War of the Quadruple Alliance

| War of the Quadruple Alliance | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Anglo-Spanish Wars and Franco-Spanish Wars | |||||||||

The Battle of Cape Passaro, 11 August 1718, Richard Paton | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

Quadruple Alliance |

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

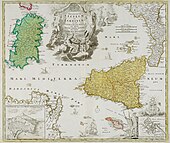

The War of the Quadruple Alliance [a] was fought from 1718 to 1720 by Spain, and the Quadruple Alliance, a coalition between Britain, France, Austria, and the Dutch Republic.[b] Caused by Spanish attempts to recover territories in Italy ceded in the 1713 Peace of Utrecht, most of the fighting took place in Sicily and Spain, with minor engagements in North America and Northern Europe. Spain also supported the Jacobite rising of 1719 in Scotland in an effort to divert British naval resources.

Spain recaptured Sardinia in 1717 from Habsburg Austria, followed by a landing in Sicily in July 1718. On 2 August, the Quadruple Alliance was formed and on 11th, the Royal Navy defeated a Spanish fleet at Cape Passaro. This meant their troops in Sicily could not be resupplied or reinforced, and Austrian land forces eventually retook the island. In October 1719, a British naval force sacked the Spanish port of Vigo.

The 1720 Treaty of The Hague restored the position prior to 1717, but with Savoy and Austria exchanging Sardinia and Sicily.

Background[edit]

Under the 1713 Peace of Utrecht that ended the War of the Spanish Succession, Spain ceded possessions in Italy and Flanders to Austria, and Sicily to Savoy. Their recovery was a priority for the French-born Philip V of Spain.[c][1] This objective was reinforced by chief minister Cardinal Alberoni, who like Philip's second wife Elisabeth Farnese was a native of Parma.[2]

Utrecht specified Spain could never be unified with either France or Austria, and under its terms Philip gave up any future claim to the French throne. However, a series of deaths in the French royal family between 1713 and 1715 made him heir presumptive to the five year old Louis XV, and he now cast doubts on this renunciation. Emperor Charles VI also refused to accept this principle, as well as delaying implementation of the Barrier Treaty in the newly acquired Austrian Netherlands, an objective for which the Dutch Republic had effectively bankrupted themselves. Concerned by these moves, Britain and France agreed the 1716 Anglo-French alliance to enforce these terms, then formed the Triple Alliance with the Dutch in January 1717.[3]

Its key principles were to ensure Charles and Philip reconfirmed the withdrawal of their claims to the thrones of Spain and France. In return for this, Savoy and Austria would exchange Sicily and Sardinia. Spain saw little benefit in this and decided to seize the opportunity to recover territorial losses agreed at Utrecht. As neither Savoy nor Austria possessed significant navies, the most obvious targets were the islands of Sardinia and Sicily, an ambition that aligned with the Italian dynastic claims of Elizabeth Farnese.[4]

In August 1717, Spanish forces landed on Sardinia and by November had re-established control of the island. They met little opposition; Austria was engaged in the 1716–1718 Austro-Turkish War, while France and the Netherlands needed peace to rebuild their shattered economies.[5] Attempts to resolve the situation through diplomacy failed and in June 1718, a British naval force arrived in the Western Mediterranean as a preventive measure.[6] Emboldened by their success in Sardinia, in July 1718 the Spanish landed 30,000 men on Sicily but the strategic position had now changed. Austria signed the July 1718 Treaty of Passarowitz with the Ottoman Empire, and on 2 August, joined Britain, France, and the Dutch in the Quadruple Alliance, which gave its name to the war that followed.[7]

War[edit]

Outbreak[edit]

The Spanish took Palermo on 7 July, then divided their army; on 18 July, Marquess of Lede opened the siege of Messina, while the duke of Montemar occupied the rest of the island. On 11 August, a British squadron commanded by Sir George Byng eliminated the Spanish fleet at the Battle of Cape Passaro. This was followed in the autumn by the landing of a small Austrian army, assembled in Naples by the Austrian Viceroy Count Wirich Philipp von Daun, near Messina to lift the siege by the Spanish forces. The Austrians were defeated in the First Battle of Milazzo on 15 October, and only held a small bridgehead around Milazzo.

In 1718, Cardinal Alberoni began plotting to replace the Duc d'Orléans, regent to the 5-year-old King Louis XV of France, with Philip V. This plot became known as the Cellamare conspiracy. After the plot was discovered, Alberoni was expelled from France, which declared war on Spain. By 17 December 1718, the French, British, and Austrians had all officially entered the war against Spain. The Dutch would join them later, in August 1719.

San Sebastián[edit]

The Duc d'Orléans ordered a French army under the Duke of Berwick to invade the western Basque districts of Spain in April 1719, still under the shock of Philip V's military intervention against them. Berwick successfully besieged San Sebastián and also entered northern Catalonia. In both regions there was support for the invaders from leading local figures, some of whom lobbied for them to be permanently annexed by France.[8] Spain attempted to counter this by launching its own expedition to Brittany, in the hope of raising a rebellion against the Regent of France. It consisted of a 1,000 troops, but carried arms for 10,000 more. However, after landing at Vannes they found little support amongst the inhabitants and withdrew.[9]

Sicily[edit]

In Sicily, the Austrians started a new offensive under Count Claude Florimond de Mercy. They first suffered a defeat in the Battle of Francavilla (20 June 1719). But the Spanish were cut off from their homeland by the British fleet and it was just a matter of time before their resistance would crumble. Mercy was then victorious in the second Battle of Milazzo, took Messina in October and besieged Palermo.

Invasion of Britain[edit]

In early 1719 the Irish exile, the Duke of Ormonde, organized an expedition with extensive Spanish support to invade Britain and replace King George I with James Stuart, the Jacobite "Old Pretender". However, his fleet was dispersed by a storm near Galicia in March 1719, and never reached Britain. A small force of 300 Spanish marines under George Keith, 10th Earl Marischal did land near Eilean Donan, but they and the Highlanders who supported them were defeated at the Battle of Eilean Donan in May 1719 and the Battle of Glen Shiel a month later, and the hopes of an uprising soon fizzled out.

Vigo[edit]

In retaliation for this attack, the British government prepared to launch a raid on the Spanish coast. An expedition was assembled at Portsmouth and the Isle of Wight under the command of Lord Cobham and George Wade.[10] They successfully captured Vigo and marched inland seizing the towns of Redondela and Pontevedra in October 1719. This caused some shock to the Spanish authorities as they realized how vulnerable they were to Allied amphibious attacks, with the potential to open up a new front away from the French frontier.

North America[edit]

The French captured the Spanish settlement of Pensacola in Florida in May 1719, pre-empting a Spanish attack on South Carolina. While Spanish forces retook the town in August 1719, it fell to the French again towards the end of the year and they destroyed the town before withdrawing.

In February 1720 a 1,200 strong Spanish force set out from Cuba to take the British settlement of Nassau in the Bahamas. After taking a large amount of plunder they were eventually driven off by the local militia.

Peace[edit]

Displeased with his kingdom's military performance, Philip dismissed Alberoni in December 1719, and made peace with the allies with the Treaty of The Hague on 17 February 1720.

In the treaty, Philip was forced to relinquish all territory captured in the war. However, his third surviving son's right to the Duchy of Parma and Piacenza after the death of Elisabeth's childless uncle, Antonio Farnese, was recognized.

France returned Pensacola and the remaining conquests in the north of Spain in exchange for commercial benefits. Included in the terms of this treaty, Victor Amadeus was forced to exchange Sicily for that of the less important Kingdom of Sardinia.

Legacy[edit]

The war provided a unique example during the eighteenth century when Britain and France were on the same side. It came during a period between 1716 and 1731 when the two countries were allies. Spain would later join with France in the Bourbon Compact, and the two would become enemies of the British once more. Spain later regained the Kingdom of Naples during the 1733 to 1735 War of the Polish Succession.[11]

See also[edit]

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ Dutch: Oorlog van de Quadruple Alliantie, French: Guerre de la Quadruple-Alliance, German: Krieg der Quadrupelallianz, Italian: Guerra della Quadruplice Alleanza

- ^ Not to be confused with the Quadruple Alliance (1815)

- ^ Formerly Philip of Anjou, and a member of the French House of Bourbon

References[edit]

- ^ Storrs, Ronald (2 December 2016). "The Spanish Monarchy in the Mediterranean Theater". Yale University Blog. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- ^ Solano 2011, pp. 237–238.

- ^ Lesaffer, Randall. "The 18th-century Antecedents of the Concert of Europe I: The Triple Alliance of 1717". Oxford Public International Law. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- ^ Lesaffer, Randall. "The 18th-century Antecedents of the Concert of Europe I: The Quadruple Alliance of 1718". Oxford Public International Law. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- ^ Szechi 1994, pp. 93–95.

- ^ Simms 2007, p. 135.

- ^ Tucker 2009, p. 724.

- ^ Oates 2019, p. 140.

- ^ Oates 2019, p. 142.

- ^ Oates pp. 143–144

- ^ Dhondt 2017, pp. 97–130.

Sources[edit]

- Dhondt, Frederik (2017). "Arrestez et pillez contre toute sorte de droit': Trade and the War of the Quadruple Alliance (1718–1720)" (PDF). Legatio: The Journal for Renaissance and Early Modern Diplomatic Studies. 1.

- Lesaffer, Randall. "The 18th-century Antecedents of the Concert of Europe I: The Triple Alliance of 1717". Oxford Public International Law.

- Lesaffer, Randall. "The 18th-century Antecedents of the Concert of Europe I: The Quadruple Alliance of 1718". Oxford Public International Law.

- Oates, Jonathon D (2019). The Last Armada: Britain and the War of the Quadruple Alliance, 1718–1720. Helion and Company.

- Simms, Brendan (2007). Three Victories and a Defeat: The Rise and Fall of the First British Empire, 1714–1783. Penguin. ISBN 978-0140289848.

- Solano, Ana Crespa (2011). Rommelse, Gijs; Onnekink, David (eds.). A Change of Ideology in Imperial Spain? in Ideology and Foreign Policy in Early Modern Europe (1650–1750). Routledge. ISBN 978-1409419136.

- Storrs, Ronald (2 December 2016). "The Spanish Monarchy in the Mediterranean Theater". Yale University Blog. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- Szechi, Daniel (1994). The Jacobites: Britain and Europe, 1688–1788. Manchester University Press. ISBN 0719037743.

- Tucker, Spencer, C (2009). A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East 6V: A Global Chronology of Conflict [6 volumes]: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1851096671.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Wars involving the Habsburg monarchy

- Wars involving France

- Wars involving Great Britain

- Wars involving the Holy Roman Empire

- Wars involving Spain

- Wars involving the Dutch Republic

- Wars involving the Netherlands

- 18th-century conflicts

- Conflicts in 1718

- Conflicts in 1719

- Conflicts in 1720

- 18th century in Austria

- 1718 in Europe

- 1719 in Europe

- 1720 in Europe

- Wars fought in Texas

- Wars of succession involving the states and peoples of North America

- Wars of succession involving the states and peoples of Europe

- War of the Quadruple Alliance