleans, LA - Badin-Roque House, Natchez

- Canebrake, Ferriday

- Carter Plantation, Springfield

- Central High School, Shreveport

- Congo Square, New Orleans

- Evergreen Plantation, Wallace

- Fazendeville, St. Bernard Parish

- Flint-Goodridge Hospital of Dillard University, New Orleans

- Holy Rosary Institute, Lafayette

- James H. Dillard House, New Orleans

- Kenner and Kugler Cemeteries Archeological District, Norco

- Leland College, Baker

- Magnolia Plantation, Derry

- Maison de Marie Therese, Bermuda

- McKinley High School, Baton Rouge

- Melrose Plantation, Melrose

- Port Hudson, Port Hudson

- Southern University Archives Building, Scotlandville

- St. James AME Church, New Orleans

- St. Joseph Historic District, St. Joseph

- St. Joseph's School (Burnside, Louisiana)

- St. Paul Lutheran Church, Mansura

- St. Peter AME Church, New Orleans

- Tangipahoa Parish Training School Dormitory, Kentwood

Maine[edit]

- Green Memorial AME Zion Church, Portland

- John B. Russwurm House, Portland

- Harriet Beecher Stowe House, Brunswick

- Abyssinian Meeting House, Portland

- Malaga Island, Phippsburg

Maryland[edit]

L'Hermitage Slave Village Archeological Site, Frederick, MD - Berkley School, Darlington

- Don S.S. Goodloe House, Bowie

- Douglass Place, Baltimore

- Douglass Summer House, Highland Beach

- Eagle Harbor

- Frederick Douglass High School, Baltimore

- Grassland, Annapolis Junction

- John Brown's Headquarters, Samples Manor

- Jonestown, Howard County

- L'Hermitage Slave Village Archeological Site, Frederick

- McComas Institute, Joppa

- Mt. Gilboa Chapel, Oella

- Mt. Moriah African Methodist Episcopal Church, Annapolis

- Orchard Street United Methodist Church, Baltimore

- Public School No. 111, Baltimore

- Snow Hill Site, Port Deposit Archeological site.

- St. John's Church, Ruxton

- Stanley Institute, Cambridge

- Stanton Center, Annapolis

Massachusetts[edit]

African Meeting House, Boston, MA - African Meeting House, Boston

- Black Heritage Trail, Boston

- Boston African American National Historic Site, Boston

- Charles Street African Methodist Episcopal Church, Boston

- John Coburn House, Boston

- William C. Nell House, Boston

- John J. Smith House, Boston

- Maria Baldwin House, Cambridge

- Howe House, Cambridge

- William Monroe Trotter House, Dorchester

- William E.B. Du Bois Boyhood Homesite, Great Barrington

- Camp Atwater, North Brookfield

- Paul Cuffe Farm, Westport

- Liberty Farm, Worcester

Michigan[edit]

Detroit Wall, Detroit, MI - Breitmeyer-Tobin Building, Detroit

- Dunbar Hospital, Detroit

- Sacred Heart Roman Catholic Church, Covent, and Rectory, Detroit

- Second Baptist Church of Detroit, Detroit

- Ossian H. Sweet House, Detroit

- The Rainbow Inn, Petoskey

- Brewster-Wheeler Recreation Center, Detroit

- Sidney D. Miller Middle School, Detroit

- Detroit Wall, Detroit

- Nacirema Club, Detroit

- New Bethel Baptist Church, Detroit

- Underground Railroad Living Museum, Detroit

- Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History, Detroit

- Black Bottom, Detroit

Minnesota[edit]

Harriet Island Pavilion, St. Paul, MN - Casiville Bullard House, St. Paul

- Edward S. Hall House, St. Paul

- Harriet Island Pavilion, St. Paul

- Highland Park Tower, St. Paul

- Holman Field Administration Building, St. Paul

- Lena O. Smith House, Minneapolis

- Pilgrim Baptist Church, St. Paul

- St. Mark's African Methodist Episcopal Church, Duluth

Mississippi[edit]

Missouri[edit]

Montana[edit]

- Fort Missoula Historic District, Missoula

Nebraska[edit]

- Jewell Building, Omaha

- Malcolm X House Site, Omaha

- Webster Telephone Exchange Building, Omaha

Nevada[edit]

- Moulin Rouge Hotel, Las Vegas

New Hampshire[edit]

- Portsmouth African Burying Ground, Portsmouth

New Jersey[edit]

Shadow Lawn, West Long Branch, NJ - Bethany Baptist Church, Newark

- Bordentown School

- Fisk Chapel, Fair Haven

- Gethsemane Cemetery, Little Ferry

- Grant AME Church, Chesilhurst

- Perth Amboy City Hall

- Roosevelt Stadium

- Shadow Lawn, West Long Branch

- State Street Public School, Newark

- William R. Allen School, Burlington

New Mexico[edit]

- Hawikuh, Zuni

New York[edit]

- 369th Regiment Armory, Manhattan

- African Burial Ground National Monument, Manhattan

- A.M.E. Zion Church of Kingston and Mount Zion Cemetery, Kingston

- Apollo Theater, Manhattan

- Beecher-McFadden Estate, Peekskill

- Bethel AME Church and Manse, Huntington

- Claude McKay Residence, Manhattan

- Dunbar Apartments, Manhattan

- Durham Memorial A.M.E. Zion Church, Buffalo

- Edward Kennedy "Duke" Ellington House, Manhattan

- Elmendorf Reformed Church, Manhattan, and its newly discovered burial ground at 126th St and Second Avenue

- Florence Mills House, Manhattan

- Foster Memorial AME Zion Church, Tarrytown

- Harlem African Burial Ground, New York

- Harlem River Houses, Manhattan

- Harriet Tubman Home for the Aged, Auburn

- Houses on Hunterfly Road District, Brooklyn

- Jack Peterson Memorial, Croton-on-Hudson

- James Weldon Johnson House, Manhattan

- Jay Estate, Rye

- John Brown Farm, Lake Placid

- John Roosevelt "Jackie" Robinson House, Queens

- Langston Hughes House, Manhattan

- Lemuel Haynes House, New South Granville

- Louis Armstrong House, Queens

- Macedonia Baptist Church, Buffalo

- Matthew Henson Residence, Manhattan

- Minton's Playhouse, Manhattan

- Monument to First Rhode Island Regiment, Yorktown Heights

- Newburgh Colored Burial Ground, Newburgh

- New York Amsterdam News Building, Manhattan

- Paul Robeson Home, Manhattan

- Ralph Bunche House, Queens

- Rapp Road Community Historic District, Albany

- Rye African-American Cemetery, Rye

- Saint Paul's Church National Historic Site, Mount Vernon

- Sandy Ground Historic Archeological District, Staten Island

- Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Manhattan

- Skinny House (Mamaroneck, New York), Mamaroneck

- St. Benedict the Moor Church, Manhattan

- St David African Methodist Episcopal Zion Cemetery, Sag Harbor

- St. George's Episcopal Church, New York

- St. James AME Church, Ithaca

- St. Nicholas Historic District, Manhattan

- St. Philip's Episcopal Church, Manhattan

- Stony Hill Cemetery, Harrison

- Sylvester Manor, Shelter Island

- Valley Road Historic District, Manhasset

- Villa Lewaro, Irvington

- Will Marion Cook House, Manhattan

- Waddington Historic Distinct, Waddington

North Carolina[edit]

Ohio[edit]

- Mount Zion Baptist Church, Athens

- Jacob Goldsmith House, Cleveland

- Lincoln Theatre, Columbus

- South School, Yellow Springs

- Colonel Charles Young House, Wilberforce

- William C. Johnston House and General Store, Burlington

- Macedonia Church, Burlington

- John Mercer Langston House, Oberlin

- African Jackson Cemetery, Piqua

- Classic Theater, Dayton

- Dunbar Historic District, Dayton

- Women's Christian Association, Dayton

- St. Andrew's Episcopal Church, Cleveland

- St. Augustine's Episcopal Church, Youngstown

- St. Andrew's Episcopal Church, Cincinnati

Oklahoma[edit]

- A. J. Mason Building, Tullahassee

- Black Theater of Ardmore, Ardmore

- Boley Historic District, Boley

- C.L. Cooper Building, Eufaula

Straight University, New Orleans, graduating class of 1901 - Douglass High School Auditorium, Ardmore

- Dunbar School, Ardmore

- Eastside Baptist Church, Okmulgee

- First Baptist Central Church, Okmulgee

- First Baptist Church, Muskogee

- Gower Cemetery, Edmond

- J. Cody Johnson Building, Wewoka

- Johnson Hotel and Boarding House, Duncan

- Manual Training High School for Negroes, Muskogee

- Melvin F. Luster House, Oklahoma City

- Mill-Washington School, Red Bird

- Miller Brothers 101 Ranch, Ponca City

- Okmulgee Colored Hospital, Okmulgee

- Okmulgee Downtown Historic District, Okmulgee

- Red Bird City Hall, Redbird

- Rock Front, Vernon

- Rosenwald Hall, Lima

- Taft City Hall, Taft

- Ward Chapel AME Church, Muskogee

Pennsylvania[edit]

- Adelphi School, Philadelphia

- Asbury AME Church, Chester

- Bethel AME Church, Reading

- Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church of Monongahela City, Monongahela City

- Calvary Baptist Church, Chester

- Camptown Historic District, LaMott

- Cheyney University of Pennsylvania, Cheyney

- Clement Atkinson Memorial Hospital, Coatesville

- Crozer Theological Seminary, Upland

- Eden Cemetery, Collingdale

- Ercildoun Historic District in Chester County

- Frances Ellen Watkins Harper House, Philadelphia

- Hamorton Historic District, Kennett Square

- Henry O. Tanner House, Philadelphia

- Institute for Colored Youth, Philadelphia

- John Brown House, Chambersburg

- Lebanon Cemetery, Philadelphia

- Little Jerusalem AME Church, Cornwells Heights

- Melrose, Cheyney

- Mother Bethel AME Church, Philadelphia

- Mount Gilead AME Church, Buckingham Township

- Oakdale, Chadds Ford

- Slate Hill Cemetery, Morrisville

- Thompson Cottage, Concord Township

- Union Methodist Episcopal Church, Philadelphia

- Wesley AME Zion Church, Philadelphia

- White Hall of Bristol College, Croyden

- White Horse Farm, Phoenixville

Puerto Rico[edit]

- Hacienda Azucarera La Esperanza, Manati

Rhode Island[edit]

Hard Scrabble, Providence, RI - Cato Hill Historic District, Woonsocket

- Hard Scrabble, Providence

- Shiloh Baptist Church, Newport

- Smithville Seminary, Scituate

South Carolina[edit]

- Hampton-Pinckney Historic District, Greenville

- Paris Simkins House, Edgefield

- Dr. Cyril O. Spann Medical Office, Columbia

Tennessee[edit]

- Orange Mound, Memphis, Memphis

- Toussaint L'Ouverture County Cemetery, Franklin

Texas[edit]

Utah[edit]

- Trinity AME Church, Salt Lake City

Vermont[edit]

- Old Stone House Museum, Brownington

Virginia[edit]

- Belmont – Virginia

- Woodland Cemetery (Richmond, Virginia)

- Shockoe Bottom African Burial Ground (Richmond, Virginia)

- Shockoe Hill African Burying Ground (Richmond, Virginia)

- First African Baptist Church (Richmond, Virginia)

- Lumpkin's Jail (Richmond, Virginia)

- Maggie L. Walker National Historic Site (Richmond, Virginia)

- Jackson Ward (Richmond, Virginia)

- Sixth Mount Zion Baptist Church (Richmond, Virginia)

- St. Luke Building (Richmond, Virginia)

- Hippodrome Theater (Richmond, Virginia)

- Virginia Union University (Richmond, Virginia)

- Fourth Baptist Church Richmond, Virginia)

- Ebenezer Baptist Church (Richmond, Virginia)

Virgin Islands[edit]

- Christiansted Historic District, Christiansted

- Christiansted National Historic Site, Christiansted

- Emmaus Moravian Church and Manse, Coral Bay

- Estate Carolina Sugar Plantation, Coral Bay

- Estate Neltjeberg, Charlotte Amalie

- Estate Niesky, Charlotte Amalie

- Fort Christian, Charlotte Amalie

- Friedensthal Mission, Christiansted

- New Herrnhut Moravian Church, Charlotte Amalie

Washington[edit]

West Virginia[edit]

- African Zion Baptist Church, Malden

- Barnett Hospital and Nursing School, Huntington

- Bethel AME Church, Parkersburg

- Booker T. Washington High School, London

- Camp Washington-Carver Complex, Clifftop

- Canty House, Institute

- Douglass Junior and Senior High School, Huntington

- East Hall, Institute

- Elizabeth Harden Gilmore House, Charleston

- Garnet High School, Charleston

- Halltown Colored Free School, Halltown

- Halltown Union Colored Sunday School, Halltown

- Hancock House, Bluefield

- Henry Logan Memorial AME Church, Parkersburg

- Harpers Ferry National Historical Park, Harpers Ferry

- Storer College, Harpers Ferry

- Hill Top House Hotel, Harpers Ferry

- Jefferson County Courthouse, Charles Town

- Kelly Miller High School, Clarksburg

- Maple Street Historic District, Lewisburg

- Mattie V. Lee Home, Charleston

- Mount Pisgah Benevolence Cemetery, Romney

- Mt. Pleasant School, Gerrardstown

- Mt. Tabor Baptist Church, Lewisburg

- Samuel Starks House, Charleston

- Second Ward Negro Elementary School, Morgantown

- Simpson Memorial United Methodist Church, Charleston

- Trinity Memorial Methodist Episcopal Church, Clarksburg

- Union Historic District, Union

- Washington Place, Romney

- West Virginia Colored Children's Home, Huntington

- Weston Colored School, Weston

- World War Memorial, Kimball

Wisconsin[edit]

- East Dayton Street Historic District, Madison

See also[edit]

- African-American Heritage Sites

- List of museums focused on African Americans

- List of streets named after Martin Luther King, Jr.

References[edit]

- ^ a b Casey Cep (January 27, 2020). "The Fight to Preserve African American History". The New Yorker. Retrieved February 10, 2022.

- ^ a b National Register of Historic Places: African American Historic Places; National Park Service & National Trust for Historic Preservation; The Preservation Press; Washington D.C.; 1994

- ^ Teaching with Historic Places Archived May 27, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s The Negro Pilgrimage in America: C. Eric Lincoln; Bantam Books, New York; 1967

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Before the Mayflower: A History of the Negro in American 1619-1964; Lerone Bennett, Jr.; Pelican Books; Baltimore, Maryland; 1964

- ^ "H.R.1179 - African-American Burial Grounds Network Act". Congress.Gov. February 13, 2019. Retrieved December 26, 2021.

Further reading[edit]

- Ballard, Allan; One More Day's Journey: The Story of a Family and a People; New York; McGraw-Hill, 1984

- Durham, Philip, and Everettt L. Jones; The Adventures of the Negro Cowboys; New York: Bantam Books, 1969

- Ferguson, Leland G.; Uncommon Ground: Archeology and Colonial African America; Washington, D.C.; Smithsonian Institution Press, 1992

- Harley, Sharon, and Rosalyn Terborg-Penn; The Afro-American Woman: Struggles and Images; Port Washington; Kennikat Press; 1978

- Higgans, Nathan I.; Harlem Renaissance; New York; Oxford University Press; 1971

- Lyon, Elizabeth A.; Cultural and Ethnic Diversity in Historic Preservation. Information Series, no. 65; Washington D.C.; National Trust for Historic Preservation, 1992.

- McFeely, William S.; Frederick Douglass; New York; Norton, 1990.

- National Register of Historic Places: African American Historic Places; National Park Service & National Trust for Historic Preservation; The Preservation Press; Washington D.C.; 1994

- Painter, Nell Irvin; Exodusters: Black Migration to Kansas after Reconstruction; New York; Norton; 1976

- Reynolds, Gary A. and beryl Wright; Against the Odds: African American Artists and the Harmon Foundation. Newark, New Jersey; The Newark Museum, 1989