Saul Alinsky

Saul Alinsky | |

|---|---|

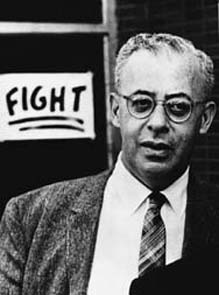

Alinsky in 1963 | |

| Born | Saul David Alinsky January 30, 1909 Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Died | June 12, 1972 (aged 63) |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | University of Chicago (PhB) |

| Occupation(s) | Community organizer, writer, political activist |

| Years active | 1960s |

| Notable work | Rules for Radicals (1971) |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 2 |

| Awards | Pacem in Terris Award, 1969 |

| Signature | |

| |

| Notes | |

Saul David Alinsky (January 30, 1909 – June 12, 1972) was an American community activist and political theorist. His work through the Chicago-based Industrial Areas Foundation helping poor communities organize to press demands upon landlords, politicians, bankers and business leaders won him national recognition and notoriety. Responding to the impatience of a New Left generation of activists in the 1960s, Alinsky – in his widely cited Rules for Radicals: A Pragmatic Primer (1971) – defended the arts both of confrontation and of compromise involved in community organizing as keys to the struggle for social justice.

Beginning in the 1990s, Alinsky's reputation was revived by commentators on the political right as a source of tactical inspiration for the Republican Tea Party movement and subsequently, by virtue of indirect associations with both Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama, as the alleged source of a radical Democratic political agenda. While criticized on the political left for an aversion to broad ideological goals, Alinsky has also been identified as an inspiration for the Occupy movement and campaigns for climate action.

Early life[edit]

Childhood[edit]

Saul Alinsky was born in 1909 in Chicago, Illinois, to Russian Jewish immigrant parents, the only surviving son of Benjamin Alinsky's marriage to his second wife, Sarah Tannenbaum Alinsky.[5] His father started out as a tailor, then ran a delicatessen and a cleaning shop.

Both parents were strict Orthodox. Alinsky describes himself as being devout until the age of 12, the point at which he began to fear his parents would force him to become a rabbi. Although he had "not personally" encountered "much antisemitism as a child", Alinsky recalled that "it was so pervasive . . . you just accepted it as a fact of life." Called up for retaliating against some Polish boys, Alinsky acknowledged one rabbinical lesson that "sank home." "It's the American way . . . Old Testament . . . They beat us up, so we beat the hell out of them. That's what everybody does." The rabbi looked at him for a moment and said quietly, "You think you're a man because you do what everybody does. But I want to tell you something great: 'where there are no men, be thou a man'". Alinsky considered himself an agnostic,[6][7][8] but when asked about his religion would "always say Jewish."[9]

College studies[edit]

In 1926, Alinsky entered the University of Chicago. He studied in America's first sociology department under Ernest Burgess and Robert E. Park. Overturning the propositions of a still ascendant eugenics movement, Burgess and Park argued that social disorganization, not heredity, was the cause of disease, crime and other characteristics of slum life. As the passage of successive waves of immigrants through such districts had demonstrated, it is the slum area itself, and not the particular group living there, with which social pathologies were associated.[10] Yet Alinsky claimed to be unimpressed: what "the sociologists were handing out about poverty and slums"—"playing down the suffering and deprivation, glossing over the misery"—was "horse manure."[9]

The Great Depression put an end to an interest in archaeology: after the stock-market crash "all the guys who funded the field trips were being scraped off Wall Street sidewalks." A chance graduate fellowship moved Alinsky on to criminology. For two years, as a "nonparticipant observer", he claims to have hung out with Chicago's Al Capone mob (he explains that, as they "owned the city", they felt they had little to hide from a "college kid"). Among other things about the exercise of power, he says they taught him was "the terrific importance of personal relationships".[11] Alinsky took a job with the Illinois State Division of Criminology, working with juvenile delinquents and at the Joliet State Penitentiary. He recalls it as a dispiriting experience: if he dwelt on the contributing causes of crime, such as poor housing, racial discrimination or unemployment, he was labelled a "Red."[12]

Organizing[edit]

The Back of the Yards Neighborhood Council[edit]

In 1938, Alinsky gave up his last employment at the Institute for Juvenile Research, University of Illinois at Chicago, to devote himself full-time as a political activist. In his free time he had been raising funds for the International Brigade (organized by the Communist International) in the Spanish Civil War and for Southern Sharecroppers, organizing for the Newspaper Guild and other fledgling unions, fighting evictions and agitating for public housing.[11] He also began to work alongside the CIO (Congress of Industrial Organizations) and its president John L. Lewis. (In an "un-authorized biography" of the labor leader Alinsky wrote that he later mediated between Lewis and President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the White House).[13]

Alinsky's idea was to apply the organizing skills he believed he had mastered "to the worst slums and ghettos, so that the most oppressed and exploited elements could take control of their own communities and their own destinies. Up until then, specific factories and industries had been organized for social change, but never whole communities."[14]

In the belief that if he could trial his approach in these neighborhoods, he could do so successfully anywhere, Alinsky looked to the back of the Chicago Stockyards (the area made infamous by Upton Sinclair's 1905 novel The Jungle). There with Joseph Meegan, a park supervisor, Alinsky set up the Back of the Yards Neighborhood Council (BYNC). Working with the archdiocese, the Council succeeded in rallying a mix of otherwise mutually hostile Catholic ethnics (Irish, Poles, Lithuanians, Mexicans, Croats . . .) as well as African Americans to demand, and win, concessions from local meatpackers (in January 1946 the BYNC threw its support behind the first major walkout of the United Packinghouse Workers),[15] landlords and city hall. This, and other efforts in the city's South Side to "turn scattered, voiceless discontent into a united protest" earned an accolade from Illinois governor Adlai Stevenson: Alinsky's aims "most faithfully reflect our ideals of brotherhood, tolerance, charity and dignity of the individual."[16]

In founding the BYNC, Alinsky and Meegan sought to break a pattern of outside direction established by their predecessors in poor urban areas, most notably the settlement houses. The BYNC would be based on local democracy: "organizers would facilitate, but local people had to lead and participate." Residents had to "control their own destiny" and in doing so not only gain new resources but new confidence as well.[17] "Some of Saul's real genius," according to one observer, was "his sense of timing and understanding how others would perceive something. Saul knew that if I grab you by the shoulders and say do this, do that and the other, you're going to resent it. If you make the discovery yourself, you're going to strut because you made it".[18]

The Industrial Areas Foundation[edit]

In 1940, with the support of Roman Catholic Bishop Bernard James Sheil and Chicago Sun-Times publisher and department-store owner Marshall Field, Alinsky founded the Industrial Areas Foundation (IAF), a national community organizing network. The mandate was to partner with religious congregations and civic organizations to build "broad-based organizations" that could train up local leadership and promote trust across community divides.[19] For Alinsky there was also a broader mission.

In what sixty years later, with publication of Robert Putnam's Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community,[20] would have been understood as a concern for the loss of "social capital" (of the organized opportunities for conviviality and deliberation that allow and encourage ordinary people to engage in democratic process), in his own statement of purpose for the IAF, Alinsky wrote:

In our modern urban civilization, multitudes of our people have been condemned to urban anonymity—to living the kind of life where many of them neither know nor care for their neighbors. This course of urban anonymity...is one of eroding destruction to the foundations of democracy. For although we profess that we are citizens of a democracy, and although we may vote once every four years, millions of our people feel deep down in their heart of hearts that there is no place for them—that they do not 'count'.[21]

Through the IAF, Alinsky spent the next 10 years repeating his organizational work--"rubbing raw", as the New York Times saw it "the sores of discontent"[22] and compelling action through agitation--"from Kansas City and Detroit to the farm-worker barrios of Southern California.".[23] Although Alinsky always had rationalizations, his biographer Sanford Horwitt records that "on rare occasions" Alinsky would concede that not all of his mentored projects were "unequivocal successes". There was uncertainty about "what was supposed to happen after the first two or three years, when the original organizer and/or fund-raiser left the community council on its own." Recognizing that the IAF could not be "a holding for People's Organizations", Alinsky thought that one solution would be for community-councils, under their native leadership, to constitute their own inter-city fund-raising and mutual-assistance network. In the early 1950s, Alinsky was talking about "a million-dollar budget to carry us over a three-year plan of organization through the country." The usual corporate and foundation funders proved decidedly cold to the idea.[24]

Successes could also be problematic. In Chicago, the Back of the Yards Council set itself against housing integration and offered no objection to a pattern of "urban renewal" with which Alinsky professed himself "fed-up": "the moving of low-income and, almost without exception, Negro groups and dumping them into other slums," in order to build houses for middle-income whites. There being "no substitute for organized power," in 1959, Alinsky concluded that what the city needed was a powerful black community organization that could "bargain collectively" with other organized groups and agencies, private and public.[25]

Mentoring in The Woodlawn Organization[edit]

With the groundwork prepared by his deputy Edward T. Chambers, Alinsky began mentoring The Woodlawn Organization (TWO), based in the Woodlawn community area on Chicago's South Side. Like other IAF organizations, TWO was a coalition of existing community entities, local block clubs, churches and businesses. These groups paid dues, and the organization was run by an elected board. The TWO moved quickly to establish itself as the "voice" of the black neighborhood, mobilizing, developing and bringing up new leadership. An example was Arthur M. Brazier, the first spokesperson and eventual president of the organization. Starting out as a mail carrier, Brazier became a preacher in a store front church, and then, through TWO, emerged as a national spokesman for the Black Power movement.[26]

In 1961, to show City Hall that TWO was a force to be reckoned with Alinsky combined "two elements—votes, which were the coin of the realm in Chicago politics, and fear of the black mass"—by bussing 2,500 black resident citizens, down to City Hall to register to vote. No administrator in Chicago is said ever to have forgotten that image.[27][full citation needed]

Through TWO, Woodlawn residents challenged the redevelopment plans of the University of Chicago. Alinsky claimed the organization was the first community group not only to plan its own urban renewal but, even more important, to control the letting of contracts to building contractors. Alinsky found it "touching to see how competing contractors suddenly discovered the principles of brotherhood and racial equality." Similar "conversions" were secured from employers elsewhere in the city with mass shop-ins at department stores, tying up bank lines with people exchanging pennies for bills and vice versa, and the threat of a "piss-in" at Chicago O'Hare International Airport.[28]

For Alinsky the "essence of successful tactics" was "originality." When Mayor Daley dragged his heels on building violations and health procedures, TWO threatened to unload a thousand live rats on the steps of city hall: "sort of share-the-rats program, a form of integration":

Any tactic that drags on too long becomes a drag itself. No matter how burning the injustice and how militant your supporters, people get turned off by repetitious and conventional tactics. Your opposition also learns what to expect and how to neutralize you unless you're constantly devising new strategies.

Alinsky said that he "knew the day of sit-ins had ended" when the executive of a military contractor showed him blueprints for the new corporate headquarters. "'And here', the executive said, 'is our sit-in-hall. [You will have] plenty of comfortable chairs, two coffee machines and lots of magazines . . . '". "You are not going to get anywhere", Alinsky concluded, unless you are "constantly inventing new and better tactics" that move beyond your opponent's expectations.[29]

FIGHT, Rochester NY[edit]

In the 1960s, Alinsky focused through the IAF on the training of community organizers. The IAF assisted black community organizing groups in Kansas City and Buffalo, and the Community Service Organization of Mexican Americans in California, training, among others, Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta.

Alinsky's "major battle" followed the 1964 Rochester Race Riot. Alinsky viewed Rochester, New York as a "classic company town"—owned "lock stock and barrel" by Eastman Kodak. Casually exploited by Kodak (whose only contribution to race relations, Alinsky quipped, was "the invention of color film")[30] and by other local businesses, most African Americans held low-pay and low-skill jobs and lived in substandard housing. In the wake of the riots the Rochester Area Churches, together with black civil rights leaders invited Alinsky and the IAF to help the community organize. With the Reverend Franklin Florence, who had been close to Malcolm X, they established FIGHT (Freedom, Integration, God, Honor, Today) to bring community pressure on Kodak to open up employment and city governance.

Concluding that picketing and boycotts would not work, FIGHT began to think of some "far-out tactics along the lines of our O'Hare shit in." This included a "fart-in" at the Rochester Philharmonic, Kodak's "cultural jewel." It was a proposal Alinsky considered "absurd rather than juvenile. But isn't much of life kind of a theater of the absurd?" No tactic that might work was "frivolous." In the end, and following a disruption of its annual stockholders' convention, assisted by Unitarians and others assigning FIGHT their proxies (Alinsky had called on them to "put your stock where your sermons are"), Kodak recognized FIGHT as a broad-based community organization and committed, through a recruitment and training program, to black employment.[31][32]

Rochester was to be the last African American community that Alinsky would help organize through his own intervention.

Community action in the federal War on Poverty[edit]

While in Rochester, Alinsky had been employed four-days a month at the federally-funded Community Action Training Center at Syracuse University.[33][page needed] The 1964 Economic Opportunity Act, passed as a part of Lyndon B. Johnson’s War on Poverty, committed the federal government to promoting the "maximum feasible participation" of targeted communities in the design and delivery of anti-poverty programs.[34]

This appeared to acknowledge what Alinsky insisted was the key to social and economic deprivation, "political poverty":

Poverty means not only lacking money, but also lacking power. ... When ... poverty and the lack of power bar you from equal protection, equal equity in the courts, and equal participation in the economic and social life of your society, then you are poor. ... [An] anti-poverty program must recognise that its program has to do something about not only economic poverty but also political poverty[35]

Alinsky was sceptical of Community Action Program (CAP) funding under the Act doing more than provide relief for the "welfare industry": "the use of poverty funds to absorb staff salaries and operating costs by changing the title of programs and putting a new poverty label here and there is an old device". If it was to achieve more than this, there had to be meaningful representation of the poor "through their own organised power".[35]

In practice this would mean that the federal sponsor for community action, the Office of Economic Opportunity (OEO), should bypass city halls and either fund existing militant organisations such as FIGHT in Rochester (although these could never allow the federal government to be their core funder) or, in communities not already organized, seek out local leadership to initiate the process of building a resident organization. Amendments to OEO funding in the summer of 1965 ruled out any such "creative federalism". These gave city halls the right to select the official Community Action Agency (CAA) for their community and reserved two-thirds of the CAA boards for business representative and elected officials.[36] There was no prospect of a federal mandate favoring Alinsky's organizing model.

The one-year OEO grant for the program at Syracuse that had hired Alinsky was not renewed.[37] When the program trainees began organizing residents against city agencies, the mayor withdrew cooperation.[38]

Political contentions[edit]

Communism[edit]

Alinsky never became a direct target of McCarthyism. He was never called before a congressional investigating committee nor had to endure a determined press campaign to identify and exclude him as a communist “fellow traveler”. Alinsky liked to think this because of his toughness and the ridicule he would have heaped upon his persecutors. Herb March, the most prominent Communist Party member with the Packinghouse Workers in Chicago, said he would "place a little more emphasis ... on the Church influence", but also allowed that, as the government "undoubtedly must have had him under close surveillance", they cannot have had "anything" on him.[39]

Yet Alinsky was not "untouched by the climate of fear, suspicion and innuendo". Rumors of communist associations and Red-baiting would follow him into the 1960s,[40] and, once his name was associated with leading Democratic-Party presidential contenders, would follow his legacy into the new century. For some of his "anti-communist" critics, Alinsky's definition in Reveille for Radicals of what it is to be a "radical" may have been a sufficient indictment:

The Radical believes that all peoples should have a high standard of food, housing, and health … The Radical places human rights far above property rights. He is for universal, free public education and recognizes this as fundamental to the democratic way of life … The Radical believes completely in real equality of opportunity for all peoples regardless of race, color, or creed. He insists on full employment for economic security but is just as insistent that man's work should not only provide economic security but also be such as to satisfy the creative desires within all men.[41]

Alinsky would not apologize for working with Communists at a time when, in his opinion, they were doing "a hell of a lot of good work in the vanguard of the labor movement and ... in aiding blacks and Okies and Southern sharecroppers."[42] "Anyone", he remarked, "who was involved in the causes of the thirties and says he didn't know any communists is either a liar or an idiot". They were "all over the place, fighting for the New Deal the CIO and so forth".[11]

Alinsky also owned being "sympathetic to Russia at that time [i.e. in the 1930s before the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact] because it was the one country that seemed to be taking a strong position against Hitler... If you were anti-fascist on the international front in those days you had to stand with Communists". But Alinsky insists he "never joined the party" for reasons "partly philosophic":

One of my articles of faith is what Justice Learned Hand called "that ever-gnawing inner doubt as to whether you are right." I've never been sure I'm right but also I'm also sure nobody else has this thing called truth. I hate dogma. People who believed they owned the truth have been responsible for the most terrible things that have happened in our world, whether they were Communist purges or the Spanish Inquisition or the Salem witch hunts.[11]

There seemed to be no sympathy for the centralizing Soviet model. In Reveille Alinsky is "as contemptuous of 'top down' approaches to social planning as he is of laissez-faire economic policies".[43] The Radical, he says, "will bitterly oppose complete Federal control of education. He will fight for individual rights and against centralized power …The Radical is deeply interested in social planning but just as deeply suspicious of and antagonistic to any idea of plans which work from the top down. Democracy to him is working from the bottom up". With Thomas Jefferson, the Radical believes that the people are "the most honest and safe", if not always the wisest, "depository of the public interest."[41]

On the issue of whether communists should be banned from unions and other social organizations, Alinsky argued that:

[The question is] whether there can be developed an American Progressive Movement in which the Communists are forced to follow along or get out on the basis of the issues--a movement so healthy, so filled with the vitality of real American Radicalism, that the Communists will wear their teeth down to their jaws trying to bore from within. I know that the latter can be done

But in the meantime, Alinsky believed that "certain fascist mentalities" posed a far greater threat to the country than "the damn nuisance of Communism".[40]

The Black Power movement[edit]

In the mid-1960s, civil rights activists began to call for "Black Power"—for Stokely Carmichael a "call for black people to define their own goals, to lead their own organizations".[44][45] Alinsky appeared not to be fazed. "I agree with the concept," he said in the fall of 1966. "We've always called it community power, and if the community is black, it's black power." But a year later he was relating, with evident satisfaction, that when he had asked Carmichael at a Detroit meeting to cite one concrete example of what he meant by Black Power, Carmichael had named the FIGHT project in Rochester. Carmichael, Alinsky suggested, should stop "going round yelling 'Black Power!'" and "really go down and organize."[46]

Alinsky had a sharper response to the more strident black nationalism of Maulana Karenga, mistakenly identified in news reports as a board member of the newly formed Interreligious Foundation for Community Organization. In an angry letter to the Foundation's executive director, Lucius Walker, Alinsky took exception to one of Karenga's "insights," that "blacks are a country and if you support America you are against my community." This Alinsky found "repugnant and nauseous." He and his associates would not only "plead guilty to supporting America" but would "gladly admit that we love our country." Horwitt notes that in 1968 "virtually no leftist dissenter – black or white – was using this kind of patriotic rhetoric."[47]

By 1970, Alinsky had conceded publicly that "all whites should get out of the black ghettos. It's a stage we have to go through."[48]

The Student New Left[edit]

At the beginning of the 1960s, in the first postwar generation of college youth Alinsky appeared to win new allies. Disclaiming any "formulas" or "closed theories", Students for a Democratic Society called for a "new left ... committed to deliberativeness, honesty [and] reflection."[49] More than this, the New Left seemed to place community organizing at the heart of their vision.

The SDS insisted that students "look outwards" beyond the campus "to the less exotic but more lasting struggles for justice." "The bridge to political power" would be "built through genuine cooperation, locally, nationally, and internationally, between a new left of young people and an awakening community of allies." To stimulate "this kind of social movement, this kind of vision and program in campus and community across the country",[49] in 1963, the SDS launched (with $5000 from United Automobile Workers) the Economic Research and Action Project (ERAP). SDS community organizers would help draw white neighborhoods into an "interracial movement of the poor". By the end of 1964, ERAP had ten inner-city projects engaging 125 student volunteers.[50]

In the summer of 1964, Ralph Helstein of the Packinghouse Workers, one of the few labor leaders interested in the emergence of the New Left, arranged for Alinsky to meet SDS founders Tom Hayden and Todd Gitlin. To Helstein's dismay Alinsky dismissed Hayden and Gitlin's ideas and work as naive and doomed to failure. The would-be organizers were absurdly romantic in their view of the poor and of what could be achieved by consensus. Horwitt notes that "'Participatory democracy,' the central concept the SDS's Port Huron Statement, meant something fundamentally different . . . to what 'citizen participation' meant to Alinsky." Within community organizations Alinsky "put a premium on strong leadership, structure and centralized decision-making."[51]

When SDS volunteers set up shop, JOIN (Jobs or Income Now), in "Hillbilly Harlem" uptown Chicago, they duly crossed town to meet with Alinsky in Woodlawn. But there was not to be a meeting of minds.[52][full citation needed] The JOINers charged Alinsky with being "stuck in the past", and, perhaps most cutting, to be unwilling to confront white racism. To meet the challenge of growing black dissent following the August 1965 Watts riots, King and his Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) had sought a victory in the North with the Chicago Freedom Movement (CFM). JOIN later claimed that they pushed whites on the race question "at every opportunity" and "even mobilized members to support Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.'s campaign to desegregate housing in Chicago in the summer of 1966".[53][full citation needed]

It is not clear that participation by Alinsky in the Chicago Freedom Movement was either offered or invited. Yet "Freedom Summer" in 1965 seemed to follow the Alinsky playbook: "The job of the organizer is to maneuver and bait the establishment so that it will publicly attack him as a 'dangerous enemy'. The hysterical instant reaction of the establishment [will] not only validate [the organizer's] credentials of competency but also ensure automatic popular invitation".[54] The difficulty was that Daley's experience was such that that city hall could not be drawn into a sufficiently damaging confrontation. The mayor responded to the brutal reception for Freedom marchers in the white neighborhoods of Gage Park and Marquette Park with a judicious expression of sympathy and support. King balked at a further escalation—a march through the red-lined suburb of Cicero, "the Selma of the North"—and he allowed Daley to draw him into the negotiation of an open-housing deal[55] that was to prove toothless.[56] (After King's assassination, Alinsky argued that Woodlawn was the one black area of Chicago that did not "explode into racial violence" because, while their lives were not "idyllic", with TWO people "finally" had a sense of "power and achievement").[57]

At the end of the sixties Alinsky complained that student activists had been more interested in "revelation" than in "revolution," and that their campus politics was little more than street theater.[58] From the perspective of real social change, he regarded their outraging of middle-class sensibilities to have been a tactical mistake.[59]

Later life[edit]

"The myth of Saul Alinsky" criticism[edit]

In the summer of 1967, in an article in Dissent, Frank Riessman summarized a broader left-wing case against Alinsky. Seeking to explode "The Myth of Saul Alinsky", Riessman argued that rather than politicize an area, Alinsky's organizational efforts simply directed people "into a kind of dead-end local activism." Alinsky's opposition to large programs, broad goals, and ideology confused even those who participated in the local organizations because they find no context for their action. As a result, confined to what might be secured by purely local initiative, they achieved, at best, "a better ghetto."[60]

Riessman insisted that it was for the "organizer-strategist-intellectual" to "provide the connections, the larger view that will lead to the development of a movement," but adding—"this is not to suggest that the larger view should be imposed upon the local group." The New Left themselves seemed unable to strike the necessary balance. As they appeared to drift in events of the 1960s, failing above all to stop the war in Vietnam, Gitlin suggests that the SDS constructed their larger view "on the cheap".[61] Far from reconciling neighborhood agendas (welfare, rent, police harassment, garbage pick-up . . .) with radical ambition, their reheated revolutionary dogma prepared a "left exit" from community organizing, something that most New Left groups had effected by 1970.[62]

Alinsky's dismissal of Riessman as "a little whining Pekingese," as someone he "refused to debate with,"[63] might suggest that Alinsky was sensitive to the charge that the communities he helped organize were led into a political cul-de-sac. In 1964, he and Hoffman had agreed that The Woodlawn Organization was "stymied." It staggered in the face of deteriorating housing, chronic unemployment, and bad schools in a political environment that was unfriendly-to-hostile. Unless they did something, TWO "would go down." Alinsky was not a community-organizing purist. He saw the possibility of an electoral breakout: of Woodlawn helping mount a challenge to the incumbent in the 1966 Democratic-Party primary for the 2nd Congressional District. But Brazier, his preferred candidate, would not run and the community organization was fearful for its non-political tax-exempt status. In the end Daley's political machine had little difficulty in rolling over the additional support galvanized for the reform-minded state legislator, Abner Mikva.[64]

Playboy interview[edit]

It was a measure of his national celebrity that in March 1972, having "elevated the art of the magazine interview" with leaders such as Fidel Castro, Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X,[65] Playboy magazine published a 24,000-word interview with Alinsky.[66]

Alinsky was introduced as "a bespectacled, conservatively dressed community organizer who looks like an accountant and talks like a stevedore," a figure "hated and feared", according to The New York Times, "in high places from coast to coast", and acknowledged by William F. Buckley Jr., "a bitter ideological foe", as "very close to an organizational genius". Levelling against him the charges of the New Left, the interview effectively invited Alinsky to summarize the lessons he had drawn for the new generation of activists in (a revision of an earlier work) Rules for Radicals: A Pragmatic Primer for Realistic Radicals.

Life cycle of organizations[edit]

Alinsky was confronted with "the tendency" of communities he had helped organize to eventually "join the establishment in return for their piece of the economic action", Back of the Yards, "now one of the most vociferously segregationist areas of Chicago," being cited as a "case in point". For Alinsky, this was only a "challenge." It is "a recurring pattern": "Prosperity makes cowards of us all, and the Back of the Yards is no exception. They've entered the nightfall of their success, and their dreams of a better world have been replaced by nightmares of fear—fear of change, fear of losing their material goods, fear of blacks."

Alinsky explained that the life span of one of his organizations might be five years. After that it was either absorbed into administering programs (rather than building people power) or died. That was something that just had to be accepted, with the understanding that "discrimination and deprivation does not automatically endow [the have-nots] with any special qualities." Perhaps he would move back into the area to organize "a new movement to overthrow the one I built 25 years ago." Did he not find this process of co-optation discouraging? "No. It's the eternal problem." All life is a "relay race of revolutions", each bringing society "a little closer to the ultimate goal of real personal and social freedom."

But what were his "so-called" radical critics "in fact saying"? That when a community comes to him ("we're being shafted in every way") and ask for help, he should say, "sorry . . .if you get power and win, then you'll become, just like Back of the Yards, materialistic and all that, so just go on suffering, it is better for your souls"? "It's kind of like a starving man coming up to you and begging you for a loaf of bread, and your telling him, 'Don't you realize that man doesn't live by bread alone.' What a cop out."[67]

Revolutionary youth may have "few illusions about the system," but in Rules for Radicals Alinsky suggested "they have plenty of illusions about the way to change our world."[68] The "liberal cliché about reconciliation of opposing forces," so often invoked in opposition to radical confrontation, may be "a load of crap." "Reconciliation means just one thing: when one side gets enough power, then the other side gets reconciled to it." But opposition to consensus politics does not mean opposition to compromise — "just the opposite." "In the world as it is, no victory is ever absolute". "There is never nirvana." A "society without compromise is totalitarian."[69] And "in the world as it is, the right things also invariably get done for the wrong reasons."[70]

Organizing the middle class[edit]

For Alinsky, the real limitation of his organizing experience was that it had not extended into the middle-class majority:[71]

Christ, even if we could manage to organize all the exploited low-income groups – all the blacks, chicanos, Puerto Ricans, poor whites – and then, through some kind of organizational miracle, weld them all together into a viable coalition, what would you have? At the most optimistic estimate, 55,000,000 people by the end of this decade – but by then the total population will be over 225,000,000, of whom the overwhelming majority will be middle class. . . . Pragmatically, the only hope for genuine minority progress is to seek out allies within the majority and to organize that majority itself as part of a national movement for change.

The middle classes may be "conditioned to look for the safe and easy way, afraid to rock the boat," but Alinsky believed "they're beginning to realize the boat is sinking." On a wide range of issues, they feel "more defeated and lost today than the poor do." They were, Alinsky insisted, "good organizational material:" "more amorphous than some barrio in Southern California", so that "you're going to be organizing all across the country," but "the rules are the same."[71]

In 1968 he secured a year's funding in Chicago from the Midas International Corporation to train white middle class suburban activists. As understood by corporate president Gordon Sherman, the proposition was that "lack of organization in white neighborhoods can be as harmful to the total society as lack of organization in the black community. We all live in our own ghettos".[72] Alinsky, however, never predicted exactly what form or direction middle-class organization would take. In Horwitt's sympathetic view he was "too empirical for that." He did suggest that "the chance for organization for action on pollution, inflation, Vietnam, violence, race, taxes is all about us," making it clear that he envisaged organization based on a community of the interest rather than on the dubious neighborliness of the suburb.[73]

In 1969 in Chicago, Alinsky and his IAF trainees helped initiate a city-wide Campaign Against Pollution (later to become the Citizens Action Program to Stop the Crosstown—a billion-dollar expressway).[74] Alinsky was not beyond believing that such initiatives, scaled-up nationally, could "move on to the larger issues: pollution in the Pentagon and Congress and the board rooms of the megacorporations." Challenging, but the alternative, Alinsky warned, was for the "impotence" of the middle classes to turn into "political paranoia." This would make them "ripe for the plucking by some guy on horseback promising a return to the vanished verities of yesterday."[71]

Death and family[edit]

On June 12, 1972, three months after the publication of the Playboy interview, Alinsky died, aged 63, from a heart attack while walking near his home in Carmel, California.[22]

Alinsky's parents divorced when he was 18. He remained close to his mother, Farah Rice, who survived him. She acknowledged his national notoriety but not his politics. "As a Jewish mother, she begins where other Jewish mothers leave off. . . it was all anticlimatic after I got that college degree."[75]

Alinsky was married three times. His first wife, Helene Simon, whom he had met at the University of Chicago, drowned in 1947 while trying to save two children. Alinsky mourned her passing for many years.[76] His second marriage to Jean Graham was also to take a tragic turn. A diagnosis of multiple sclerosis proved to be the onset of serious mental health problems and led to her hospitalization. Alinsky ended the marriage after several years but maintained regular contact. In the year before his death, he married Irene McInnis. He had two children from his first marriage, Kathryn Wilson and Lee David Alinsky.[76][77]

Legacy[edit]

Industrial Areas Foundation[edit]

It has been suggested that "Alinsky is to community organizing as Freud is to analysis." Having written about it, "philosophized about it, and provided the first set of rules", he was the first to call attention to community organizing "as a distinct program, with a life and literature of its own, separate from any particular cause such as the union movement or Populism."[17] His biographer Sanford Horwitt credits Alinsky "more than anybody ... for demonstrating that community organizing could be a lifelong career."[78]

The Industrial Areas Foundation still claims to be "the nation's largest and longest-standing network of local faith and community-based organizations."[19] They report "victories" on, among other issues, housing and neighborhood revitalization, public transport and infrastructure, living-wage jobs and workforce development, support for local labor unions, criminal justice reform, and tackling the opioid crisis.[79]

When Alinsky died, Edward T. Chambers became the IAF's executive director. Hundreds of professional community and labor organizers and thousands of community and labor leaders have been trained at its workshops.[80] Fred Ross, who worked for Alinsky, was the principal mentor for Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta. Other organizations following in the tradition of the Congregation-based Community Organizing pioneered by IAF include PICO National Network, Gamaliel Foundation, Brooklyn Ecumenical Cooperatives, founded by former IAF trainer Richard Harmon, and Direct Action and Research Training Center (DART).[80][81] Such had been their role in the IAF and its projects that on his Firing Line television program William F. Buckley introduced Alinsky as "the pet revolutionary of the church people of America".[63]

People's Action[edit]

Chicago-based National People's Action (NPA), a federation of 29 community organizing groups in 18 U.S. states, consciously committed to Alinsky's bottom-up, door-to-door methodologies. It was co-founded in 1972 by Shel Trapp (1935–2010), who trained under Alinsky-trained organizer Tom Gaudet at the IAF.[82] NPA's successful national campaign to pass the Community Reinvestment Act CRA (1977) challenged the assertion that Alinsky-style organizing is only local and confined to winnable single-issue campaigns. In 2016, it coalesced with two other community-organizing networks to create People's Action and the People's Action [training] Institute, dedicated to building "the power of poor and working people, in rural, suburban, and urban areas, to win change" not only "through issue campaigns" but also, in clearer distinction to the IAF, through elections.[83]

Citizens UK and L'Institut Alinsky, France[edit]

In 1989, following trainee experience with the IAF in Chicago, in England Neil Jameson established the Citizens Organising Foundation. Now Citizens UK, it supports communities in several cities, and since 2001 has been associated with the high-profile campaign for a living wage.[84]

Drawing inspiration from both Citizens UK and the IAF, in 2012 Alinsky's community-organizing methods were tried in France leading to the creation in Grenoble of the Alliance Citoyenne (Citizens Alliance).[85] Similar initiatives followed in Rennes in 2014, in Aubervilliers, in Seine St Denis in 2016 and in the Lyon metropolitan area in 2019.[86]

In October 2017, the leaders of the Alliance Citoyenne and the researchers Julien Talpin and Hélène Balazard founded the Alinsky Institute,[87] a think tank and training organization to develop and promote methods of citizen empowerment in blue-collar and immigrant suburbs (banlieues) which, with the decline in the traditional parties of the left, have had little political voice.[88]

An assessment of Institute's work suggested that a critical problem for "Alinskysim" is the activists’ "need for recognition": "when they practice community organizing, the dozens of hours they devote to political struggle are in fact erased in favor of the inhabitants trained in mobilization".[89] More controversially, because of the alleged political partisanship, critics observe that the Alinsky Institute has trained leading activists in La France insoumise.[89]

In Germany in 1993, two of Alinsky's students and co-workers, Don Elmer (Center for Community Change, San Francisco) and Ed Shurna (Interfaith Organizing Project and Gamaliel Foundation, Chicago) initiated the first training courses in "Community Organizing" (CO), supported by several local projects.[90] Assisted by the Catholic University of Applied Social Sciences, the first community organization (Bürgerplattform) based on Alinsky's principles was established in a Berlin neighborhood in 2002.[91]

"Alinskyism"[edit]

Among political activists on the left, Alinsky’s legacy continues to be disputed. Cautions against looking to Alinsky for "a road map" to "rebuild power in the age of Trump" repeat the charge of the New Left: "'Alinskyism' — apolitical 'single-issue' campaigns that focus on 'winnable demands' run by a well-oiled, staff-heavy organization—shut the door to more democratic and transformational forms of working-class mobilization."[92] At the same time, Alinsky has been rediscovered and defended as an inspiration for the Occupy movement and the mobilization for climate action.[93] Activists for Extinction Rebellion (XR), founded in Britain, cite Rules for Radicals as a source of inspiration as to "how we mobilise to cope with emergency", and "strike a balance between disruption and creativity".[94] XR co-founder, Roger Hallam, has been clear that the strategy of public disruption is "heavily influenced" by Alinsky: "The essential element here is disruption. Without disruption, no one is going to give you their eyeballs".[95]

The Israeli journalist and pro-Settler activist David Bedein views Alinsky as a major influence on his work.[96]

In 2020, the Reuters Agency "fact check team" noted that viral images on social media were circulating quotes attributed to Rules for Radicals and Reveille for Radicals, which suggest that Alinsky set out eight fundamental rules for creating a "social state". The text in the images seems to equate this in turn with Soviet communism. The quotes attributed to Alinsky, however, were not found in his writings.[97]

Appropriation by the Tea Party movement[edit]

In the 2000s, Rules for Radicals did develop as a primer for middle-class mobilization, but it was of a kind and in a direction—the return to "vanished verities"—that Alinsky had feared. As did William F. Buckley in the 1960s, a new generation of libertarian, right-wing populist, and conservative activists seemed willing to admire Alinsky's disruptive organizing talents while rejecting his social-justice politics. Rules for Radicals, and adaptations of the book, began circulating among Republican Party Tea Party activists. According to spokesman Adam Brandon, the conservative non-profit organization FreedomWorks distributed a short adaptation of Alinsky's work, Rules for Patriots, through its entire network. Former Republican House Majority Leader Dick Armey is also reported to have given copies of Alinsky's book to leaders of the Tea Party movement.[98] In Rules for Conservative Radicals (2009) Michael Patrick Leahy, an early Tea Party leader, offered "sixteen rules for conservative radicals based on lessons from Saul Alinsky, the Tea Party Movement, and the Apostle Paul".[99]

Linked to Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama[edit]

Once it appeared that links could be drawn between Alinsky and two major Democratic-Party presidential hopefuls, Senator Hillary Clinton and Senator, later President, Barack Obama, conservatives were interested less in appropriating from the organizing tactician, than in profiling Alinsky as a far-left radical. Alinsky, it was discovered, had been the subject of then Hillary Rodham's senior college thesis.[59] Clinton had not been uncritical. Alinsky believed that community leaders who generate pressure on the system from the outside could produce more effective change than the lofty lever-pullers on the inside. But Clinton argued that suburbanization and a federal consolidation of power meant change needed to be achieved at levels that Alinsky's model was not designed to target. Nonetheless, her conclusion allowed that Alinsky "has been feared – just as Eugene Debs or Walt Whitman or Martin Luther King has been feared, because each embraced the most radical of political faiths — democracy."[100]

For three years, from June 1985 to May 1988, Obama was the director of the Developing Communities Project (DCP), a church-based community organization on Chicago's far South Side.[101][102] Alinsky biographer Sanford Horwitt, saw the influence of Alinsky's teaching not only on Obama's work in Chicago but also on his successful 2008 presidential run.[103] Yet Obama too commented on having seen "the limits of what can be achieved" at the community level. He also expressed the view that "Alinsky understated the degree to which people's hopes and dreams and their ideals and their values were just as important in organizing as people's self-interest." Sen. Dick Durbin (D-Ill.), a friend of Obama's, saw another difference. "If you read Alinsky's teachings, there are times he's confrontational. I have not seen that in Barack. He's always looking for ways to connect."[104]

Right-wing controversy[edit]

In his 1996 biography of her, The Seduction of Hillary Rodham, David Brock dubbed Hillary Clinton "Alinsky's daughter."[105] Barbara Olson began each chapter of her 1999 book on Clinton, Hell to Pay, with a quote from Alinsky, and argued that his strategic theories directly influenced her behavior during her husband's presidency.[106] In 1993, Clinton asked Wellesley College to seal her thesis on Alinsky for the duration of her husband's presidency.[107]

As his candidacy gained strength, and once he had defeated Clinton for the Democratic Party nomination, attention shifted to Obama's ties to Alinsky.[108][109] Monica Crowley, Bill O'Reilly, and Rush Limbaugh repeatedly drew a connection, with the latter asking, "Has [Obama] ever had an original idea — by that, I mean something not found in The Communist Manifesto? Has he? Has he simply had an idea not found in Saul Alinsky's Rules for Radicals?" Glenn Beck produced a four-part radio series to expose Alinsky's "vision for a Godless, centrally controlled utopia." In Barack Obama's Rules for Revolution: The Alinsky Model (2009) David Horowitz argued "the roots" of his administration's "effort to subject America to a wholesale transformation" were to be found in the teachings of "the guru of Sixties radicals"—an Alinsky admonition to be "flexible and opportunistic and say anything to get power."[110]

Epitaph[edit]

As an epitaph for Alinsky, his biographer Sanford Horwitt wrote:

Alinsky was a true believer in the possibilities of American democracy as a means to social justice. He saw it as a great political game among competing interests, a game in which there are few fixed boundaries and where the rules could be changed to help make losers into winners and vice versa. He loved to play the game...[111]

Publications[edit]

Articles[edit]

- Alinsky, Saul D. (1934). "A sociological technique in clinical criminology". Clinical Sociology Review. 1 (2 Article 5): 12-24.

- —— (1938). "The basis in the social sciences for social treatment of adult offenders". Federal Probation. 2 (October): 21-31.

- —— (1941). "Community analysis and organization". American Journal of Sociology. 46 (6): 797-808. doi:10.1086/218794. S2CID 10074559.

- —— (1942). "Youth and morale". American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 12 (4): 598-602. doi:10.1111/j.1939-0025.1942.tb05954.x.

- —— (1965). "The war on poverty-political pornography". Journal of Social Issues. 21 (1): 41-47. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.1965.tb00482.x.

- Alinsky, S.D. (1967). "The poor and the powerful". Psychiatric Research Reports. 21: 22–28. PMID 6053466.

- Alinsky, Saul D. (1984). "Community analysis and organizations". Clinical Sociology Review. 2 (1 Article 6): 25-34.

Books[edit]

- Alinsky, Saul D. (1946). Reveille for radicals (PDF). Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press.

- Alinsky, Saul (1949). John L. Lewis: An unauthorized biography. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons.

- Alinsky, Saul D. (1971). Rules for Radicals A Practical Primer for Realistic Radicals (PDF). New York: Random House.

- Doering, Bernard E., ed. (1994). The Philosopher and the Provocateur: The Correspondence of Jacques Maritain and Saul Alinsky. Notre Dame, Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press.

See also[edit]

- Community development

- Community education

- Community practice

- Community psychology

- Critical consciousness

- Critical psychology

- Organization workshop

References[edit]

- ^ "Saul David Alinsky". Dictionary of American Biography. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. 1994. Gale Document Number: BT2310018941. Retrieved September 7, 2011 – via Fairfax County Public Library.(subscription required) Gale Biography in Context.

- ^ "Saul David Alinsky Collection". Hartford, Connecticut: The Watkinson Library, Trinity College. Archived from the original on March 21, 2012. Retrieved September 7, 2011.

- ^ Brooks, David (March 4, 2010). "The Wal-Mart Hippies". The New York Times. Retrieved September 8, 2010.

Dick Armey, one of the spokesmen for the Tea Party movement, recently praised the methods of Saul Alinsky, the leading tactician of the New Left.

- ^ Fowle, Farnsworth (June 13, 1972). "A Local Agitator". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 17, 2023.

- ^ Horwitt (1989), p. 3.

- ^ Von Hoffman, Nicholas (2010). Radical: A Portrait of Saul Alinsky. Nation Books. pp. 108–109. ISBN 978-1-56858-625-0.

He passed the word in the Back of the Yards that this Jewish agnostic was okay, which at least ensured that he would not be kicked out the door.

- ^ Curran, Charles E. (2011). The Social Mission of the U.S. Catholic Church: A Theological Perspective. Georgetown University Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-1-58901-743-6.

Saul D. Alinsky, an agnostic Jew, organized the Back of the Yards neighborhood in Chicago in the late 1930s and started the Industrial Areas Foundation in 1940 to promote community organizations and to train community organizers.

- ^ Hudson, Deal Wyatt (1987). Hudson, Deal Wyatt; Mancini, Matthew J. (eds.). Understanding Maritain: Philosopher and Friend. Mercer University Press. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-86554-279-2.

Saul Alinsky was an agnostic Jew for whom religion of any kind held very little importance and just as little relation to the focus of his life's work: the struggle for economic and social justice, for human dignity and human rights, and for the alleviation of the sufferings of the poor and downtrodden.

- ^ a b Norden (1972), p. 62.

- ^ Horwitt (1989), pp. 11–13.

- ^ a b c d Sanders, Marion K (1965). The Professional Radical: Conversations with Saul Alinsky (PDF). New York: Harper and Row. pp. 19–21, 26–27. Retrieved December 9, 2020.

- ^ Norden (1972), pp. 62–64.

- ^ Alinsky, Saul (2007) [1949]. John L. Lewis: An Unauthorized Biography. Whitefish, Montana: Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 978-1-43259-217-2.

- ^ Norden (1972), p. 71.

- ^ Horwitt (1989), pp. 199–20.

- ^ Norden (1972), pp. 71–72.

- ^ a b Slayton, Robert A. (1996). "Review of Let Them Call Me Rebel: Saul Alinsky, His Life and Legacy". Chapman University Digital Commons. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ^ Horwitt (1989), p. 105.

- ^ a b "Who We Are". Industrial Areas Foundation. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ^ Putnam, Robert (2000). Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-74320-304-3.

- ^ Horwitt (1989), p. 105

- ^ a b Fowle, Farnsworth (June 13, 1972). "Saul Alinsky, 63, Poverty Fighter and Social Organizer is Dead". New York Times. p. 46. Retrieved January 9, 2022.

- ^ Norden (1972), pp. 59–60.

- ^ Horwitt (1989), pp. 263–265.

- ^ Horwitt (1989), pp. 367–368.

- ^ Brazier, Arthur M. (1969). Black Self-Determination: The Story of the Woodlawn Organization. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co.

- ^ Slayton (1998)

- ^ Norden (1972), p. 169.

- ^ Norden (1972), p. 39.

- ^ Horwitt (1989), p. 493.

- ^ Norden (1972), pp. 173, 176–177.

- ^ Goodman, James; Sharp, Brian (July 20, 2014). "Riots spawned FIGHT, other community efforts". Democrat and Chronicle. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ^ Horwitt (1989).

- ^ Capp, Glenn R. (1967). The Great Society A Sourcebook of Speeches. Belmont, CA: Dickenson Publishing Company, Inc. pp. 164–174.

- ^ a b Alinsky, Saul (1965). "The War on Poverty--Political Pornography". The Journal of Social Issues. 22 (1): 41–47. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.1965.tb00482.x.

- ^ Davidson, Roger (1969). "The War on Poverty: Experiment in Federalism". The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 385 (Evaluating the War on Poverty): 1–13. doi:10.1177/000271626938500102. JSTOR 1037532. S2CID 154640268.

- ^ Horwitt (1989), p. 48.

- ^ Kifner, John (January 15, 1967). "Saul D. Alinsky; A Professional Radical Rallies the Poor". timesmachine.nytimes.com. Retrieved January 9, 2022.

- ^ Horwitt (1989), pp. 240–24.

- ^ a b Horwitt (1989), p. 24.

- ^ a b Alinsky, Saul (1945). Reveille for Radicals (PDF). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 16, 24. Retrieved December 9, 2020.

- ^ Norden (1972), p. 79.

- ^ Matthews, Dylan (July 19, 2016). "Who is Saul Alinsky, and why does the right hate him so much?". Vox. Retrieved December 9, 2020.

- ^ "Stokely Carmichael". History.com. 2009. Retrieved April 2, 2023.

- ^ Hamilton, Charles V.; Ture, Kwame (2011) [First published]. Black Power: Politics of Liberation in America. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-307-79527-4.

- ^ Horwitt (1989), p. 508.

- ^ Horwitt (1989), p. 509.

- ^ Horwitt (1989), p. 533.

- ^ a b Students for a Democratic Society (1962). "The Port Huron Statement". Retrieved January 21, 2020 – via The Sixties Project.

- ^ Sale, Kirkpatrick (1973). SDS: The Rise and Development of The Students for a Democratic Society (PDF). New York: Vintage Books. pp. 86–87 – via Libcom.org.

- ^ Horwitt (1989), p. 525.

- ^ Sonnie & Tracy (2011), p. 33.

- ^ Sonnie & Tracy (2011), p. 44.

- ^ Alinsky (1971), p. 100.

- ^ Ralph, James R. (1993). Northern Protest: Martin Luther King Jr., Chicago, and the Civil Rights Movement. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-67462-687-4.

- ^ Royko, Mike (1971). Boss: Richard J. Daley of Chicago. New York: New American Library. p. 158.

- ^ Norden (1972), p. 176.

- ^ Horwitt (1989), p. 528.

- ^ a b Dedman, Bill (March 2, 2007). "Reading Hillary Rodham's hidden thesis". NBC News. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ^ Riessman, Frank (July 1967). "More on Poverty: The Myth of Saul Alinsky" (PDF). Dissent. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ^ Gitlin, Todd (2003). The Whole World Is Watching: Mass Media in the Making & Unmaking of the New Left. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. p. 179. ISBN 978-0-52023-932-6.

- ^ McDowell, Manfred (2013). "A Step into America: The New Left Organizes the Neighborhood". New Politics. Vol. XIV, no. 2. pp. 133–141. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ^ a b Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "Mobilizing the Poor". Firing Line with William F. Buckley Jr. Season 2. Episode 79. December 11, 1967. PBS. Retrieved January 21, 2020 – via YouTube.

- ^ Horwitt (1989), pp. 313–315.

- ^ Italie, Hillel (2017). "From MLK to John Lennon: How Playboy elevated the art of the magazine interview". Global News. Associated Press. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ^ Norden (1972).

- ^ Norden (1972), pp. 76–78.

- ^ Alinsky (1971), p. xiii.

- ^ Alinsky (1971), p. 59.

- ^ Norden (1972), p. 170.

- ^ a b c Norden (1972), p. 60.

- ^ Janson, Donald (August 7, 1968). "Alinsky to Train White Militants" (PDF). New York Times. p. 27. Retrieved January 8, 2022.

- ^ Horwitt (1989), p. 534.

- ^ Horwitt (1989), pp. 531–532.

- ^ Norden (1972), p. 63.

- ^ a b von Hoffman, Nicholas (June 29, 2010). Radical: A Portrait of Saul Alinsky. New York: PublicAffairs. ISBN 978-1-56858-625-0.

- ^ Fowle, Farnsworth (June 13, 1972). "A Local Agitator". The New York Times. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ^ Horwitt (1989), p. 544.

- ^ "Impact Report 2018" (PDF). IAF. Retrieved November 22, 2019.

- ^ a b Meister, Dick. "Labor – And A Whole Lot More: A Trailblazing Organizer's Organizer". Archived from the original on October 21, 2004.

- ^ Siegel, Robert; Horwitt, Sanford (May 21, 2007). "NPR Democrats and the Legacy of Activist Saul Alinsky". All Things Considered. NPR. Retrieved September 8, 2011.

Robert Siegel talks to author Sanford Horwitt, who wrote a biography of Saul Alinsky called Let Them Call Me 'Rebel'. The book traces Alinsky's early activism in Chicago's meatpacking neighborhood.

- ^ Ramirez, Margaret (October 25, 2010). "Shel Trapp, 1935–2010, community organizer, co-founder of National People's Action". Chicago Tribune.

- ^ "The People's Platform 2020" (PDF). People's Action. Retrieved November 22, 2019.

- ^ Jameson, Neil (March 24, 2010). "People can play their part in the governance of the nation". the Guardian. Retrieved March 17, 2021.

- ^ "Community organizing : pourquoi il faut oublier Saul Alinsky - Organisez-vous !" (in French). February 26, 2019. Retrieved March 21, 2021.

- ^ à 13h37, Par Quentin Laurent Le 22 novembre 2017 (November 22, 2017). "La France insoumise à l'assaut des quartiers populaires". leparisien.fr (in French). Retrieved March 17, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Qui sommes-nous ?". Institut Alinsky (in French). Retrieved March 17, 2021.

- ^ Talpin, Julien (June 22, 2017). "What's the matter with the banlieues? Exploring the importation of the American community organizing tradition by French social movements". Metropolitics.

- ^ a b Saint-André, Elsa de La Roche. "LFI, Nupes : qu'est-ce que l'institut Alinsky, qui forme des militants à «aller chercher les colères»?". Libération (in French). Retrieved August 22, 2022.

- ^ "Wegweiser Bürgergesellschaft: Zur Geschichte des Community Organizing in Deutschland". www.buergergesellschaft.de. Retrieved March 21, 2021.

- ^ Renner, Gesela (2015). "Vielfalt in der Bürgerbeteiligung: Das Beispiel "Community Organizing"". Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung - Gutvertreten (in German). Retrieved March 21, 2021.

- ^ Petcoff, Aaron (May 10, 2017). "The Problem With Saul Alinsky". Jacobin. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ^ Miller, Mike (May 23, 2014). "Building Organization Through Movements: A Defense of Alinsky". Dissent. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ^ Mackay, Donna (October 22, 2019). "The books that inspired the Extinction Rebellion protesters". Penguin Random House. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ^ Davies, Caroline (April 19, 2019). "Extinction Rebellion and Attenborough put climate in spotlight". The Guardian. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ^ Bedein, David (June 25, 2012). "Alinksy's ideas can help Israel, too". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved February 20, 2021.

- ^ "False claim: Saul Alinsky listed a scheme for world conquest, creation of the "social state"". Reuters. April 23, 2020. Retrieved February 20, 2021.

- ^ Williamson, Elizabeth (January 23, 2012). "Two Ways to Play the 'Alinsky' Card". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved January 26, 2011.

- ^ Leahy, Michael Patrick (2009). Rules for Conservative Radicals: Lessons from Saul Alinsky, the Tea Party Movement, and the Apostle Paul in the Age of Collaborative Technologies. Nashville, Tennessee: C-Rad Press. ISBN 978-0-97949-744-5.

- ^ Rodham (1969), p.74.

- ^ Secter, Bob; McCormick, John (March 30, 2007). "Portrait of a pragmatist". Chicago Tribune. p. 1. Archived from the original on December 14, 2009. Retrieved February 14, 2009.

- ^ Lizza, Ryan (March 19, 2007). "The Agitator; Barack Obama's unlikely political education". The New Republic. Retrieved July 16, 2008.

- ^ Cohen, Alex; Horwitt, Sanford (January 30, 2009). "Saul Alinsky, The Man Who Inspired Obama". Day to Day. NPR. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

About his book Let Them Call Me Rebel: Saul Alinsky His Life and Legacy

- ^ Slevin, Peter (March 25, 2007). "For Clinton and Obama, a Common Ideological Touchstone". The Washington Post. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ^ Brock, David (1998). The Seduction of Hillary Rodham. New York: Free Press. ISBN 978-0-68483-770-3.

- ^ Olson, Barbara (1999). Hell to Pay: The Unfolding Story of Hillary Rodham Clinton. Washington, DC: Regnery Publishing. ISBN 978-0-89526-274-5.

- ^ Dedman, Bill (March 2, 2007). "How the Clintons wrapped up Hillary's thesis". NBC News. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ^ Sugrue, Thomas J. (2012). "Saul Alinsky: The activist who terrifies the right". Salon. Retrieved April 2, 2023.

- ^ Matthews, Dylan (October 6, 2014). "Who is Saul Alinsky, and why does the right hate him so much?". Vox. Retrieved April 2, 2023.

- ^ Horowitz, David (2009). Barack Obama's Rules for Revolution: The Alinsky Model. Sherman Oaks, California: David Horowitz Freedom Center. ISBN 978-1-88644-268-9.

- ^ Horwitt (1989), p. xvi.

Bibliography[edit]

- Horwitt, Sanford D. (1989). Let Them Call Me Rebel: Saul Alinsky, his life and legacy. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0-394-57243-2.

- Norden, Eric (1972). "Playboy Interview: Saul Alinsky. A Candid Conversation with the Feisty Radical Organizer". Playboy. No. 3. pp. 59–78, 150, 169–179. ISSN 0032-1478. Archived from the original on July 31, 2020.

Further reading[edit]

Articles[edit]

- Riessman, Frank (1967). "The myth of Saul Alinsky" (PDF). Dissent. 14 (4 (July-August)): 469-478.

- Billson, Janet Mancini (1984). "Saul Alinsky: The contributions of a pioneer clinical sociologist". Clinical Sociology Review. 2 ((1 Article 4)): 7-11.

- Glass, John F. (1984). "Saul Alinsky in retrospect". Clinical Sociology Review. 2 (1 (Article 7)): 35-38.

- Engel, Lawrence J. (2002). "Saul D. Alinsky and the Chicago school" (PDF). The Journal of Speculative Philosophy. 16 (1): 50-66. doi:10.1353/jsp.2002.0002. S2CID 144654916.

- Phulwani, Vijay (2016). "The Poor Man's Machiavelli: Saul Alinsky and the Morality of Power". American Political Science Review. 110 (4): 863-875. doi:10.1017/S0003055416000459. S2CID 151625729 – via Academia.edu.

- Giorg, Simona; Bartunek, Jean M.; King, Brayden G. (2017). "A Saul Alinsky primer for the 21st century: The roles of cultural competence and cultural brokerage in fostering mobilization in support of change". Research in Organizational Behavior. 37: 125-142. doi:10.1016/j.riob.2017.09.002 – via Academia.edu.

Books[edit]

- Sanders, Marion K. (1970). The professional radical: Conversations with Saul Alinsky. New York: Harper & Row.

- Finks, P. David (1984). The radical vision of Saul Alinsky. New York: Paulist Press.

- Knoepfle, Peg, ed. (1990). After Alinsky: Community organizing in Illinois. Springfield, Illinois: Sangamon State University.

- von Hoffman, Nicholas (2010). Radical: A portrait of Saul Alinsky. New York: Nation Books.

- Schutz, Aaron; Miller, Mike, eds. (2015). People power: The Saul Alinsky tradition of community organizing. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press. ISBN 978-0-8265-2041-8.

- Wise, Richard W. (2020). Redlined: A novel of Boston. Brunswick House Press. ISBN 978-0-9728-2233-6.

External links[edit]

- Democratic Promise, a documentary about Alinsky and his legacy

- Encounter with Saul Alinsky, Part 1: CYC Toronto, National Film Board of Canada documentary

- Encounter with Saul Alinsky, Part 2: Rama Indian Reserve, Archived September 12, 2018, at the Wayback Machine National Film Board of Canada documentary

- Saul Alinksy Went to War, Archived September 12, 2018, at the Wayback Machine National Film Board of Canada documentary

- Saul Alinsky, The qualities of an organizer (1971)

- Santow, Mark Edward (January 1, 2000). Saul Alinsky and the dilemmas of race in the post-war city (DPhil). University of Pennsylvania.

- Saul Alinsky's FBI files on the Internet Archive

- 1909 births

- 1972 deaths

- 20th-century American male writers

- Activists from California

- Activists from Chicago

- American anti-fascists

- American agnostics

- American democracy activists

- American environmentalists

- American feminists

- American male non-fiction writers

- American people of Russian-Jewish descent

- American political activists

- American political philosophers

- American anti-poverty advocates

- American anti-war activists

- Consequentialists

- Ecofeminists

- Jewish agnostics

- Jewish American community activists

- American community activists

- Jewish American non-fiction writers

- Jewish philosophers

- Liberalism in the United States

- Left-wing politics in the United States

- American male feminists

- New Left

- People from Carmel-by-the-Sea, California

- University of Chicago alumni

- Writers from Chicago