New Zealand and the United Nations

| |

| United Nations membership | |

|---|---|

| Membership | Full member |

| Since | 26 June 1945 |

| UNSC seat | Non-permanent |

| Permanent Representative | Carolyn Schwalger[1] |

|

|---|

|

|

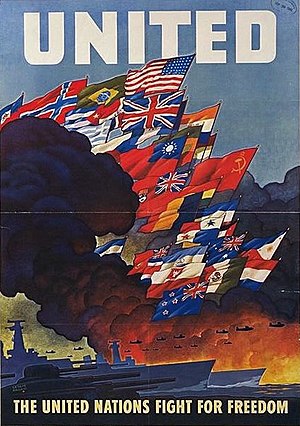

New Zealand is a founding member of the United Nations, having taken part in the 1945 United Nations Conference on International Organization in San Francisco.

Since its formation, New Zealand has been actively engaged in the organisation. New Zealand sees the UN as a means of collective security, mainly in the South Pacific region, particularly because New Zealand is a relatively small nation and has very little control over much larger countries or significant events. The UN was also seen as a way of safe-guarding New Zealand, a somewhat fledgling country at the time. The successor New Zealand governments also felt that the United Nations was an important political and military ally to have as it was an integral part of New Zealand's "Collective Security".[2]

New Zealand represents itself and the other constituent countries of the Realm of New Zealand (Niue and the Cook Islands) in the United Nations. The Cook Islands and Niue have full treaty-making capabilities recognized by United Nations Secretariat in 1992 and 1994 respectively[3][4] and have the option of seeking membership in the United Nations. The Cook Islands and Niue are both associated states of the Realm and members of specialized agencies of the UN such as WHO[5] and UNESCO.[6] They have since become parties to a number of international treaties which the UN Secretariat acts as a depositary for, such as the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change[7] and the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea,[8] and are treated as non-member states.[9][3] Both the Cook Islands and Niue have expressed a desire to become a UN member state, but New Zealand has said that they would not support the application without a change in their constitutional relationship, in particular their right to New Zealand citizenship.[10][11]

Former Prime Minister Helen Clark headed the United Nations Development Programme from 2009 to 2017, in which role she was the most senior New Zealander in the UN bureaucracy. In 2016, she stood for the position of Secretary-General of the United Nations, but was unsuccessful.[12][13]

History[edit]

New Zealand's membership of the United Nations as a founder was a considerable change in foreign policy, although strongly supported by the First Labour Government which in 1935 had a firm belief in the concept of collective security through the League of Nations.[14] Previous governments had put all their political and military reliance in the "Mother Country" (the United Kingdom), and expressed reservations about particular policies privately.

During the Second World War, New Zealand realized that it could no longer rely on Britain for protection. After the Royal Navy's defeat in the Pacific, New Zealand began searching for a way to increase security of its waters and people through mainly collective security arrangements. Following the war, Prime Minister Peter Fraser became actively involved in the creation of the United Nations. He believed that an organization such as the UN could be a place to solve international problems peacefully, ensure New Zealand a say in world affairs, protect the interests of small powers and ally with major world powers like the United States (later reinforced through the ANZUS security agreement). Although on some issues Peter Fraser disagreed with fellow founding members over,[clarification needed] especially on the creation of the United Nations Security Council, he was against giving major countries veto power, because it allowed one power to stop any action and would exclude smaller powers from having a say in world issues. He feared that the US, USSR, UK and France (China not being a major power of the time) would not accept equal status with smaller countries. Fraser was later quoted on the issue: "It is very bad if one nation can hold up the advancement of mankind".[15]

United Nations Security Council[edit]

New Zealand (and Norway) declined nomination to the Security Council in 1946, refusing nomination by the Ukrainian SSR. New Zealand had proposed Australia as the "obvious choice" for a South Pacific region representative.

New Zealand served on the United Nations Security Council as a non-permanent member for the Western European and Others Group in 1954–55, 1966[16] and 1993–94. It secured a seat again in 2015–16 after the election in 2014.[17][18]

Support for UN military actions[edit]

Right from the start, Peter Fraser supported the formation of Israel. Successive governments have provided military support in the Middle East, Kashmir, India/Pakistan, Cyprus, Cambodia and Korea. More recently, New Zealand peace-keeping troops have been sent to East Timor, Iraq and Afghanistan.

Korean War[edit]

New Zealand was among the first nations to respond to the United Nations call for help. New Zealand joined 15 other nations including the United Kingdom and the United States in the anti-communist war. But the Korean War was also significant, as it marked New Zealand's first move towards association with the United States and United Nations in supporting that country's stand against communism.

New Zealand contributed six frigates, several smaller craft and a 1044 strong volunteer force (known as K-FORCE) to the Korean War. The ships were under the command of a British flag officer and formed part of the U.S. Navy screening force during the Battle of Inchon, performing shore raids and inland bombardment. New Zealand troops remained in Korea in significant numbers for four years after the 1951 armistice, although the last New Zealand soldiers did not leave until 1957 and a single liaison officer remained until 1971. A total of 3,794 New Zealand soldiers served in K-FORCE and 1300 in the Navy deployment. 33 were killed in action, 79 wounded and one soldier was taken prisoner. That prisoner was held in North Korea for eighteen months and repatriated after the armistices. This showed the United Nations that New Zealand was committed to the organization and was willing to support the UN if required.

Kashmir conflict[edit]

In 1952, three New Zealand officers were seconded as military observers for the United Nations Military Observer Group in the Kashmir, to supervise a ceasefire between India and Pakistan. New Zealand observers saw service with the force until 1976.[19]

East Timor[edit]

Following East Timor's vote for independence in 1999, the United Nations INTERFET (International Force for East Timor) was dispatched into the area. INTERFET was made up of contributions from 17 nations, about 9,900 in total. At its peak, the New Zealand Defence Force had 1,100 personnel in East Timor - New Zealand's largest overseas military deployment since the Korean War. Overall New Zealand's contribution saw just short of 4,000 New Zealanders serve in East Timor. In addition to their operations against militia, the New Zealand troops were also involved in construction of roads and schools, water supplies and other infrastructural assistance. English lessons and medical aid were also provided.

Iraq War[edit]

The New Zealand government opposed and officially condemned the 2003 invasion of Iraq by the US-led "Coalition of the Willing" and did not contribute any combat forces. However, in accordance with United Nations Security Council Resolution 1483 New Zealand contributed a small engineering and support force to assist in post-war reconstruction and provision of humanitarian aid. The engineers returned home in October, 2004 and New Zealand is still represented in Iraq by liaison and staff officers working with coalition forces.

Support for UN Aid Programmes[edit]

New Zealand supported aid programmes through UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation) and UNICEF (United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund). In 1947, New Zealand joined ECAFE (Economic Commission for Asia and the Far East), a UNO regional commission from Iran to Japan, which tries to promote Economic development. Promoting economic development was seen as a way of maintaining global peace because it believed that poverty and unemployment was a main factor in social unrest that could lead to uprise or war.

United Nations Humans Rights Council[edit]

New Zealand was unsuccessful[20] in its bid for election in 2009 to the 47-seat United Nations Human Rights Council for the term 2009-2012 even though New Zealand was the first country from the Pacific region to stand. New Zealand's bid for election was initially supported by Canada and Australia, who are its partners under the 'CANZ' agreement.[21] New Zealand has a long history of legislation that advances human rights, such as being the first country to give women the right to vote.[22]

Internationally, New Zealand works closely with Pacific Island partners to support and assist the promotion and protection of human rights to influence positive and real change that makes lasting differences in people's lives. In May 2008, New Zealand's work to improve the rights of people with disabilities both domestically and internationally was recognised through the Franklin Delano Roosevelt International Disability Award.

Diplomatic representation[edit]

New Zealand currently has a permanent diplomatic mission to the UN in New York City and also has Permanent Missions to the United Nations Offices in Geneva and Vienna, which focus on human rights and disarmament issues respectively. Mission staff is engaged in multilateral diplomacy with many different countries and organizations. Representatives from the Missions communicate New Zealand's policy positions to UN officials and foreign delegates, and to convey their views back to Ministry representatives in Wellington and New Zealand's overseas posts. The Missions also promote New Zealand's positions in negotiations on UN resolutions, reports and activities.

New Zealand's contribution to the budget for 2008 was 0.256% of the total United Nations budget totalling NZD$7.3m. New Zealand provided NZD$1.2m in 2008 to financing of the Capital Master Plan for the phased renovation of the UN Headquarters. New Zealand also paid further instalments each year until 2011. In the 2006/07 New Zealand financial year, it contributed NZD$16.9m to 14 UN Peacekeeping operations around the world. New Zealand also contributed NZD$986,000 in 2008 to the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda and the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia.[23][24]

Several New Zealanders currently serve on the following United Nations bodies:

- Sir Kenneth Keith is a judge of the International Court of Justice

- Mr Paul Hunt is the Special Rapporteur on the right to health

- Mr Laurence Zwimpfer currently chairs the UNESCO Information For All Programme

New Zealand is currently represented on the following United Nations bodies:

- United Nations Security Council (2015–16)

- World Food Programme Executive Board

- UNEDCO (Economic and Social Council)

- Joint United Nations Programme for HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) Programme Coordinating Board

See also[edit]

- Foreign relations of New Zealand

- United Nations Transitional Administration in East Timor

- 2006 East Timorese crisis

- List of permanent representatives of New Zealand to the United Nations in Geneva

- List of permanent representatives of New Zealand to the United Nations in Vienna

- List of permanent delegates of New Zealand to UNESCO

References[edit]

- ^ "New Permanent Representative of New Zealand Presents Credentials".

- ^ Bowen, George; Agent, Roydon; Warburton, Graham (2007) [2007]. "8". Year 11 History. North Shore, Auckland, New Zealand: Pearson Education New Zealand. pp. 142–143. ISBN 978-0-7339-9280-3.

- ^ a b "Organs Supplement", Repertory of Practice (PDF), UN, p. 10

- ^ The World today, UN

- ^ "Countries". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 21 August 2004.

- ^ "Member States". United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Archived from the original on 8 July 2012.

- ^ "Parties to the Convention and Observer States". United Nations. Archived from the original on 5 July 2013.

- ^ "Chronological lists of ratifications of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea". United Nations.

- ^ "The World Today" (PDF). United Nations.

- ^ "NZ PM rules out discussion on Cooks UN membership". Radio New Zealand. 19 June 2015. Retrieved 16 April 2016.

- ^ "Niue to seek UN membership". Radio New Zealand. 27 October 2016. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- ^ Pilkington, Ed (4 April 2016). "Helen Clark, former New Zealand PM, enters race for UN secretary general". Retrieved 5 April 2016.

- ^ Hunt, Elle (14 June 2017). "Helen Clark: I hit my first glass ceiling at the UN". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- ^ McGibbon, I.C. (1981) Blue-Water Rationale:The Naval Defence of New Zealand 1914-1942, page 256 (GP Print, Wellington, NZ) ISBN 0-477-01072-5

- ^ David Hackett Fischer (2012). Fairness and Freedom: A History of Two Open Societies: New Zealand and the United States. Oxford University Press. p. 354.

- ^ Bowen, George (2001) [1997]. "4". Defending New Zealand. Auckland, New Zealand: Addison Wesley Longman. p. 12. ISBN 0-582-73940-3.

- ^ "New Zealand lands seat on UN Security Council". Stuff. 17 October 2014. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- ^ "New Zealand UN Security Council Candidate 2015-16". New Zealand Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade. Retrieved 3 January 2012.

New Zealand is seeking a non-permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council in 2015-16. Elections are in 2014.

- ^ "Peacekeeping Operations in Pakistan". Torpedo Bay Navy Museum. Retrieved 28 October 2021.

- ^ United States Elected to Human Rights Council for First Time, with Belgium, Hungary, Kyrgyzstan, Norway, as 18 Seats Filled In Single Round of Voting

- ^ NZ Candidature for Human Rights Council 2009 – 2012 – Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade

- ^ NZ seeks UN Human Rights Council seat – New Zealand Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade

- ^ United Nations - NZ's engagement with the UN - NZ Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade - Inside Page

- ^ United Nations - NZ's contribution - NZ Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade

External links[edit]

- "New Zealand and the United Nations", historical overview on a New Zealand government website

- UNA NZ Official Website